Australian Historical Association 2007 Regional Conference

Engaging Histories

University of New England, Armidale

23-26 September 2007

Yearning, Longing and The Remaking of Camden’s Identity: the myths and reality of ‘a country town idyll’

Abstract

This article discusses the concept of a “country town idyll” in Camden, an idealised version of a country town from an imagined past that uses history to construct imagery based on Camden’s heritage buildings and other material fabrics. The paper delves into the origins of the idyll, examines its development, and investigates its validity in its contemporary context. It shows how its supporters have used history as a community asset to remake Camden’s identity and explore how the ‘country town idyll’ has been used variously as a political weapon, a marketing tool, and a tourist promotion.

Key terms: Country town idyll; Heritage buildings; Community asset; Political weapon; Tourist promotion.

Article

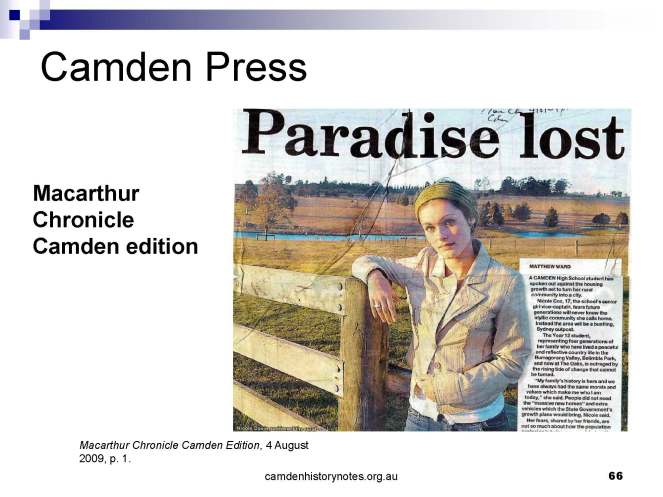

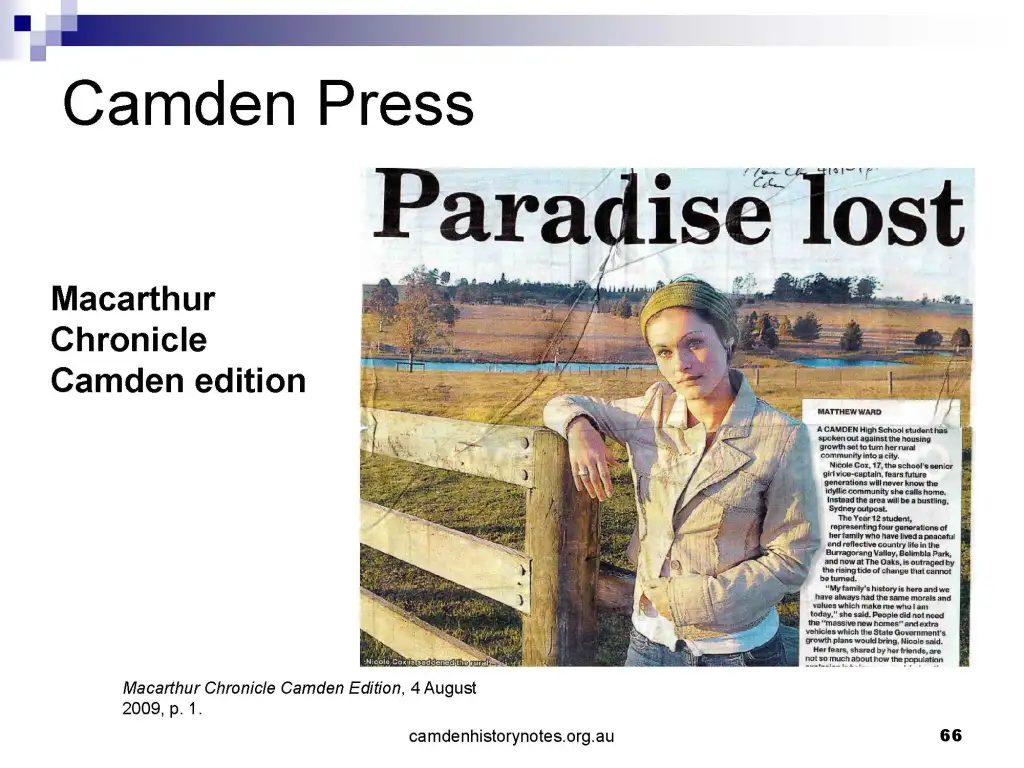

In May this year, the headline on the front page of the Macarthur Chronicle screamed ‘Home Invasion’. The report warned that

The rural landscape surrounding Camden will be engulfed by suburbia when the construction starts on the Oran Park and Turner Rd precincts early next year. More than 30,000 will occupy 11,500 homes in the two precincts, which form part of the South West Growth Centre. By 2030 Camden will be surrounded by new suburbs consisting of up to 181,000 homes as dense as some of Sydney’s most populated areas.[1]

Sydney’s urban expansion into the local area has challenged the community’s identity and threatened to suffocate Camden’s sense of place. In the face of this onslaught, many in Camden yearn for a lost past when Sydney was further away, times were simpler, and life was slower. This nostalgic vision, a type of rural arcadia, which I have called ‘a country town idyll’, holds a significant place in Camden’s history. This paper, unique in its exploration of the ‘country town idyll ‘, aims to delve into this idyll and show how its supporters have used history as a community asset to remake Camden’s identity.

Initially, the paper will define the ‘country town idyll’ and then show that its origins are drawn from the broader traditions within rural studies. The discussion will then examine the idyll’s development and investigate its validity in its contemporary context. This will be done by exploring its values and how it has been adopted by various stakeholders, including local government, businesses, land developers, and community organisations. The paper will also explore how the ‘country town idyll’ has been used variously as a political weapon, a marketing tool, and a tourist promotion. So, what is meant by the term ‘country town idyll’? This question will be answered in the course of our analysis.

What is the country town idyll?

For this paper, the ‘country town idyll’ is an idealised version of a country town from an imagined past that uses history to construct imagery based on Camden’s heritage buildings and other material fabrics. At the heart of the idyll is the view that Camden should retain its iconic imagery of a picturesque country town with the church on the hill, surrounded by a rustic rural landscape made up of the landed estates of the colonial gentry. Its supporters created the idyll to isolate Camden, like an island, in the sea of urbanisation and development that has enveloped the town. The imagery is firmly located in ‘the country’ that Kerrie-Elizabeth Allen maintains, a location of nostalgia where one can experience an idyllic existence. Central to this notion is nostalgia and an escape from the present, where rural life was associated with an uncomplicated, innocent, genuine society in which traditional values persisted and a place where lives were real. Relationships were seen as honest and authentic.[2]

These are the values that the supporters of Camden’s ‘country town idyll’ have encouraged and then expressed in the language they used to describe it. They talk about retaining Camden’s ‘country town atmosphere’, ‘Camden’s country charm’, or ‘country town character’. They describe the town as ‘picturesque’ or having ‘charming cottages’. To them, Camden is ‘ a working country town’ or simply ‘my country town’. These elements evoke an emotional attachment to a place that existed in the past when Camden was a small, quiet country town that relied on farming. So, where did the idyll come from?

The origins of the idyll.

The origins of the ‘country town idyll’ are to be found in the rural ethos that is drawn from within the nineteenth-century rural traditions brought from Great Britain, where there was a romantic view of the country that had an ordered, stable, comfortable, organic small community in harmony with the natural surroundings.[3] This rural culture’s elements have been described as ‘countrymindedness’,[4] ‘rural ideology’[5], ‘rural ethos’,[6] ‘ruralism’[7], and a ‘rural idyll’.[8] They have been a preoccupation of many scholars,[9] including contemporary writers like the Australian poet Les Murray.[10] Within this tradition is an Arcadian notion of a romantic view of rural life, where a distinction is drawn between the metropolis and the village, commonly known as the town/country divide. This was the essence of pre-war Camden, a town of around 2000, where rural culture provided the stability of a closed community which was suspicious of outsiders, especially those from the city, with life ordered by social rank, personal contacts and familial links. It was confined by conservatism, patriarchy and an Anglo-centric view of the world. Camden’s ‘rural culture’ reached a watershed during the 1960s, after which social, economic, and political conditions combined to change Camden’s rurality permanently.

The historical development of the country town idyll and its contemporary use by its supporters

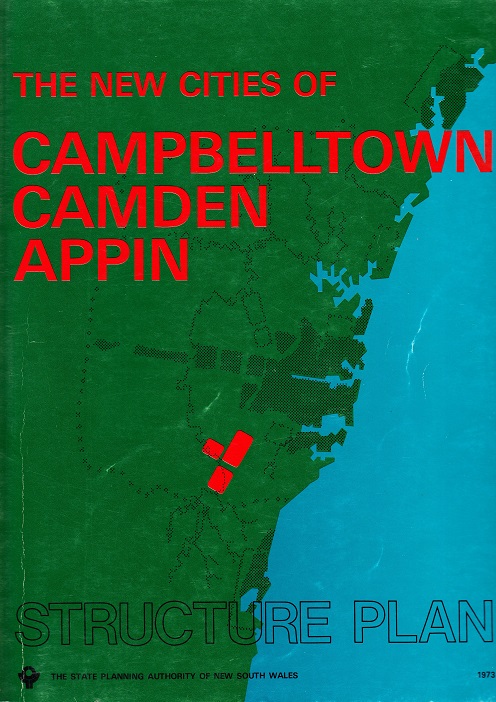

The planned post-war urban growth of Greater Sydney set the conditions for the development of the idyll. Sydney planning authorities had earmarked Camden as part of the Greater Sydney Area and the County of Cumberland Plan as early as 1948. The idea was to form a girdle of countryside around Sydney (a rural-urban fringe) and for Camden to be part of it. In 1968, Camden was included as part of Sydney’s outer rural area in the Sydney Region Outline Plan.[11] While Camden may have been part of each of these plans, they had little direct effect on the township or its rural identity, but this was about to change.

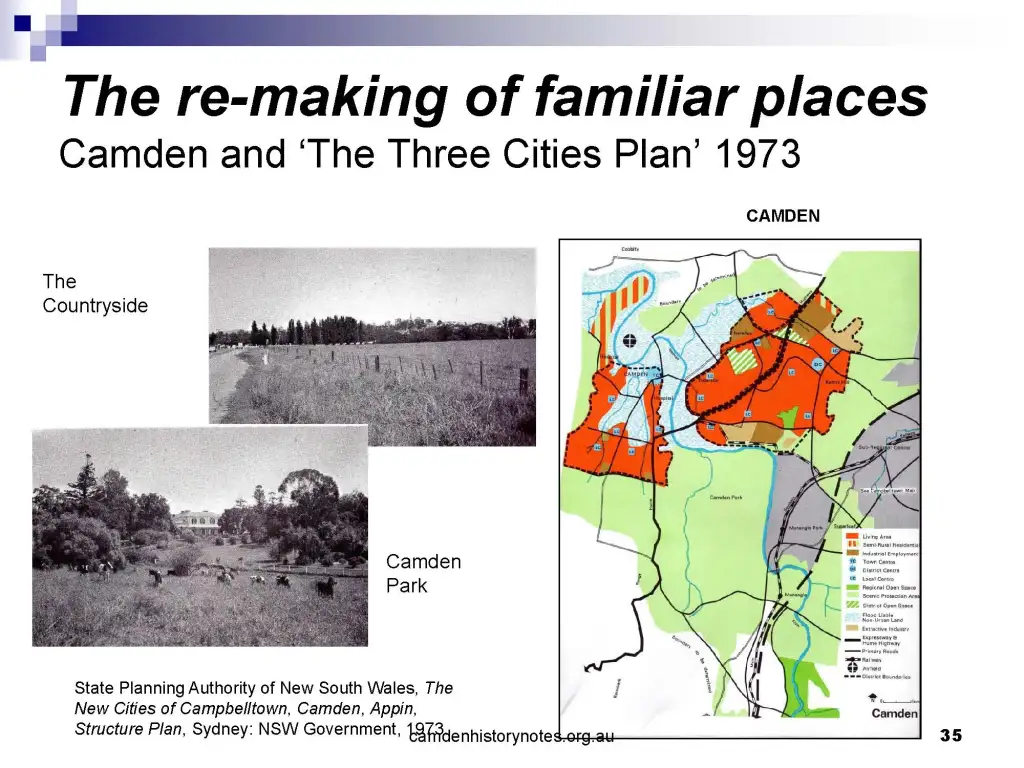

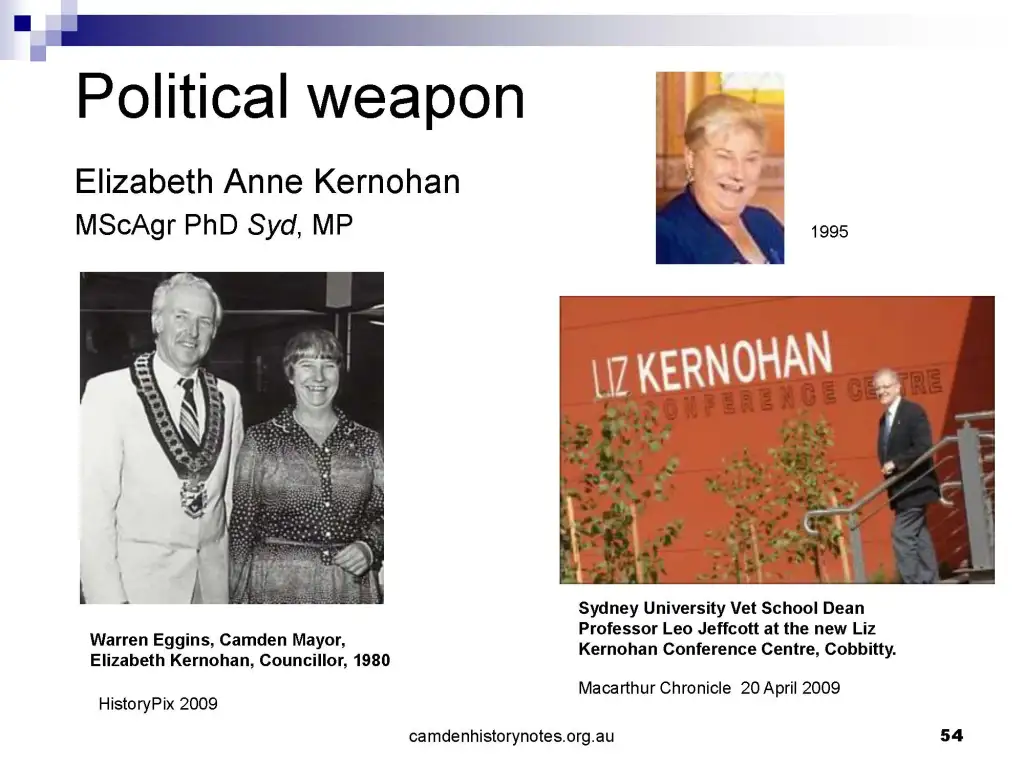

For many, the release of The Three Cities Structure Plan Campbelltown, Camden, Appin in 1973 was a direct assault on Camden’s ‘rural character’. The plan covered Campbelltown, Camden and Wollondilly local government areas, which, according to the plan, were destined to become part of Sydney’s urban sprawl. For one, Liz Kernohan, the structure plan rang alarm bells. She was a scientist who worked at the University of Sydney Farms at Cobbitty, west of Camden.[12] She was a ‘city type’, an outsider, who came to Camden in 1960 and became a strident advocate for retaining Camden’s country town charm, that is, Camden’s country town idyll. The release of the structure plan prompted her to stand for election to Camden Municipal Council. She based her election platform on the retention of Camden’s ‘rural character’, and while she was not the first to take an interest in these values, her election to Camden Council in 1973 helped crystallise the idyll in the minds of many in Camden for the first time.

Kernohan used the values within the idyll as a constant theme throughout her political career, including her election to the New South Wales Parliament in 1991. In her maiden speech to parliament, she stated that her constituents wanted a semi-rural lifestyle and that ‘explosions of suburbia’ did not constitute progress.[13] Kernohan maintained that Camden’s identity and sense of place were built on the town’s historical place and exemplified by Camden Park, the colonial property of John Macarthur and his descendants, and the Camden Museum, managed by the Camden Historical Society. Kernohan used the values within the idyll to create a direct link between Camden’s history and an idealised landscape from the past. She maintained that:

The Camden district [had] the unique history of being the area where the wool and wine industries were developed by the Macarthur family. Camden municipal council [sic] wants to retain the area’s rural heritage and environment and is encouraging developers to enhance the country town image and take cognisance of the history of the area.[14]

Kernohan’s political activity in the early 1970s helped the development of the idyll and contributed to the formation of the Camden Resident Action Group (CRAG). CRAG was one of the first organisations in Camden to advocate the values within the country town idyll publicly, and it received strong support from Kernohan. The members of CRAG felt that Camden’s rural culture was being undermined by urban growth and set out to effectively isolate Camden from Sydney’s urbanisation. The members of CRAG sort historical links through time to strengthen their sense of belonging and participation in space and place. Janice Newton has maintained that these types of progress associations were more nostalgic and defensive and looked to conservation as their ideal, as opposed to progress associations of earlier times that were positive and supported development. [15]

The Camden Historical Society, which fitted the same mould as CRAG, fostered an interest in local history and memorialised Camden’s pioneering past with several civic monuments in the early 1970s.

Newton quotes British research, showing that these ‘peripheral communities have a consciousness and valuing of difference’, an identity of separateness. The identity of difference is one of the central values within the country town idyll. The local community has long held animosity toward Sydney-based decision-makers dating back to the nineteenth century, and this has been expressed as the town/country divide. Kernohan encapsulated these values when she stated that,

Camden will be happy to be known as that large country town on the outskirts of Sydney with its own suburbs; it does not want to become part of suburban Sydney.[16]

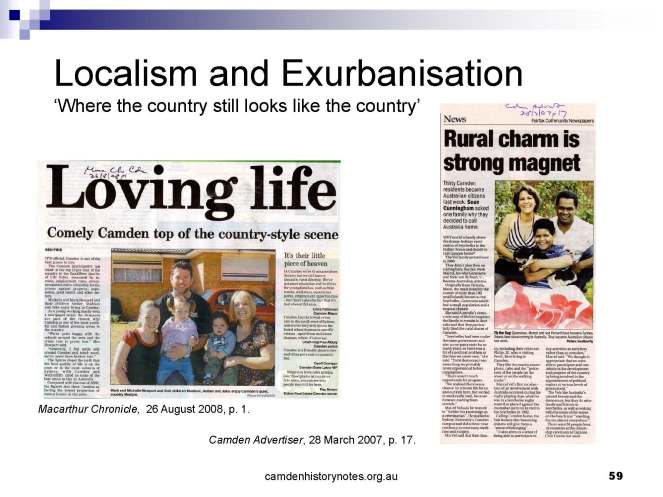

Geographers readily identify this difference as exurbanisation. According to US research, exurbs are ‘places just beyond the suburbs where the country looks like the country’.[17] This is the rural landscape on Sydney’s rural-urban fringe that Camden offers its new arrivals. A rural landscape that promises the new arrivals lots of ‘country town charm’. These city types are looking for greener pastures on the rural-urban fringe where they can escape the city, but interestingly, not the city’s attractions. The values brought to Camden by these new arrivals, including the search for separateness, have altered the community’s subjectivity – the feeling of the community about themselves – and forced a re-evaluation of how the community sees itself, and this is expressed as the country town idyll. Interestingly, the desire by the new arrivals for difference is similar to the values of separateness in gated estates, where residents are trying to isolate themselves from the outside world and the perceived evils of the city.[18] For Camden’s new arrivals, the Camden township is a metaphorical gated estate with the Nepean floodplain as the fence surrounding the estate. They are protected from the evils of the city, such as crime and congestion, by open space in their ‘contemporary country living’—all part of the country town idyll.

Difference and exclusivity within the idyll are supported by Gleeson’s view that areas of new land releases on the fringe of the Sydney Metropolitan Area, like Camden, have become part of an ‘edge city…existing largely in isolation and antipathy to the older cities’. [19] Exclusivity appealed to Camden’s new arrivals who, Kernohan claimed, had come to Camden to ‘escape city conditions’. According to Matt Leighton, the Narellan Chamber of Commerce president, they were ‘refugees’ from the city. [20] Leighton felt they had graduated ‘a step up’ by making their home in Camden. At the same time, others wanted Camden to become the ‘Bowral of Western Sydney’ by ‘attempting to stay out of the fast lane’[21] or maintaining that it should become the ‘Double Bay of the South Western Sector’ of Sydney.[22] Gleeson maintains that the new arrivals were looking to create new ‘urban villages’, which, he claims, is part of a ‘postmodern angst’ where ‘contemporary suburbanisation in Australia is shaped by the mounting anxiety and insecurity among Australia’s urban middle class’. He argues that all this has been fuelled by the ‘neo-liberal restructuring’ of the last 20 years and the ‘new political emphasis on self-provision’. Gleeson claims that this creates ‘aspirational communities’ on the city’s fringe with a high degree of ‘cultural homogeneity’. [23] In other words, Gleeson would maintain that Camden’s new arrivals were looking for a safe and secure environment with predictable lifestyle outcomes in an Anglophile community where their lifetime investment in housing was protected from the city’s threats. This fitted Kernohan’s Camden and the country town idyll she advocated.

Kernohan was a strong supporter of the idyll until she died in 2004, and her success was due, in part at least, to her recognition of the processes associated with the development of the idyll, which has contributed to the changes in Camden’s identity and sense of place. Kernohan encapsulated this process in the language of Camden’s conservative rural tradition and successfully used it in her political platform. She harnessed Camden’s rurality, or what was left of it, and pragmatically voiced the underlying aspirations of Camden’s old and new residents for some sense of stability in the face of constant demographic change in an ideal past. She did this very effectively in 1994 when she opposed a land release by Industrial Equity. Industrial Equity planned a land release at South Camden, at Cawdor, of 4900 lots. There were protests, and a public meeting was held in July, attracting over 300 people.[24] Kernohan campaigned to keep the area ‘pristine’ and had the number of lots reduced to 777, of between 0.4 and 1.0 hectares, and the provision of public housing stopped. The threat from public housing tenants, real or otherwise, would, it was maintained, would undermine the values of privately owned properties on the estate. Industrial Equity’s development was rejected and remains undeveloped. [25] Yet, eight years later, in 2002, Stockland successfully promoted a land release adjacent to this area called Bridgewater. The Bridgewater development is typical of the development found in ‘exurbia’ or Gleeson’s ‘edge city’ that has fostered the country town idyll in Camden.

Over the last five years, the developers of the Bridgewater land release have used the idyll to sell their allotments to locals and city types. It has been advertised as a ‘contemporary rural lifestyle’ and stridently maintained in its press releases that it was not ‘suburbia’. Stockland claimed the estate was within an hour of the city, where ‘second and third homebuyers are looking to upgrade their lifestyle’ and enjoy extensive parklands.[26] Stockland claimed in its 2006 advertising that its development at South Camden was

An idyllic community bordered by undulating countryside, Bridgewater offers the ultimate country lifestyle a mere 50 minutes from the Sydney CBD.[27]

The promotional literature for the Bridgewater land release used images of blond-haired young children frolicking in an idyllic rural vista in the late afternoon light. The images draw heavily on the nostalgia of a carefree childhood in the country, free from the evils of city life. In other promotional literature, Stockland claimed that their estate was

Set in the charming rural enclave of South Camden on Sydney’s metropolitan fringe. Bridgewater offers you the chance to create a new contemporary country lifestyle. Surrounded by the unique heritage and ambience of 19th century farm buildings and homesteads, Bridgewater is the epitome of modern country style, providing innovative, contemporary living in a truly historical Australian setting.[28]

The promotional article is supported by panoramic vistas of Camden’s rural countryside.

Formalisation of the idyll

The first formalisation of the idyll occurred in 1999 with the development of Camden Council’s strategic plan. The strategic plan, which captured community sentiment, was drawn up ‘in consultation with the community’[29] and drew heavily on the values of the idyll. It acknowledged the threat of Sydney’s urban sprawl and the desire for separateness by the community using local history. In the introduction to the plan, it states that

Camden has retained many of the traditional qualities of a rural lifestyle and environment and is characterised by historic towns, country villages and new suburban areas. This has been achieved whilst accommodating the fastest urban growth in the Sydney Region. Importantly, it is not a mere extension of the suburban sprawl by Sydney. [30]

It further maintains that

Camden’s unique rural landscapes and vistas have been retained and improved…[and that]…Camden town has retained its country town atmosphere and culture.[31]

The plan claims that the council recognised the community’s aspirations and the idyll’s role in urban planning within the local government area. It maintains that

The council recognised that economic prosperity and quality of life are linked to its rural identity. The attributes of safety, friendliness and close-knit community associated with rural lifestyle also contribute to the amenity of Camden as a place to live and enjoy.[32]

The council acknowledged that ‘the rural nature of Camden attracts newer residents’ and that ‘the rural landscape is an important factor in the lifestyle of the Camden community’.[33]

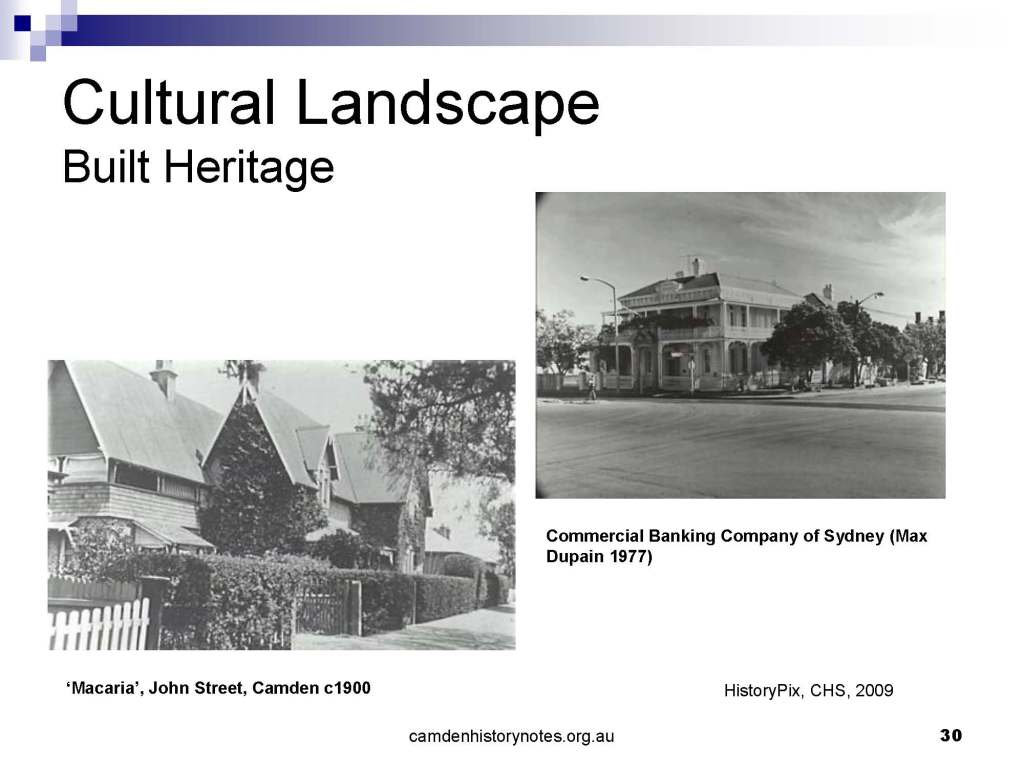

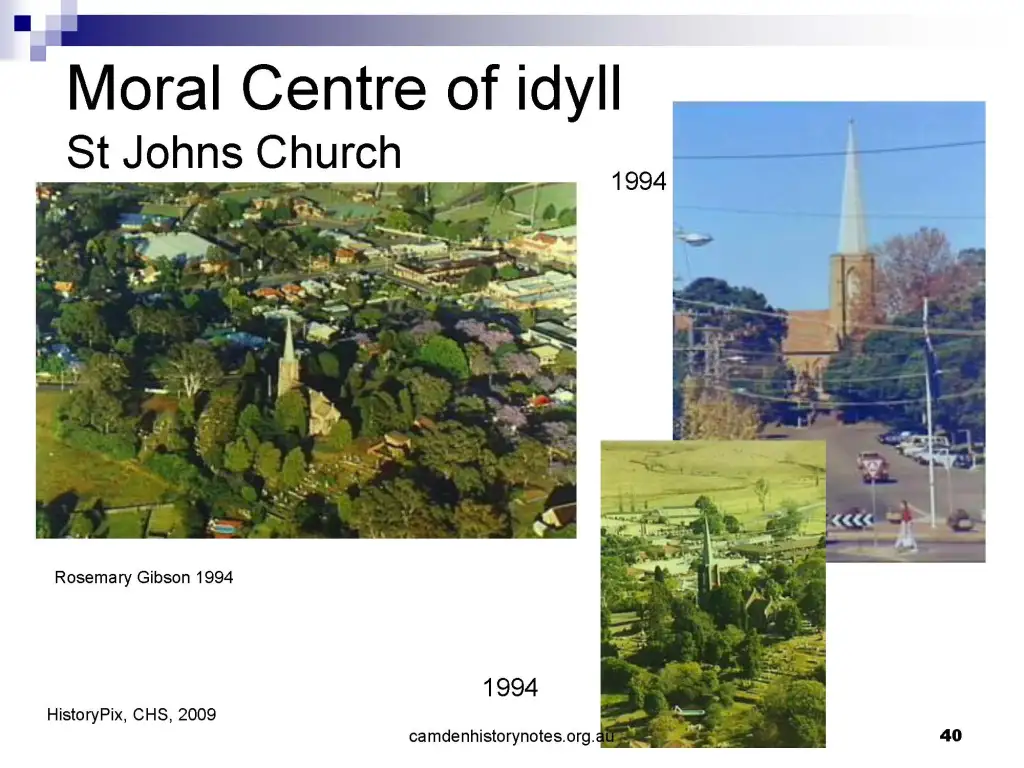

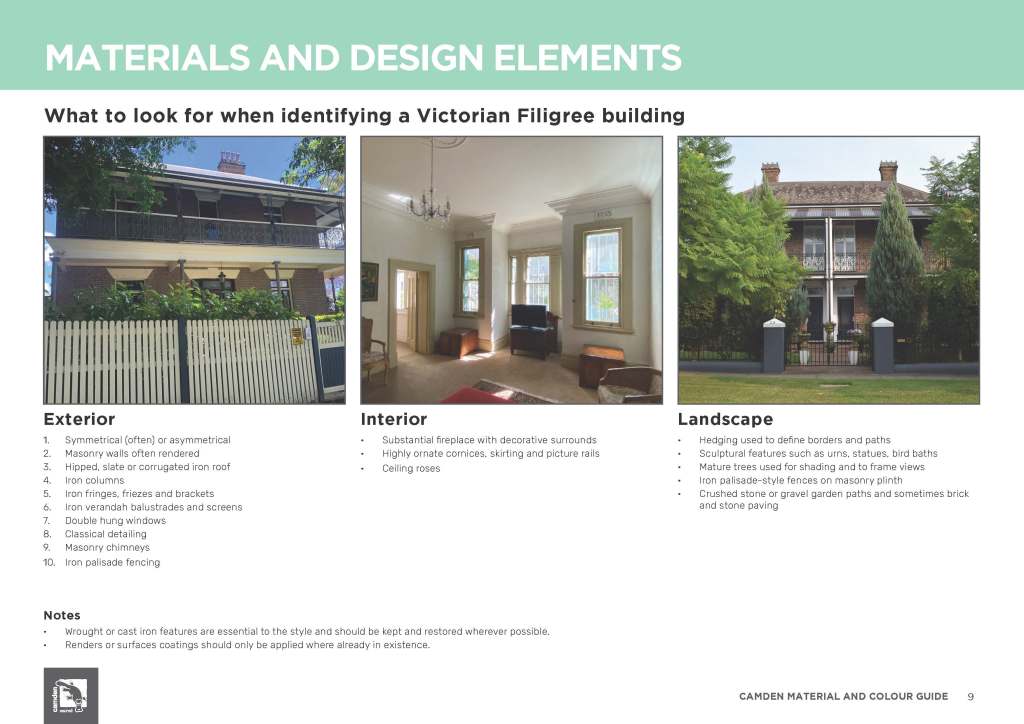

The idyll received a significant boost in 2004 with the completion of the Camden Draft Heritage Plan. While the plan does not formally acknowledge the country town idyll, it uses history to recognise the special status of Camden. The plan identified several unique qualities of the Camden town area, which supported the idyll. They included: the town’s reputation as one of the few original Cumberland Plain country towns still intact; the town’s early farming and settlement history; the area’s sizeable early colonial landed estates; the town’s association with the Macarthur family; the layout of the town that still reflects its original purpose; the arrangement of the town which took advantage of the views and vistas of St Johns Church on the hill. The report recommended: the adoption of the Camden Township Conservation Area based on the original grid plan for the town, which still exists; the mix of colonial buildings in the town area; the mix of residential, commercial, retail and industrial activity in the town area; the rural properties that still exist on the edge of the town centre; the location of the Nepean River floodplain wrapping around three sides of the town; St Johns Church on the hill; and the historical development of the town that is still evident in the properties and usage of the buildings in central Camden.

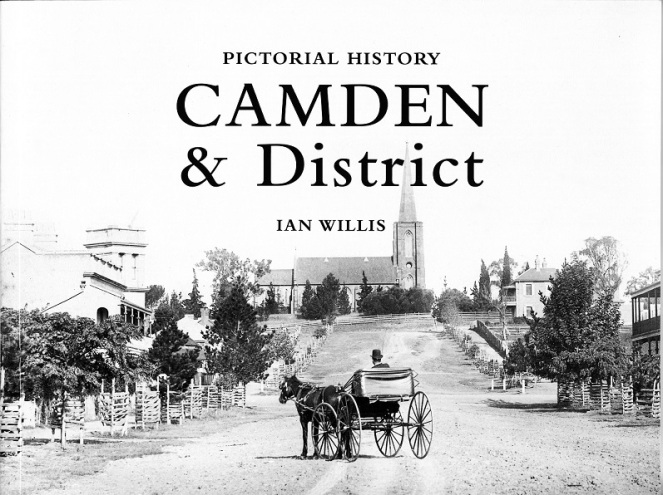

Two aspects of the Draft Heritage Plan[34] warrant special attention as they are critical to understanding the contemporary use of the idyll in Camden, the Nepean River floodplain and the St John’s church. Each has a particular historical, moral, social and psychological significance within the idyll. The supporters of the idyll have used both the Nepean floodplain and St John’s Church and the history associated with them as a political weapon, tourist promotion and part of the construction of heritage iconography. The floodplain is the site of several activities that reinforce Camden’s rural past. They include: the Camden Town Farm, an old dairy farm; Bicentennial Park, an old dairy farm; Camden Showground; the old milk factory of the Macarthurs on the northern approach to the town; and the Camden saleyards, which still operate.

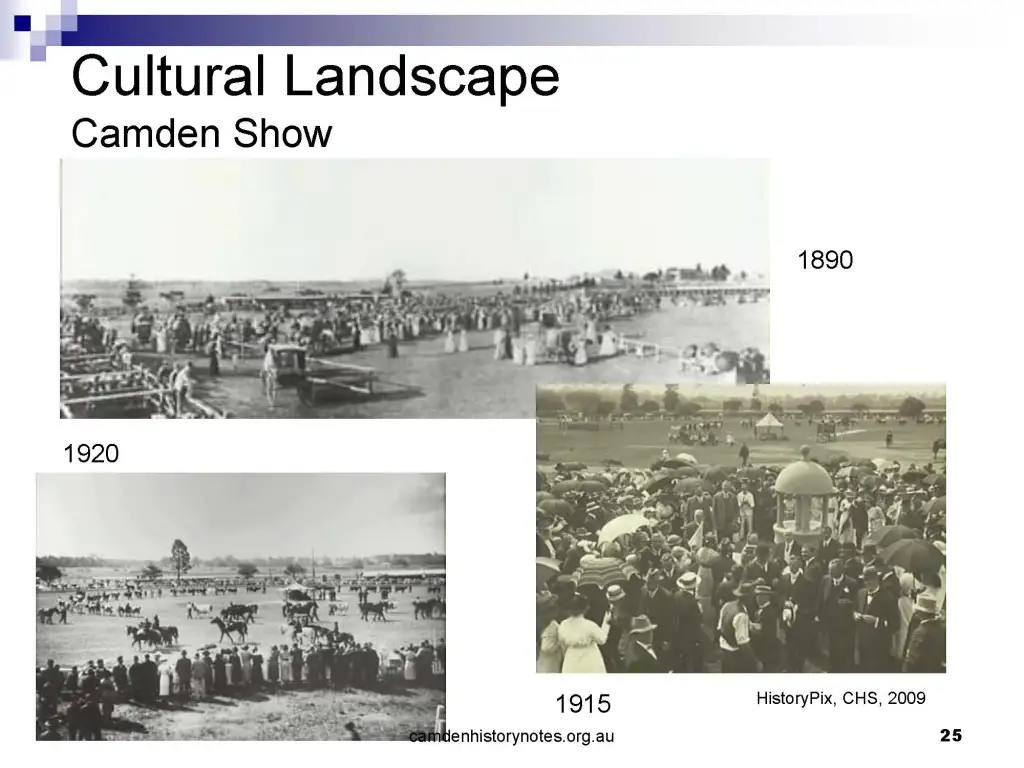

Firstly, the moral imperative of the church on the hill that is St. Johns underpins the values of the idyll and the development of the romantic notions surrounding the town and its past. The church was built on the town’s highest point in 1840 and provides an essential psychological and spiritual focus for the community by dominating the town’s skyline. St Johns is a sacred site associated with the pioneering heritage of the town during the colonial period and the role of the Macarthur family. The Macarthur family ruled over Camden for over 150 years, and the church was central to Macarthur’s moral view of the world and how that should be played out in the town.[35] The town was their metaphysical castle, and they were the squires, especially between 1890 and 1943, when power rested with two Macarthur women, Elizabeth and Sibella Macarthur Onslow. The social authority of these women was absolute. They ensured that the village of Camden reflected their view of the world as much as possible. Nothing escaped their scrutiny or influence, and St Johns was central to their view of the world in Camden. Elizabeth Macarthur Onslow encouraged the maintenance of the proprietaries of life, moral order, and good works, as well as memorialising her family by donating a clock and bells to St John’s Church in 1897.[36] She also memorialised the memory of her late husband by providing a public park named after her husband (Onslow Park), now the Camden Showground. This is one of the sites in Camden that celebrates the idyll each year at the Camden Show. A prominent member of the show committee, Dick Inglis, who was past president,1962-1974, a member of the firm William Inglis and Sons, auctioneers, stock and station and bloodstock agents, and a member of a prominent Camden colonial family, recently claimed that he was proud that the Camden Show was ‘still a country show’ and he hoped that it stayed that way.[37]

Secondly, the geography of the Nepean River floodplain creates a sense of openness around the town or ruralness that engenders a ‘country’ mindset of those who live or would like to live in the local area. The landscape creates a physical and psychological separation from the city. The rural landscape symbolised traditional values embraced by the local community and used in local tourist promotions and by the developers of the new land releases to voice the difference between the local and the metropolitan. This imagery uses nostalgia to connect with Camden’s earlier days when the town was a small rural community and promotes Camden’s ruralness as a positive difference for newcomers to the area. The inundation of the floodplain by the waters of the Nepean River provides a physical and psychological barrier to Sydney’s urbanisation. The floodplain around Camden has been seen as a buffer zone against the onslaught of the city. A moat surrounds the metaphorical castle, that is, the country town. The floodplain provides the moat around the castle.

The Nepean River floodplain and the St John’s Church were invoked within the idyll to defeat a proposal to build a multi-storey carpark in central Camden in 2006. The supporters of the carpark, principally the Camden Chamber of Commerce, wanted additional car parking places in central Camden as early as 1995 because they felt that their financial viability was threatened by competition from Narellan Town Centre, a shopping mall. They thought that a multi-storey carpark would solve their problems. The council considered three possible sites. Two sites were between St John’s church on the hill in central Camden and Camden’s main street (Argyle Street), the third on the floodplain. Camden Council approved a site near St John’s Church in early 2006. The project was eventually defeated because it was felt that any development on the elevated southern sites compromised the vista of St John’s Church from the Nepean River floodplain. The church was located on the hill behind the proposed John Street sites. This vista was part of Camden’s iconic imagery, an important part of the town’s cultural landscape and identity from colonial times.[38] The carpark supporters, the Camden Chamber of Commerce, did not contest this position but felt that the final design of the carpark did not compromise these values; needless to say, Camden Residents Action Group, the historical society and a council-commissioned heritage architect disagreed. The heritage architects felt the proposal compromised the integrity of the ‘most intact country town on the Cumberland Plain’.[39]

Tourist promotions of Camden have drawn on the historic nature of central Camden, including St Johns church, the vistas of the floodplain and the values of the idyll. This has occurred in brochures, promotions, and a recent webpage, which is part of heritage tourism and allows visitors to experience places and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present.[40] The website states that,

Camden’s heritage precinct is dominated by the church on the hill, St John’s Church (1840) and the adjacent rectory (1859). Across the road is Macarthur Park (1905), arguably one of the best Victorian-style urban parks in the country. In the neighbouring streets, there are a number of charming Federation and Californian bungalows.[41]

The webpage continues in a similar vein

The picturesque rural landscapes that surround Camden were once part of the large estates of the landed gentry and their grand houses. A number of these privately owned houses are still dotted throughout the local area. Some examples are Camden Park (1835), Brownlow Hill (1828), Denbigh (1822), Oran Park (c1850), Camelot (1888), Studley Park (c1870s), Wivenhoe (c1837) and Kirkham Stables (1816). The rural vistas are enhanced by the Nepean River floodplain that surrounds the town and provides the visitor with a sense of the town’s farming heritage. [42]

Camden Council, in partnership with Camden Historical Society, produced a brochure for a walking tour of Camden and under the heading ‘Camden Town, A Place in History’ states that,

The historic township of Camden, on the southwestern outskirts of Sydney, is the cultural heart of a region that enjoys a unique place in our nation’s history…This rich rural heritage is evidenced around the town in the presence of livestock sale yards, vineyards, equestrian park and dairy facilities, giving Camden a unique ‘working country town’ atmosphere and flavour.[43]

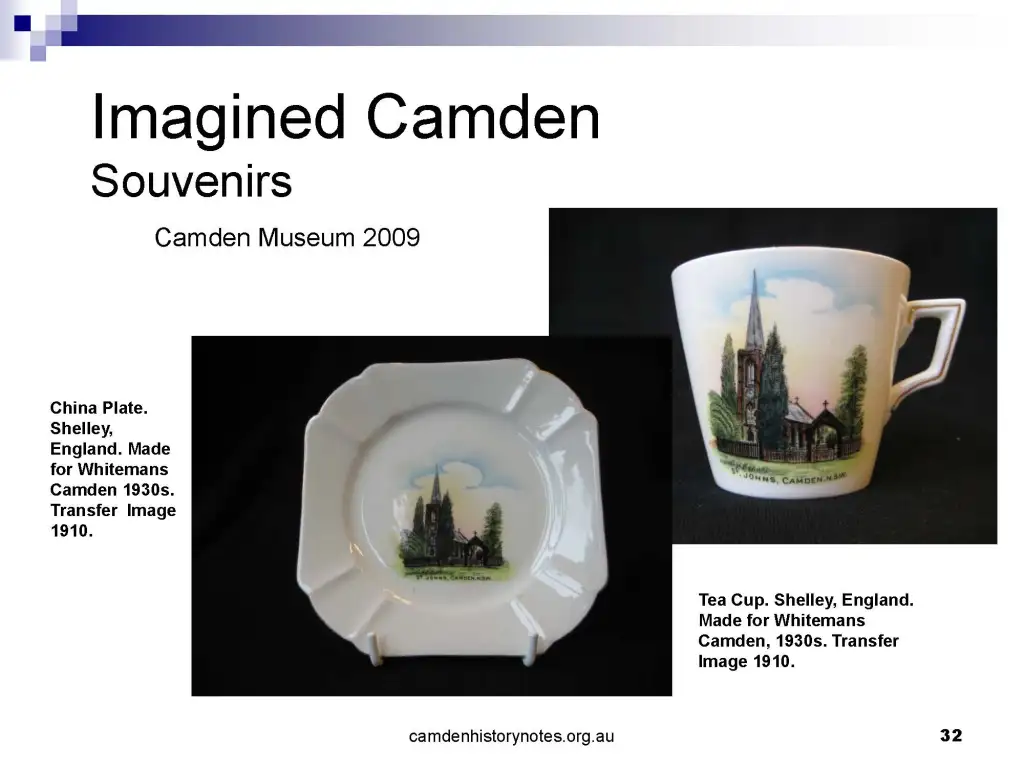

Over the years, St John’s Church has been used on cups, saucers, mugs, and other ephemera.

The same imagery within the idyll is used to promote local businesses. One stockfeed supplier claims to be ‘Keeping Camden Country’.[44] Another business has released a DVD with a slide show and a backing track that uses the values of the idyll in the lyrics of a song written by a local Camden singer/songwriter. The song is called Still My Country Home and is the backing track for a DVD called Camden, Still My Country Home. It has been developed to promote a local business and has all the characteristics of the country town idyll.

Is the idyll still relevant?

Despite the apparent strength of the idyll in Camden, cracks are starting to appear. For example, using the idyll as a political weapon has disappeared, at least in the recent state election in March 2007. Both local candidates from the major political parties, Chris Patterson, Liberal, and Geoff Corrigan, ALP, one the present mayor and one a former mayor of Camden, dropped references to the retention of Camden’s country town atmosphere. Unlike earlier election campaigns involving Liz Kernohan, those values were central to her campaigns for state parliament. This change may be partly reflected by changes to the boundaries of the state seat of Camden and the inclusion of new suburbs in the northern part of the local government area that result from Sydney’s urban growth. In addition, Stockland removed references to ‘contemporary country living’ from promotional literature early in 2007, and the latest land release at East Camden, Elderslie, called Vantage Point, does not mention the idyll.

Yet a recent development application, in May 2007, by McDonalds for a new restaurant in South Camden has seen the idyll used as a potent political weapon yet again and involving the values of the country town. Protesters evoked the values of the idyll against a proposed McDonald’s restaurant in South Camden. The flood of objections from the community centred around concerns that were evocative of the evils of the city coming to invade the country town and revolved around crime, litter, traffic congestion and boorish behaviour. One resident complained that he had witnessed drunkenness, throwing bottles, boorish behaviour and burnouts in the carpark by McDonald’s customers at an outlet in Narellan. He further claimed that all incidents went unchecked by McDonald’s staff, security or police.[45] Helen Stockheim, a resident, claimed that she moved to the area because she liked the ‘country town atmosphere’ and the area was ‘McDonalds free’.[46] The Camden Advertiser ran an editorial titled ‘Let’s treasure our beautiful area’.[47] The giant conglomerate McDonald’s is the ‘outsider’ and brings the evils of the city in the form of globalisation, cultural integration and market domination to Camden. They directly challenge the community’s identity and the values represented by the idyll, such as honesty, simplicity, and authenticity of family-run businesses. The global corporation represents everything that the country town idyll is not.

The future relevance of the idyll to the Camden community is still an open question. The encroachment of Sydney’s urban sprawl is reshaping Camden’s identity in ways which are not yet clearly discernible. Yet many want the rural vistas and the historic buildings that create the separateness of Camden from Sydney’s urbanisation. They are the ones who are trying to hold on to the values of the small town in the form of the country town idyll.

[1] Macarthur Chronicle (Camden Edition) 15 May 2007, p.1.

[2] Kerrie-Elizabeth Allen, ‘The Social Space(s) of Rural Women’, Rural Society, v.12, no.1, 2002, pp31-32.

[3]. Waller, Town, City and Nation, p. 213. This division was based on nostalgia and romance and is still evident in popular contemporary British magazines like Country Origins, This England and The Best of British.

[4].Countrymindedness was ‘Physiocratic, populist and decentralist’. Rural pursuits were seen as ‘virtuous, ennobling and co-operative; they bring out the best in people’, while ‘city life is competitive and nasty, as well as parasitical’. The city was seen as immoral and parasitic, while the country was decent, honest and industrious. Aitkin, ‘Countrymindedness’, pp. 35-36.

[5].Poiner, The Good Old Rule, pp. 30-52; Alston, Women on the Land, pp. 142-147.

[6].Teather, ‘Mandate of the Country Women’s Association’, p. 85.

[7].Neutze, ‘City, Country, Town’, p. 15.

[8].Ward & Smith, The Vanishing Village, p. 7; Davidoff, World’s Between, pp. 46-50; Kerrie-Elizabeth Allen, ‘The Social Space(s) of Rural Women’, Rural Society, v.12, no.1, 2002

[9]. The town/country divide is based on the relationships between people, and Tonnies’s gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft is often considered ‘the classic statement in this tradition ‘Tonnies’s work described gemeinschaft relations as social relations based on ‘blood ties and geographical proximity’, while Gesellschaft relations is a contractual relationship found in the city. Other social philosophers who have seen a rural-urban dichotomy include Weber, Simmel, Durkheim, Marx and Engels, and Park. Ward & Smith, The Vanishing Village, pp. 1-12.

[10] Murray’s Boeotia and Athens (city and the bush).Helen Lambert, ‘A Draft Preamble: Les Murray and the Politics of Poetry’. APINetwork.Online. < http://www.api-network.com/main/index.php?apply=scholars&webpage=default&flexedit=&flex_password=&menu_label=&menuID=homely&menubox=&scholar=58> Accessed 14 May 2007.

[11] Bunker Raymond and Darren Holloway, ‘More than fringe benefits: the values, policies, issues and expectations embedded in Sydney’s rural-urban fringe’, Australian Planner, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2002, p. 68

[12] In 1936, The University of Sydney purchased a dairy farm at Badgery’s Creek and, in 1954, Corstorphine and May Farms at Cobbitty. In 1962, more farms were donated at Bringelly L Copeland (ed), 1910-1985 Celebrating 75 Years of Agriculture at the University of Sydney, Sydney: University of Sydney, 1985, p.46.

[13] NSWLAPD, 16 October 1991, pp.2293

[14] NSWLAPD, 16 October 1991, pp.2293-2294

[15] Janice Newton, ’Rejecting Suburban Identity on the Fringes of Melbourne’, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 1999, 10:3, pp. 322-329

[16] NSWLAPD, 16 October 1991, pp.2293-2294

[17] Tom Foreman, ‘Exurb growth challenges US cities’, CNN.com http://www.cnn.com/2005/us/03/27/urban.sprawl/ . Online. [Accessed 25 May 2007]

[18] Jane Cadzow, ‘Do Fence Me In’, Good Weekend, 5 May 2007, pp33-38.

[19] Brendan Gleeson, ‘What’s Driving Suburban Australia?’, in Griffith Review, special edition ‘Dreams of Land’, Summer 2003-2004.pp. 57-65.

[20] Macarthur Advertiser 16 August 1995; Camden News 22 August 1973.

[21] Macarthur Advertiser 16 August 1995.

[22] The Crier 18 March 1981.

[23] Brendan Gleeson, ‘What’s Driving Suburban Australia?’, in Griffith Review, special edition ‘Dreams of Land’, Summer 2003-2004.pp. 57-65.

[24].The meeting took place at the Camden Valley Inn on 16 July 1994. Camden Crier 17 August 1994.

[25] Camden and Wollondilly Times 14 September 1994; ‘Mini City Proposal Stopped’, Pamphlet, August 1994, Kernohan File, Camden Historical Society Archives.

[26] Macarthur Advertiser 11 September 2002.

[27] Stockland, Upgrade Your Lifestyle, (Stockland Sales and Information Centre, 2006, Advertising Brochure)

[28] Stockland, ‘Bridgewater, Contemporary Country Living’, Aspect NSW, Spring/Summer 2005, pp. 36-37. (Advertising Literature).

[29] Camden Council, Statement of Affairs, Camden: The Council of Camden, 2007, p.3.

[30] Camden Council, Camden 2025, A Strategic Plan For Camden, (Camden: Camden Council 1999).p. 2. Online. http://www.camden.nsw.gov.au (Accessed 14 December 2006)

[31] Camden Council, Camden 2025, A Strategic Plan For Camden, (Camden: Camden Council 1999).p. 2. Online. http://www.camden.nsw.gov.au (Accessed 14 December 2006)

[32] Camden Council, Camden 2025, A Strategic Plan For Camden, (Camden: Camden Council 1999).p. 18. Online. http://www.camden.nsw.gov.au (Accessed 14 December 2006)

[33] Camden Council, Camden 2025, A Strategic Plan For Camden, (Camden: Camden Council 1999).p. 18. Online. http://www.camden.nsw.gov.au (Accessed 14 December 2006)

[34] Camden Council adopted the Camden Draft Heritage Report in December 2006.

[35] Atkinson, Camden; Willis, ‘The Gentry and the Village’;

[36] RE Nixon & PC Hayward (eds), The Anglican Church of St John the Evangelist Camden, New South Wales, Camden: Anglican Parish of Camden, 1999, pp. 8-21.

[37] District Reporter, 24 August 2007, p. 4.

[38] For example, this vista is on the front cover of Paul Power’s A Century of Change, One Hundred Years of Local Government in Camden (Camden: Macarthur Independent Promotions, 1989).

[39] Camden Advertiser 28 June 2006, p. 1.

[40] National Trust for Historic Preservation, ‘Heritage Tourism’. http://www.nationaltrust.org/heritage_tourism/index.html Online. [Accessed 4 April 2007]

[41]Ian Willis, ‘Camden, the best-preserved country town on the Cumberland Plain’, Heritage Tourism <http://www.heritagetourism.com.au/discover/camden.html> Online. Accessed 23 May 2007.

[42]Ian Willis, ‘Camden, the best-preserved country town on the Cumberland Plain’, Heritage Tourism <http://www.heritagetourism.com.au/discover/camden.html> Online. Accessed 23 May 2007.

[43] Camden Council, Heritage Walking Tour of Camden Town, (Camden: Camden Council, 2001)

[44] Advertisement: ‘Regal Stockfeeds’, District Reporter 24 August 2007, p. 6.

[45] ‘Traffic with that ?’, Camden Advertiser, 27 June 2007, Online. http://www.camdenadvertiser.com.au/2007/06/traffic_with_that.php [Accessed 27 June 2007]

[46] ‘Ready for a bun fight’, District Reporter 1 June 2007, p. 3.

[47] Camden Advertiser 27 June 2007, p. 4.

You must be logged in to post a comment.