Can you trust images on social media?

Can you trust images on social media? The short answer is no.

Generative AI and the creation of deepfakes have made it difficult to distinguish between real and AI-generated images.

According to ethicist Martin Bekker,

The problem is simple: it’s hard to know whether a photo’s real or not anymore. Photo manipulation tools are so good, so common and easy to use, that a picture’s truthfulness is no longer guaranteed. (Bekker, 2025).

There are several reasons images are untrustworthy. These include deepfakes, manipulation and filtering, misleading context, and curated perceptions.

Curated perceptions are when a photographer presents an idealised reality of a situation, like an altered selfie.

A photographer can present an image in a misleading context, distorting the true meaning of a situation. It can be selective omissions.

Manipulation and filtering can include adjusting brightness, contrast, colour balance or saturation as well as a host of other adjustments.

According to the Victorian Police, deepfakes are realistic fake photos, videos and audio of real people that often appear online. They trick users into thinking that what they are seeing or hearing is true. In many situations, they are illegal. (Victoria Police 2025)

Why do we believe what we see?

Journalist Kalev Leetaru argues that the rise of deepfakes and the like is based on ‘seeing is believing’. He argues:

So long as there is an image or video clip associated with an event, we somehow believe it as if we ourselves witnessed it. We see visual materials as neutral and immune to human bias.

In reality, photographs and videos do not capture reality, they merely construct it. By aiming the camera one way instead of another, we tell only part of the story and consciously or subconsciously focus on details that confirm our narrative and exclude those that conflict with it. (Leetaru 2019)

AI Gen

Manipulation of images

Press photography is a type of historical image, and it is an area where ethics and the need to tell a story clash. The tension in this situation revolves around the preservation of the truth and modern enhancement.

The United States Press Association argues that

the camera lens is a tool for truth. The manipulation of images to serve narratives undermines not only the credibility of the individual, but also the reputation of the entire profession in society. With the advancement of digital technology, the responsibility to comply with ethical standards grows even more. (USPA 2025)

The distortion of the historical record is not new.

According to Alison Wishart

Hurley was simply following a practice in photography which dates back to American Civil War photographer George Barnard. (Wishart 2017)

The fundamental ethical principles regarding historical images include integrity and accuracy, transparency, and accountability.

Manipulation of historical photographs in the past was the erasure of the truth, where the visual evidence of the moment was removed to avoid offence.

Manipulation of images is not new

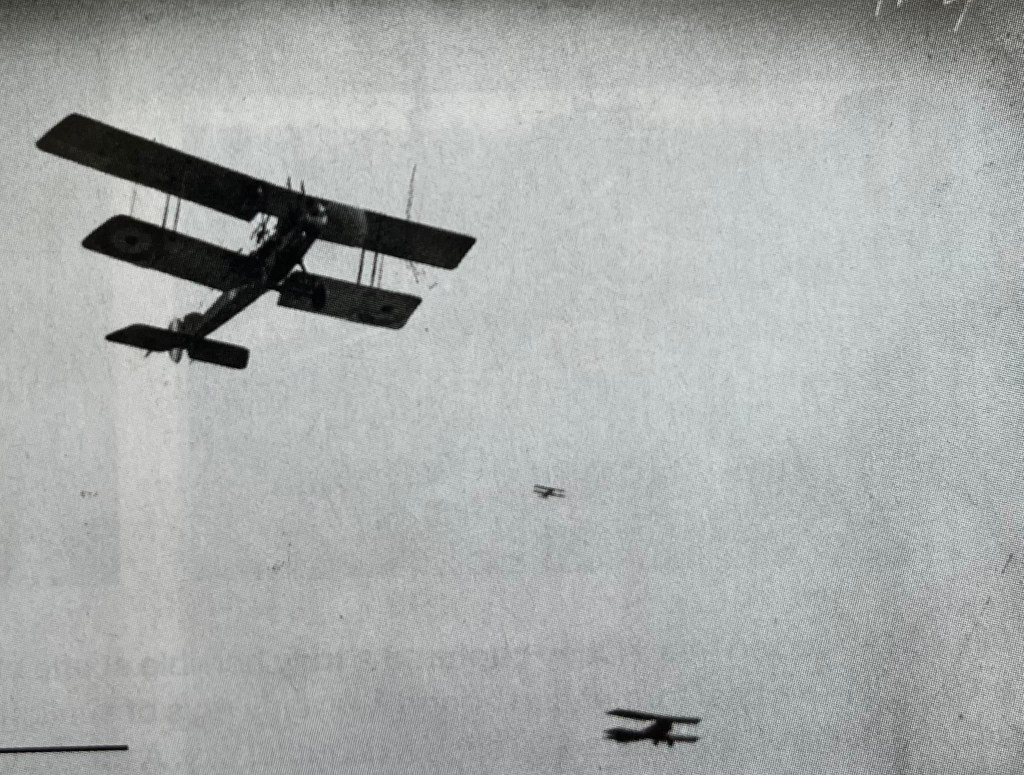

Famously Australian war photographer Frank Hurley manipulated his images of World War I to provide the public with graphic portrayals of the war’s horrors. He clashed with war correspondent and historian Charles Bean over the issue. (Wishart 2017)

Bean’s disagreement with Hurley got nasty. Charles Bean was adamant that Hurley’s composite photographs were lies and that history demanded the simple truth.

Hurley threatened to resign, and only General Birdwood’s intervention brokered a compromise. (Scott 2023)

Australian film producer Damien Parer has stated Bean branded Hurley’s photographs as fakes and demanded that he stop. (Parer 2026)

According to State Library historian Alison Wishart, Hurley’s position on the issue of photograph manipulation was that

war was conducted on a vast scale, it was impossible to capture the essence of it in a single negative. (Wishart 2017)

Hurley made a collage or composite of several photographic prints and called it ‘photographic impression pictures’, where a number of negatives were combined to produce a realistic impression of certain events. (Wishart 2017)

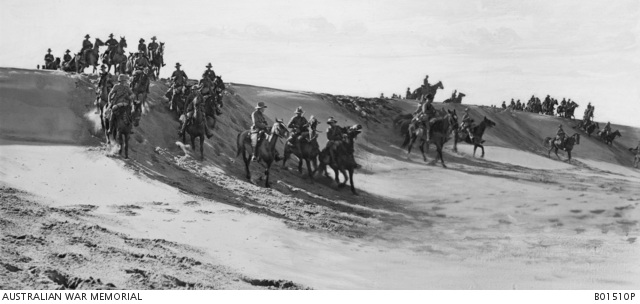

Former RAAF officer Rod Hutchings states that Hurley staged events after the battle to create a realistic scene. One such image where he reconstructed events was a photograph in 1918

near Esdud in Palestine, shows men of the 1st Australian Light Horse Brigade riding over the sandhills. (Hutchings 2026)

Author Scott Bennett maintains that Hurley’s 1917 photograph, ‘Over the Top,’ is justified. Scott states

Hurley felt compelled to use composite images as he saw it as his duty to portray the true horrors of war.

The photograph ‘Over The Top’ is a composite of 12 negatives. (Bennett 2023)

Solution to these problems

The solution to these issues is an ethical question: ‘What is the right thing to do?’.

Martin Bekker proposes two solutions: first, declare that photo manipulation has occurred, and second, disclose the type of photo manipulation carried out. (Bekker 2025)

Bekker argues that these solutions are straightforward. In the declaration ‘EA’ or ‘enhancement acknowledgement’. The disclosure should explain how the image was manipulated, e.g., by describing the changes or stating that Generative AI was used. (Bekker 2025)

Reflection

The manipulation of images is not new and dates back to the beginning of photography.

Photographer Frank Hurley clashed with historian Charles Bean over the authenticity of Hurley’s images. Bean wanted historically authentic images, while Hurley was more concerned with portraying the reality and horrors that soldiers faced in the war.

Hurley engaged in wartime propaganda, while Bean was concerned with the accuracy of the historical record.

Decisions in this area are related to ethics and ‘what ought we do’. The clash between Hurley and Bean raised the question of what the right thing to do was in wartime.

Bean was concerned with authenticity, transparency, accuracy, integrity, and accountability, all of which are central to the current issue of deepfakes.

Deepfakes are illegal in many circumstances, and image manipulation can raise difficult questions about the reputations of institutions and organisations.

The question that must be asked is: ‘What is the right thing to do?’

In wartime, there are no easy answers, as Bean and Hurley found.

References

Bekker, Martin. 2025. How to tell if a photo’s fake? You probably can’t. That’s why new rules are needed. The Conversation, [online] 9 May . doi:https://doi.org/10.64628/aaj.gg5j3npmv. (Viewed 18/1/26)

Bennett, Scott 2023. Is Frank Hurley’s striking photograph genius or trickery? Facebook 27 December. Online https://www.facebook.com/scottbennettwriter/posts/is-frank-hurleys-striking-photograph-genius-or-trickery-the-top-photograph-over-/859655549504329/ (Viewed 19/1/26)

Hutchings, Rod 2026. ‘The story behind this photograph’ Australian Peacekeeper and Peacemaker Veterans’ Association Ltd Facebook. 15 January. Online at https://www.facebook.com/AustralianPeacekeepers/posts/the-story-behind-this-photographin-early-1918-frank-hurley-was-working-in-the-mi/866964315977685/ (Viewed 18/1/26)

Leetaru, Kalev 2019. Why Do We Trust Online Images And Video? Forbes. 28 August. Online https://www.forbes.com/sites/japan/2025/12/10/harnessing-ai-japanese-startups-are-unlocking-enterprise-data/ (Viewed 18/1/26)

Marrone, Stephanie 2020.’ Why You Shouldn’t Believe Everything You See on Social Media’. The Social Media Butterfly. Online https://www.socialmediabutterflyblog.com/2020/10/why-you-shouldnt-believe-everything-you-see-on-social-media/ (Viewed 18/1/26)

Parer, Damien 2026. Frank Hurley: The Man Who Made History, Curators Notes. Australian Screen. Online at https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/frank-hurley/clip2/ (Viewed 18/1/26)

USPA 2025. The Ethics of Photo Manipulation: What Is Acceptable in Modern Press Photography? United States Press Association. 25 July. Online at https://www.unitedstatespressagency.com/news/the-ethics-of-photo-manipulation-what-is-acceptable-in-modern-press-photography/ (Viewed 18/1/26)

Victoria Police 2025, Deepfakes. Victoria Police. 26 June. Online https://www.police.vic.gov.au/deepfakes (Viewed 19/1/26)

Wishart, Alison 2017. ‘Truth and Photography, Frank Hurley’s World War 1 Photography’. State Library of NSW. Online https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/truth-and-photography (Viewed 18/1/26)

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.