Something to Say art installations

Young people are often described as having nothing to say. Well, at Oran Park, outside the Camden Council administration building, there is a series of artworks that have Something to Say. The artworks are part of the Camden Council’s Camden Council’s Youth Participation Public Art Program, which began in 2016.

These works are described as temporary art installations. They were created by young women artists between the ages of 12 and 24. The artists were encouraged to tell their own stories within their own communities and enhance their skills as artists.

The aim of the public art program is as

a place making initiative that encourages local youth and artist collaboration to create vibrant spaces that foster a sense of belonging and identity.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Artworks often tell stories through a series of images or by selecting a moment in time. These are narrative works that illustrate aspects of an artist’s life or some historical event, cultural festival, religious theme, or perhaps a legendary figure or mythic character.

The J Paul Getty Museum states that teaching young people stories in art involves lessons that

will build students’ awareness of how stories can be told visually and how artists use color, line, gesture, composition, and symbolism to tell a story. Students will interpret and create narratives based upon a work of art and apply what they have learned to create works of art that tell a story.

https://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/classroom_resources/curricula/stories/

The young women who participated in the Something to Say program worked with local Menangle artist Michele Arentz.

On the Camden Council website, each of the artists in the program has issued a statement of intent or a statement that outlines the story that each of the artists tell in their works.

These young women are from different cultural backgrounds and have used their agency to tell intensely personal stories. The stories reflect a diversity of life experiences and provide an insight into the minds of Gen Z.

The artworks reflect different storytelling techniques across a range of art mediums and styles.

Women artists and their statements of intent

Team leader

Michele Arentz @marentzy

In my artwork, I have tried to create a symbolic representation of the elements that the young people in the Something to Say program have chosen to identify as having a positive influence in their lives to date or into their futures.

For example, the elements I have tried to convey in my artwork are featured around family support, promoting togetherness and strength of character, links to community via faith and sport, creativity, expression through artmaking, and achieving academically and spiritually.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Young women artists

Ayesha Khan @ajk_afflatus

My artwork depicts women of all different ages and ethnicities in a public bathroom looking at a mirror. It is a reflection of all the different walks of life that people come from, as well as women’s empowerment. These women all have different careers or roles they play in life, from mother to fast food worker, doctor to student.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Channie Chu

I decided to create this artwork as it incorporates some of my favourite things in life that I love, including art, the city and flowers. These express who I am and what I love. This artwork is made with acrylic paint and posca paint markers.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Eashtha Inavolu

My artwork is based upon a picture of me that was taken during a family trip. The painting reflects my love for nature and plants. The colourful flowers on the heart represent all the people who bring joy to my life. I chose to paint this because it embraces who I am in an indirect way.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Evie Hay

My Something to Say project is about the struggles and challenges in life that relates to all audiences. It’s about the importance of having positivity, community and creativity to push you towards your goals.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Jade Stein

With this painting, I wanted to visualise the warmth and community that can be found in churches all across the Camden LGA. To do this, I gave my impression of a familiar building, St John’s Anglican Church, surrounded by a diversity of people spending time with each other in the afternoon light. Although the historical structure is almost 200 years old, it is still a place of fellowship for the community. I also wanted to emphasise the role that any place of meeting or worship can have in bringing people together and developing a sense of belonging and connection.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Jessica Beck

In my artwork, I have painted a Barbie doll with the words “Life Is Short Make Every Hair Flip Count” to represent the role of a female. This is not just because Barbie has become a huge influence for children, in particular girls, but because as we grow, we long for the days when we knew who we were and weren’t aware of our passion being destroyed by the real world. This painting represents that we can still regain the confidence and innocence that we once had by simple things like flipping your hair.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Karrin Smith-Down

My artwork is called ‘The Fridge’. Members of the local community may have personal issues and concerns, but not many know how to reach out for help. For this artwork, I convey services and ways to reach out through post-it notes on a fridge, which is where people put most of their important things.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Lana Johnstone

In loving memory of Olive McAleer.

This artwork is inspired by my late great-grandmother Olive McAleer’s artworks. Family and heritage are an important part of my life. I wanted to display this through a clear connection between my artwork and my grandmother’s artworks, from the brushwork to the colours to the type of flower – white camellias. I wanted to add my own unique features to the artwork, with the Australian flowers seen. I am passionate about caring for and protecting Australian nature and wanted to include that to merge aspects of my life into my grandmother’s artwork.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Srihitha Nagella

I painted this on my board because it holds some of my favourite moments. The pink moon represents the blood moon that I have always wanted to see. So, the night of the eclipse I waited all night and then fell asleep when it rose. The African violets represent the ones on my windowsill.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

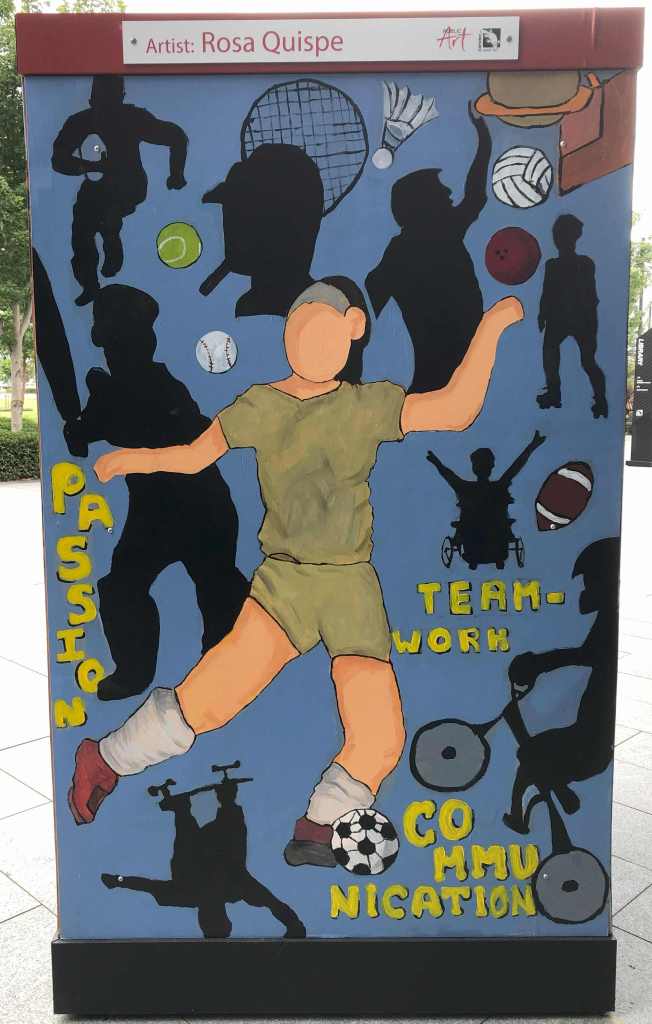

Rosa Quispe

My artwork is based on how sport brings everyone together. I show a little of each sport, whether it is a ball or a player. As a personal touch, I decided to highlight football, since football has helped me to understand Australia’s culture and blend with the people in the community. I added keywords, such as ‘communication’, which means that through sport we can know other people better. ‘Passion’ that motivates people to commit in sports and be able to achieve their goals. Lastly, ‘teamwork’ is in every sport, whether it is played 1vs1 or in groups. It always involves supporting and helping each other. My main message to get across is that sports leads to people being united and being a big family, without exception.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/community/support/cultural-development-and-arts/camden-council-public-arts/something-to-say-eoi/

Concluding Remarks

These art installations demonstrate how art can contribute to community-building through the construction of placemaking.

Public art encourages cultural tourism by promoting community identity and a sense of place. These factors contribute to job creation and the enhancement of local business opportunities.

All photographs are by Ian Willis unless otherwise indicated.

Updated on 29 March 2024. Originally posted on 22 March 2024 as ‘Public art by young women artists on display at Oran Park’.

You must be logged in to post a comment.