Massive fire in Macquarie Street 1882

In 1882, there was a massive fire in Macquarie Street, Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

The beautiful building known as the Garden Palace was totally destroyed by fire together with its valuable contents. The conflagration naturally provided an impressive spectacle and was watched with awe by tens of thousands of people who quickly gathered from all parts of the city. (SMH, 18 April 1931)

The newspaper report stated this apparent

calamity was in reality was a blessing in disguise, for it returned am area of open space to the citizens, of which they should never been deprived, and removed a source of danger that must have grown ever more dangerous with the passage of time. (SMH, 18 April 1931)

The fire, a tragic event that filled the hearts of many with sorrow, resulted in the significant loss of irreplaceable records, artefacts, and other materials. Among the casualties were the records of the 1881 Census, railway surveys, and the Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum, which had been a treasure trove of knowledge since its founding in 1878 by the Australian Museum. This later became the Museum of Applied Arts and Science and the Powerhouse Museum. The fire also claimed the squatting occupation of NSW and around 1000 Aboriginal artefacts, a loss that can never be fully quantified.

The origin of the fire, a puzzle that has intrigued historians and researchers for years, remains shrouded in mystery. Despite its best efforts, the official inquiry could not definitively determine the cause. Speculation, as diverse as the city itself, ranged from the disgruntled wealthy residents of Macquarie Street to the destruction of convict records containing potentially damaging information. (SLNSW)

Sydney International Exhibition 1879-1880

The Garden Palace was originally commissioned in 1878 by the NSW colonial government to house the Sydney International Exhibition. The exhibition’s aim was to contribute to the progress and development of the colony of NSW. The exhibition benefited Sydney, boosted the economy, and improved services in the city. A steam-powered tram was installed in the city to assist movement around the town centre, and after the exhibition, it was expanded and converted to electric traction in 1905.

According to Shirley Fitzgerald in the Dictionary of Sydney

The fashion for holding exhibitions, where countries could show off their industrial and manufacturing might as well as their agricultural riches and artistic skills, began in 1851 with the London Exhibition. It was housed in the purpose-built Crystal Palace. Exhibitions followed in other European cities and in Philadelphia in the United States. Paris was particularly fond of holding them. Then Sydney, a place not noted for its advanced industrial sector, and very far away from other places that were, decided to have a go. (https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/garden_palace)

Royal Agricultural Society

Originally, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW proposed a small international exhibition with a rural theme in 1877 using the society’s exhibition hall in Prince Alfred Park. As the idea gained momentum, the RAS backed out. In 1878, the colonial government set up the Royal Commission for an International Exhibition in Sydney, headed by politician and philanthropist Sir Patrick Jennings.

Like a large cathedral

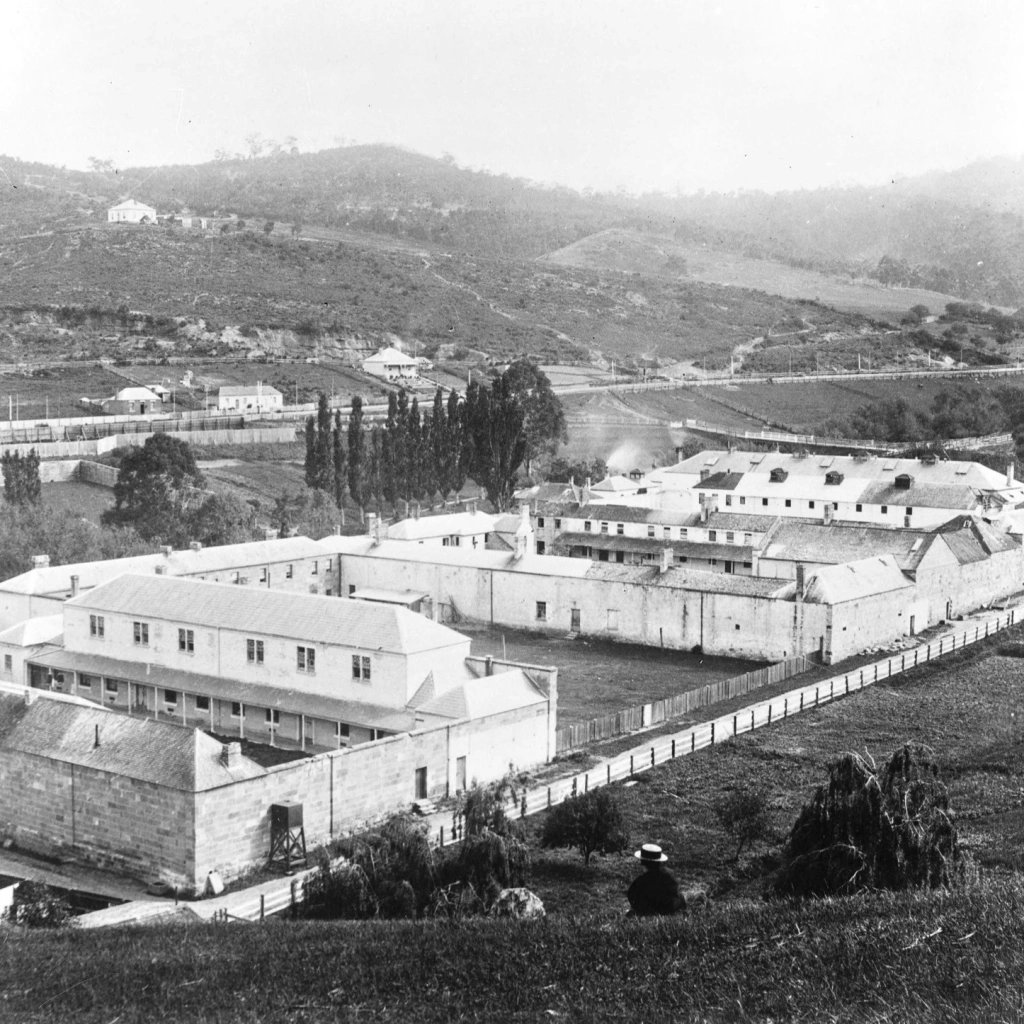

Colonial Architect James Barnet designed the Garden Palace building. It was in a commanding position in the Inner Domain, with a ‘beautiful view of the harbour and its shores’ (ISN, 25 October 1882) at the southwestern end of the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain.

The building was shaped like a crucifix, similar to a large cathedral or London’s Crystal Palace. It was like the later Melbourne Exhibition Centre (b.1879-1880). The Garden Place nave and transept were flanked by expansive aisles, stretched 800 feet from north to south and 500 feet from east to west with towers at each end. The northern tower contained Sydney’s first hydraulic lift.

The nave and transept intersection were crowned by a dome, 100 feet in diameter and 90 feet from the floor, culminating in a lantern that soared 210 feet above the ground. The nave and transept ended in four entrance towers, each standing tall at heights ranging from 120 to 150 feet. The extensive aisles were bathed in natural light from vertical windows, strategically placed to avoid direct sunlight. The basement, too, was illuminated by lofty side windows. The total floor space of this architectural marvel was a staggering 8½ acres. (ISN, 25 October 1882)

Beneath the dome was a fountain with a 25-foot statue of Queen Victoria on top. The dome had a 25-foot diameter skylight dotted with ‘golden stairs’. The galvanised iron roof was coloured light blue. The fronts of the galleries had the names of cities and towns on their panels. (ISN, 25 October 1882)

Construction

Construction took eight months to complete, and was opened on 17 September 1879 at a cost of £192,000 by the Governor of the colony of NSW, Lord Augustus Loftus. Work was carried out around the clock under electric lighting imported from England. Construction was completed by experienced builder John Young, who had worked on the Crystal Palace at The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. The construction job employed around 3000 men and 650 carpenters, using 2.5m bricks, 243 tons of galvanised iron, and 1.4m of timber and glass. (SLNSW)

Official opening

The opening was attended by the governors of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, military and naval officers, foreign dignitaries, and 20,000 members of the general public. (ISN, 25 October 1882)

Commissioner PA Jennings said:

Since the Exhibition of 1851 in London, held under the presidency of the illustrious Prince Contort, whose memory is nowhere more deeply revered than in this colony, universal Expositions, or ‘World’s Fairs have been held in Paris, in Loudon, in Vienna, and in Philadelphia, and the beneficial consequences of those “Festivals of Peace” become more apparent the more their effects are studied. It has remained for this city of Sydney, the metropolis of the parent colony of Australia, to sustain its position by inviting “all the flags of all the world” to range themselves in peaceful concord here to-day. (Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 18 September 1879)

Mr Jennings then invited the governor to open the Sydney International Exhibition 1879.

Governor Loftus said:

In the name of New South Wales, the elder colony of the Australian group, the once despised, and – may I not say – the now honoured, I welcome the representatives of the old heroic nations welcome the representatives of the bright daughter-lands of England- I welcome all of human brotherhood, to our newly raised Temple of Industry and Peace in a new world. (Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 18 September 1879)

The governor then opened the exhibition to the public.

Fine art annexe

The fine art commissioners at the exhibition were not satisfied that the Garden Palace was a suitable space to hang artworks and convinced the exhibition organisers to build a Fine Arts Annexe. Designed by church designer William Wardell and shaped like a crucifix, the annexe opened two months after the exhibition opened. After the exhibition closed, the colonial government gave the building to the NSW Academy of Art in 1880, and the refurbished building was named the National Art Gallery of NSW and retained that title until 1958. (https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/about-us/history/our-gallery-history/history-of-the-building/the-fine-arts-annexe-1880-84/)

The exhibition

The exhibition closed on 20 April 1880 after being open for 185 days and attended by 1,117,536 people, producing a surplus of £41,432. (ISN, 25 October 1882) The remarkable achievement was when the population of NSW was around 650,000.

The cost of admission was 5/-, later dropped to 1/-, and a season pass was £3/3/-. Over 30 countries and colonies, with over 14,000 exhibits, participated in the exhibition. The exhibition provided opportunities for countries to express their national identity and display the latest technology. Exhibits included glass, tapestries, fine porcelain, ethnographic specimens (Aboriginal specimens), and heavy machinery. (SLNSW)

Commemorative sites

Commemorative gates were built on the former site of the Garden Palace in 1889 to commemorate the memory of the Garden Palace.

In 1979, Sir Roden Cutler unveiled a commemorative plaque on the Garden Palace’s central dome site, celebrating the centenary of the first International Exhibition in Sydney in 1879.

The site of the former Garden Palace is now a rose garden within the Royal Botanic Gardens of Sydney.

Legacies

- Powerhouse Museum, formerly the Museum of Applied Arts and Science, formerly Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum (1878)

- Art Gallery of New South Wales, formerly National Art Gallery of NSW (1880)

You must be logged in to post a comment.