Murals brighten up dull spaces around town

Keep your eyes open in central Campbelltown for inspiring public art installations that brighten up dull spaces around the town.

The Campbelltown Arts Centre, in conjunction with Campbelltown City Council and the NSW Government, have a program to re-invigorate the city centre using public art.

Public art positively affects the community and people’s self-esteem, self-confidence and well-being. Campbelltown Arts Centre has created a public art website to assist people in this process and shows several murals around the Queens Street precinct.

This blog has promoted the benefits of public art in and around the Macarthur region for some time now. There are lots of interesting public artworks around the area that are hidden in plain sight. This blog has highlighted the artworks and other artefacts, memorials and monuments that promote the Cowpastures region.

An exciting local example is the Campbelltown Campus of Western Sydney University is a vibrant sculpture space.

The public art program of the Campbelltown Arts Centre and Campbelltown City Council is creative, innovative and inspirational. It is playful yet takes a serious approach to a contemporary problem, urban blight.

Urban blight hits a once-vibrant retail precinct

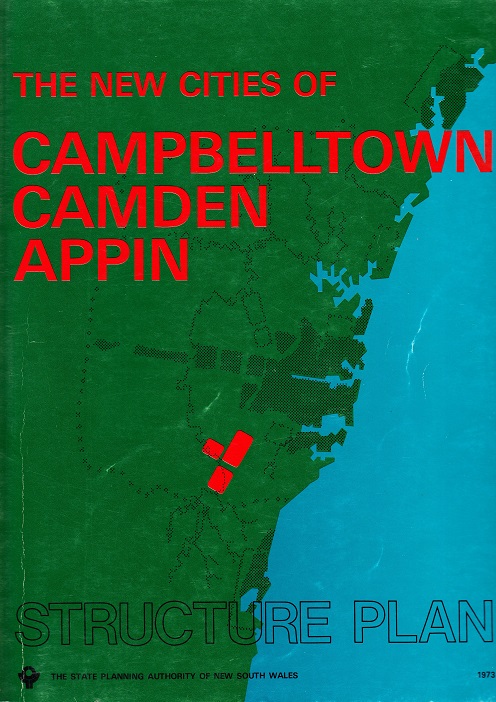

Campbelltown’s urban blight originates in the 1973 New Cities of Campbelltown Camden Appin Structure Plan and the creation of the Macarthur Growth Centre.

These urban planning decisions came from the 1968 Sydney Regional Outline Plan of the NSW Askin Coalition Government.

Sydney-based planning decision created tensions between Campbelltown City Council and the Macarthur Development Board around what constituted the city centre. The Queen Street precinct, supported by the council, gradually declined in importance as a retail area as newer facilities opened up.

Queen Street could not compete with the new shopping mall Macarthur Square opened in 1979 by the Hon. Paul Landa, Minister for Planning and Environment in the Wran Labor Government.

High-value-added retailing deserted the Queen Street precinct and became populated by $2-shops and op-shops.

Campbelltown’s sense of place and community identity has taken a battering in the following decades.

Reinvigoration of the Queen Street precinct

The public art program at the Campbelltown Arts Centre is trying to ameliorate the problems of the past through community engagement in art installations.

In 2022 Mayor George Griess said

The murals would enhance the local streetscape and make the area more welcoming to residents and visitors.

“The first mural is located at one of the entrances to the CBD and will add a new element to our public domain,” Cr Greiss said.

“It’s important that works to the Queen Street precinct enhance the current amenity to build pride among residents and make the area more attractive to people visiting our city,” he said.

https://www.campbelltown.nsw.gov.au/News/CBDmurals

The mayor referred to an art installation created by Campbelltown street artist Danielle Mate ‘Raw Doings’ in Carberry Lane. The Arts Centre website states:

This vibrant and bold artwork comprises many shades of blue and purple, and is inspired by aerial views of Country and the Australian landscape.

https://c-a-c.com.au/raw-undoings/

In 2022 the Campbeltown City Council commissioned ‘Breathing Life / Bula ni Cegu / Paghinga ng Buhay’ by artists and designers Victoria Garcia and Bayvick Lawrance.

The Arts Centre website states:

‘Breathing Life’ is a celebration of Campbelltown’s thriving Pacific community, and the extensive connections between people, plants, animals and all living things.

https://c-a-c.com.au/breathing-life/

In 2012 Campbelltown City Council commissioned a mural board across the bus shelters at Campbelltown Railway Station supervised by Blak Douglas in Lithgow Street called ‘The Standout’. The art installation is the work of 28 artists across 70 panels with a full length of 175 metres.

The Arts Centre website states:

The Standout pays homage to the Dharawal Dreamtime Story of the ‘Seven Eucalypts’, and Douglas’ previous photographic series of deceased gums standing alone within landscapes and casting shadows within urban facades.

https://c-a-c.com.au/the-standout-by-blak-douglas/

The public art installation ‘Three Mobs’ by Chinese-Aboriginal artist Jason Wing was commissioned by Campbelltown City Council in 2022. The mural is located on Dumersq Street and Queen Street, the south side of the 7Eleven wall, and features a rainbow serpent as an intersection of cultures.

The Arts Centre public art website states:

Aboriginal culture reveres the rainbow serpent as the creator of all things on Earth. Chinese culture understands serpents to be a symbol for luck and abundance, and a highly desired zodiac sign.

https://c-a-c.com.au/three-mobs/

So what is public art?

Camden Council defines public art as:

Defined as any artistic work or activity designed and created by professional arts practitioners for the public domain, Public Art may be of a temporary or permanent nature and located in or part of a public open space, building or facility, including façade elements provided by either the public or private sector (not including memorials or plaques).

Public art can….

https://yourvoice.camden.nsw.gov.au/public-art-strategy

- make art an everyday experience for residents and visitors

- take many forms in many different materials and styles, such as lighting, sculpture, performance and artwork

- be free-standing work or integrated into the fabric of buildings, streetscapes and outdoor spaces

- draw its meaning from or add to the meaning of a particular site or place.

Why does public art matter?

On the website Americans for the Arts (2021) it states:

Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas.

https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/PublicArtNetwork_GreenPaper.pdf

The paper maintains that public art has the potential to reinvigorate public spaces and add to their vibrancy. It states:

Throughout history, public art can be an essential element when a municipality wishes to progress economically and to be viable to its current and prospective citizens. Data strongly indicates that cities with an active and dynamic cultural scene are more attractive to individuals and business.

https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/PublicArtNetwork_GreenPaper.pdf

What is the purpose of public art?

The Association for Public Art (2023) website says:

Public art can express community values, enhance our environment, transform a landscape, heighten our awareness, or question our assumptions. Placed in public sites, this art is there for everyone, a form of collective community expression. Public art is a reflection of how we see the world – the artist’s response to our time and place combined with our own sense of who we are.

associationforpublicart.org/what-is-public-art/

Updated 17 May 2023. Originally posted on 16 May 2023 as ‘Public art at Campbellton brightens up a dull space’.

![Camden Whitemans General Store 86-100 Argyle St. 1900s. CIPP[1]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/camden-whitemans-general-store-86-100-argyle-st-1900s-cipp1.jpg)

![Camden Whitemans Store 1978[1] CIPP](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/camden-whitemans-store-19781-cipp.jpg)

![Campbelltown WSU Sculptures 2018[7]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/campbelltown-wsu-sculptures-20187.jpg)

![Campbelltown WSU Sculptures 2018[4]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/campbelltown-wsu-sculptures-20184.jpg)

![Campbelltown WSU Sculptures 2018[3]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/campbelltown-wsu-sculptures-20183.jpg)

![Campbelltown WSU Sculptures 2018[2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/campbelltown-wsu-sculptures-20182.jpg)

![Campbelltown WSU Sculptures & Grounds 2018[2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/campbelltown-wsu-sculptures-grounds-20182.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.