Independent Scholars Association of Australia 2015 Conference

Celebrating Independent Thought: ISAA Twenty Years On

National Library of Australia, Canberra ACT

1.30pm, Friday, 2 October 2015

Abstract

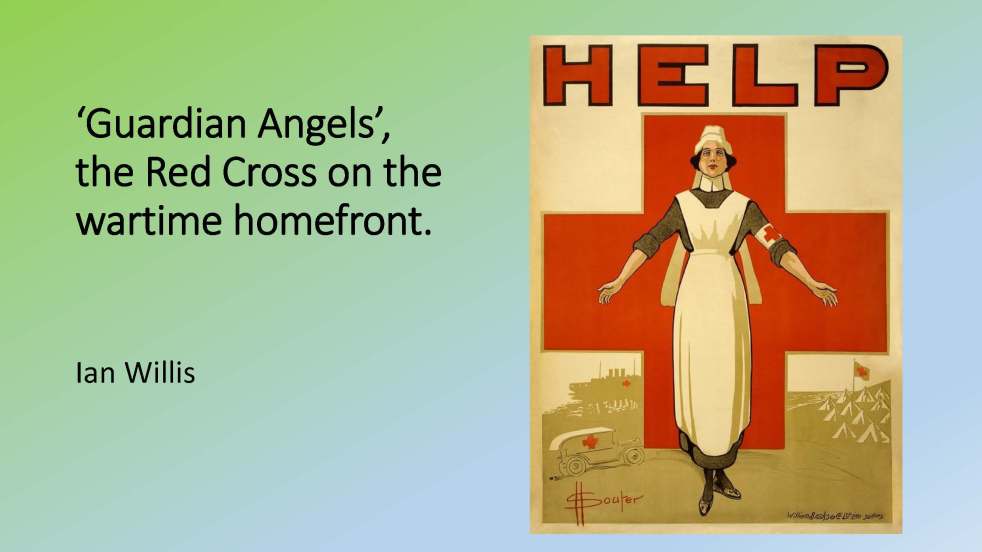

Thousands of women rallied to the call of the wife of the Governor-General and formed Red Cross branches across Australia at the outbreak of the First World War. Women sewed, knitted and cooked for God, the King and Country and were encouraged to see themselves as ‘guardian angels’ serving ‘their boys’ and the imperial cause. Local Red Cross branches harnessed and thrived using parochialism and localism for national patriotic purposes and received considerable community support. The broader Red Cross organisation supported an iconography of motherhood, which gave Red Cross volunteers considerable kudos and agency. By the war’s end, they effectively owned the homefront war effort.

Presentation Slides

Paper

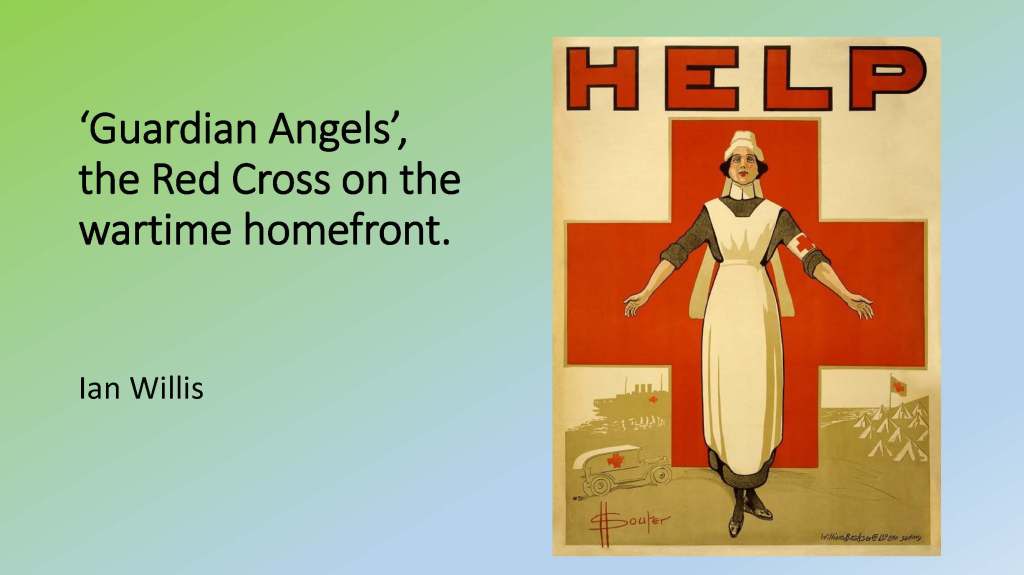

At the beginning of the First World War in August 1914, women across Australia independently exercised their agency and joined the newly formed Red Cross. Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, the Edwardian wife of the Australian Governor-General who had extensive experience in the Scottish Red Cross, appealed to Australian women to form local branches. At a time when patriarchy was the norm, thousands of women joined up and, through their efforts, created one of Australia’s most influential community organisations.

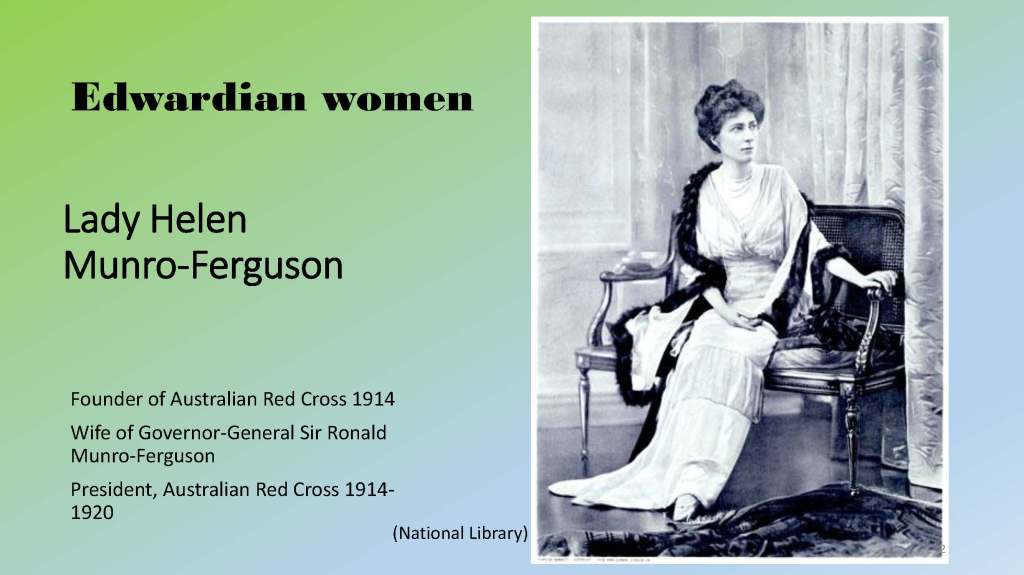

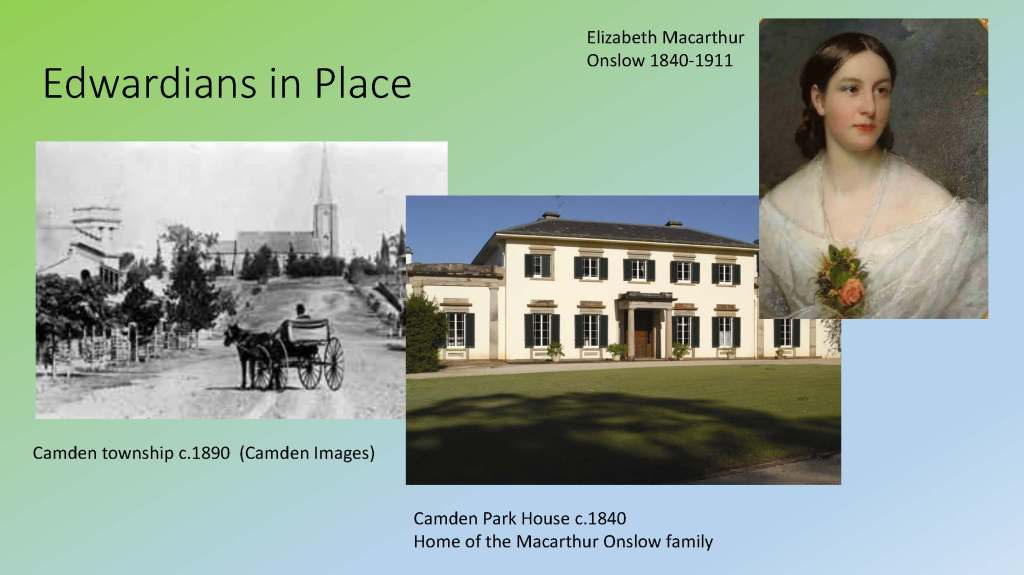

In the small New South Wales dairying town of Camden, some of the fifty women who founded the local Red Cross branch in August 1914 had done all this before. During the Boer War, Camden’s Edwardian female elite encouraged local women to send off soldier comforts to the local unit of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles. They compiled a list of useful items, including stationery, tobacco, pipes, pencils, hand-made socks, shirts, mufflers, belts and caps. Led by the Macarthur Onslow women of Camden Park, these women undertook patriotic fundraising, as their forefathers had done in the Crimean War, and established a local branch of the New South Wales Patriotic Fund (1899). Their wartime spiritual needs were met by joining the newly formed branch of the Mothers’ Union, a prayer group which also made comforts and undertook hospital visits.

The Boer War experiences of Miss EJ ‘Nellie’ Gould encouraged her to try and establish a Red Cross branch within the Women’s Liberal League in 1911, similar to the Red Cross League formed by the Duchess of Montrose and Princess Christian in Scotland.[1] Miss Gould was the Lady Superintendent of the New South Wales Army Nursing Service, which served in South Africa in 1900. The Women’s Liberal League, which had 11,000 members by 1907, was one of the earliest women’s organisations in New South Wales with an extensive branch structure,[2] which was later critical to the success of the Red Cross across the country. Miss Gould felt that as women had acquired the vote, they should also make an equal contribution to the country’s defence by being trained to look after wounded soldiers, and proposed that Red Cross depots be established in preparation for war.[3] In the end, her proposals went nowhere. Miss Gould was later given charge of the Central Depot of the Red Cross in Sydney in 1914, and she served on the divisional executive committee for many years.

In mid-1913, there was a meeting in the library of the British Medical Association in Sydney to set up a branch of the British Red Cross, but nothing eventuated.[4] The following year, there was more success at the home of a Woollahra resident when Dr Roth, an early promoter of the Red Cross, lectured on first aid and stretcher work for the wounded. This was followed up in July by a talk given by Lady Helen Munro Ferguson on the work of the Voluntary Aid Detachments, and in August, she sent out her national appeal to form local branches. There was a strong response of support, and the New South Wales headquarters opened for business in Sydney city, and local committees appeared, starting with the Women’s Liberal League (11 August), the Sydney Lyceum Club (12 August) in the city, followed by suburban branches at Westmead (12 August) and a meeting at North Sydney Town Hall aimed to set up Red Cross activities between Manly and Hornsby (12 August).[5]

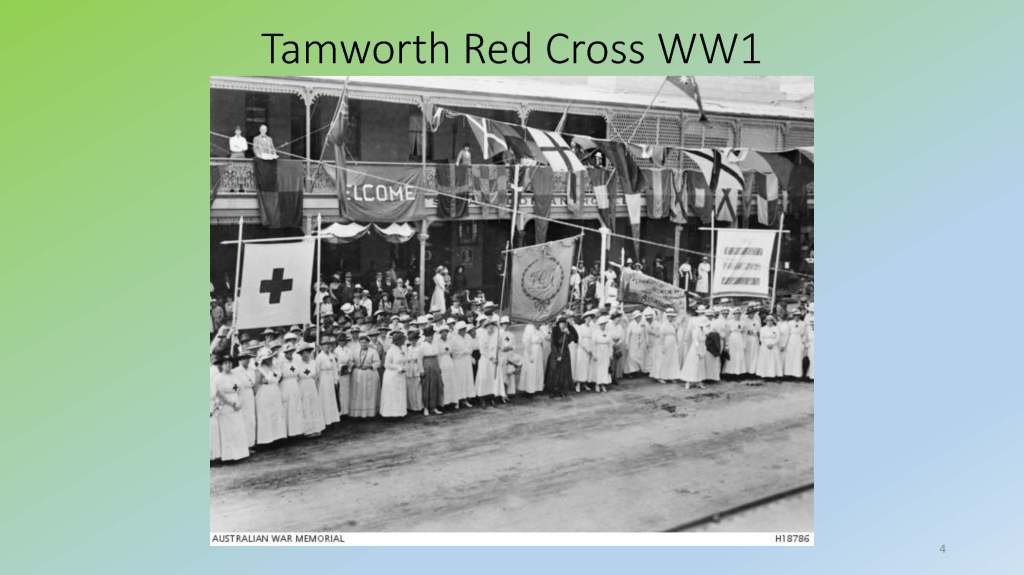

In the New South Wales Southern Tablelands country town of Goulburn, 150 women attended a meeting convened by Mrs Betts, the mayor’s wife, to form a local Red Cross branch. Those present recalled their efforts during the Boer War and immediately started Red Cross fundraising and organised a weekly sewing meeting at the Goulburn Guild Hall.[6] At Wellington in Western New South Wales, forty-five women attended a meeting convened by the mayor, T Kennard, and decided to form a Red Cross branch. They then collected £48 for Red Cross purposes.[7] In the New England area at Tamworth Mrs Green chaired a meeting of eighty women at the council chambers that established a Red Cross branch and drew on their Boer War experience.[8] In the Camden district, the first Red Cross branch was quickly followed by village branches at Menangle, Narellan, The Oaks, and later, Bringelly-Rossmore. By the Interwar period, the Camden Red Cross branch had become the largest in New South Wales, and district Red Cross activity extended to Voluntary Aid Detachments, the Junior Red Cross and Red Cross hospitals.

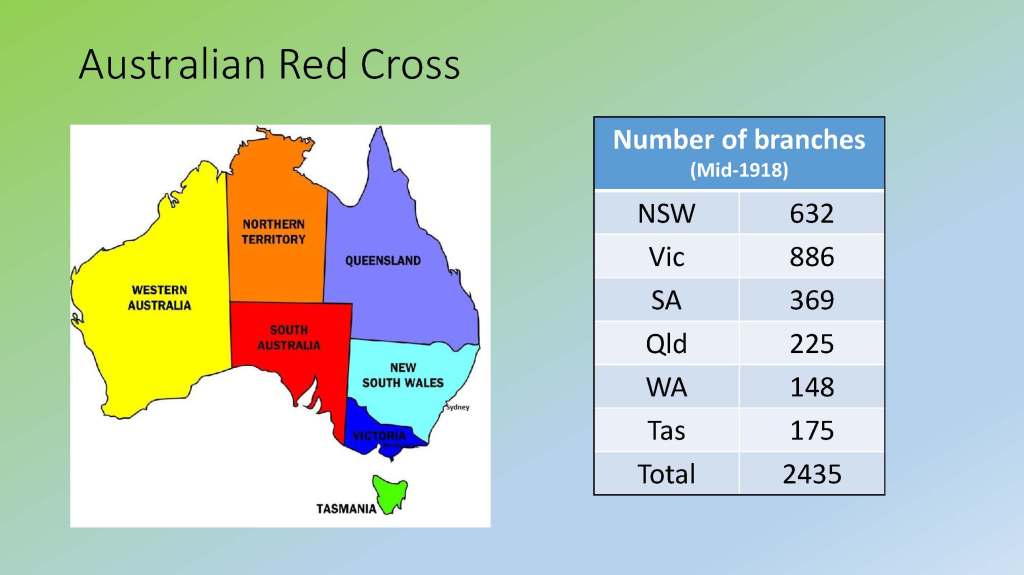

By mid-1918, there were 632 Red Cross branches across New South Wales, with country branches outnumbering city branches seven to one, with 45,800 registered members. Victoria had 886 branches in other states, South Australia 369, Queensland 225, Western Australia 148 and Tasmania 175. This made an Australian total of over 2,400 local branches from the country’s population of just over five million.[9]

The Australia Red Cross, which was initially a branch of the British Red Cross, was established with a three-tier structure, with the national council in Melbourne, six state divisions and local branches. During the First World War, the Red Cross headquarters was located in the Government House in Melbourne, under the watchful eye of Lady Helen Munro Ferguson. The national Red Cross was incorporated by Royal Charter in 1941, with the Governor-General as the national patron, while state governors are divisional patrons. The Australian Red Cross only became a truly national organisation in 2005 after much angst following sustained public criticism in 2003 around its fundraising activities.[10]

This paper argues that several over-riding themes dominated the local branches in the Red Cross movement during the First World War in Australia, and they were agency, service, motherhood and place. The story of the Australian Red Cross and its local branch network is a study of independent voluntary activism of conservative women in place. Women were empowered by joining the Red Cross, creating their own social space and gaining considerable social authority around wartime patriotic work with a national agenda. These women created what American historian Kathleen D McCarthy has called ‘parallel power structures’ where women forged an array of opportunities for themselves by gaining access to public roles, which provided ‘peaceful, gradualist change’.[11] The Red Cross provided opportunities for voluntary action for women across the social spectrum, especially in rural areas, that functioned within the tight familial and personal contact networks of small, closed communities. This type of voluntary activism did not challenge patriarchy, gender expectations, class, conservatism or Protestantism.[12]

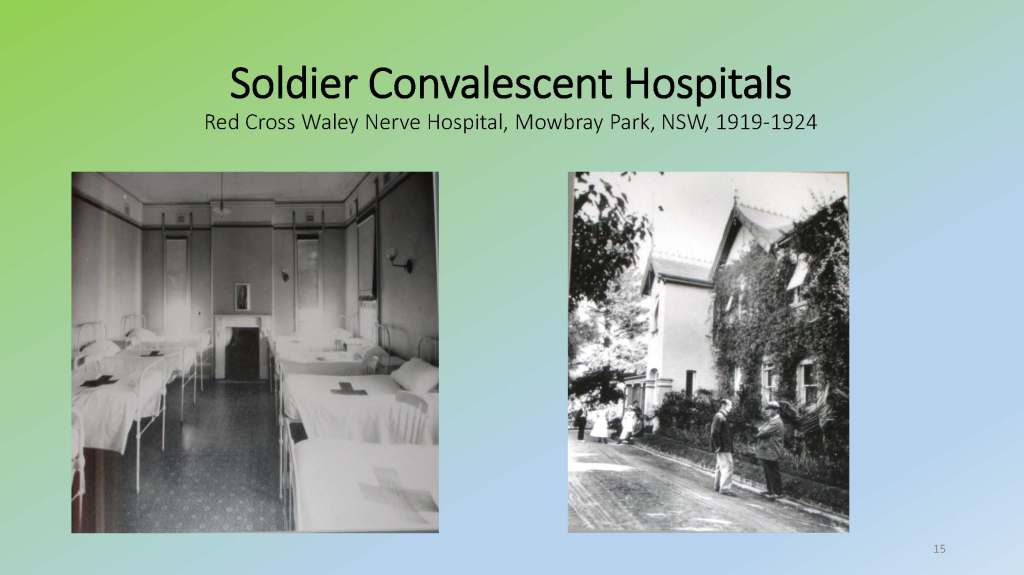

Training and efficiency were a hallmark of the Red Cross from its foundation. By the Interwar period, the society had absorbed aspects of modernism and the associated scientific principles linked with medical and social work. This was particularly evident in the Voluntary Aid Detachments, which were the paramilitary wing of the British Red Cross. First aid and home nursing training were prerequisites for men and women joining detachments in the 1880s in Great Britain. They were first registered with the Australian military in 1917. They were, according to historian Melanie Oppenheimer, to provide trained men and women in the Red Cross to nurse wounded soldiers in wartime.[13] During the First World War, voluntary aid provided a labour force to a variety of Red Cross convalescent and rehabilitation hospitals across the nation.

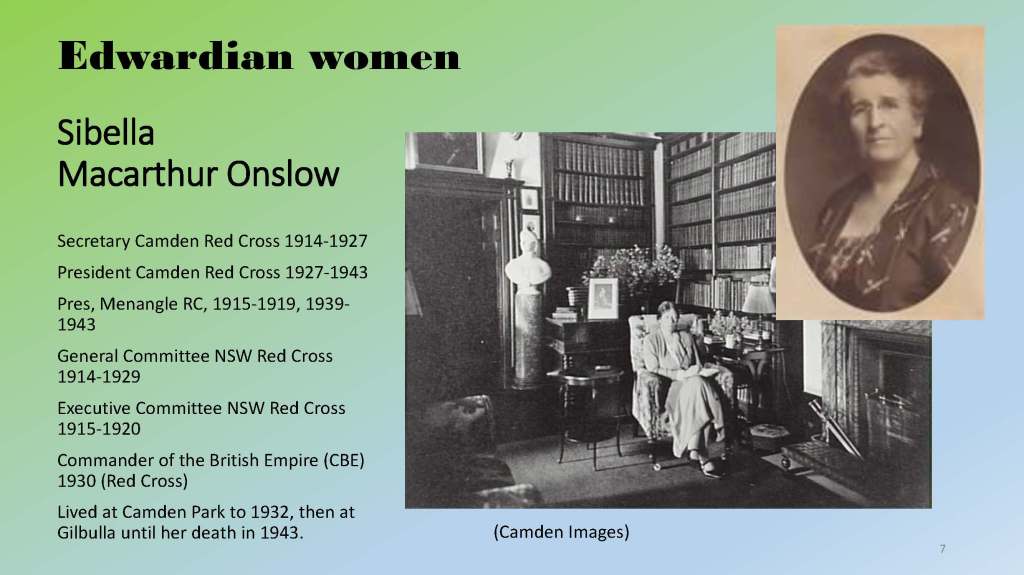

The Red Cross was a place-based activity with transnational links, led by intelligent, wealthy, powerful, conservative Edwardian women who were part of imperial networks that had an impact from the local branch to London. Australian women, like Sibella and Enid Macarthur Onslow of Camden Park, copied the example of Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, who saw social action in the Red Cross as an alignment of patriotism, duty, class, gender, Christianity and motherhood. These women, committee members of the New South Wales divisional Red Cross and the national body in Melbourne, understood that the Red Cross in Australia successfully captured the essence of place by organising locally and advocating nationally. Red Cross branches and their wartime patriotic activities significantly contributed to developing community identity and a sense of place. Red Cross organisers understood the nature of parochialism and how it was an extension of a highly formalised sense of community revolving around social obligation and reciprocity. Red Cross branches were a form of self-help through neighbourly assistance and mutuality. The branches provided a source of close and positive social interaction in a time of crisis, according to Canadian historian Elizabeth Kenworthy Teather. She has demonstrated how the stories of place are intimately linked to family and friends, the values and traditions they fostered and people’s ability to express their attachment to place.[14]

Red Cross branches helped maintain morale within the community and allowed individuals to do ‘their bit’ for the war effort through patriotic activities and fundraising. For those on the homefront, being patriotic meant supporting ‘their boys’ from ‘their community’, and not doing so was seen as being unpatriotic. The branches helped develop a sense of community through close bonds of identification around the construction of place where intimacy, parochialism and localism created a closed community. Wartime homefront activities for the Red Cross contributed to people’s experience, loyalty to an organisation and their story of attachment to place. The stories of women’s families are embedded in the landscape, reflected in their heritage, memories, celebrations, rituals and ceremonies, and are the essence of place.

Red Cross authorities promoted the society to volunteers and the community as the soldier’s metaphorical ‘mother’ and guardian angel on the battlefield. The mother metaphor was used in the Red Cross Record as early as December 1914 in an article called ‘Mothers of Men’.[15] The ‘guardian angel’ metaphor appeared in Australian newspapers in August 1914 when the Sunday Times (Sydney) called Red Cross volunteer workers ‘Angels of Mercy’, and Red Cross nurses had ‘the touch of Christ’.[16] Earlier in the year, Lady Helen Munro Ferguson had referred to Red Cross workers using the Biblical allusion to ministering angels.[17] By 1918, the metaphor of the Red Cross as an angel was well entrenched, and the Hobart Mercury ran a story about the Red Cross under the heading of ‘A Ministering Angel’ while in Adelaide, the Register published an article under the headline ‘The Ministering Angel, Tribute to Red Cross Work’.[18] By 1918, the Red Cross was identified in the English-speaking world in posters and other publicity as the ‘Red Cross, Mother of all Nations’ and the ‘Greatest Mother in the World’.[19] The work of Canadian historian Sarah Glassford has shown how these features also characterised the American and Canadian Red Cross. The role of the fictive mother was not new, as American historian Ellen Ross noted when the Women’s Labour League was assigned the mother’s role towards British children at a 1912 conference by a volunteer doctor.[20]

The Red Cross as mother and guardian angel was an extension of the notion around the ideology of motherhood and the anxieties about declining birth rates across the Empire in settler societies. Motherhood was seen as a national duty [21]. It was linked with concerns over the decay of the home and family life by several women’s groups, especially those associated with evangelical Christianity. They included the Mothers’ Union, the National Council of Women, and later the Women’s Institutes, the Country Women’s Association in Australia and the Red Cross. The Red Cross encouraged local branch volunteers, mostly women, to immerse themselves in the ministering angel mythology and serve ‘their boys’ by volunteering as Red Cross workers for God, King and Country throughout the First and Second World Wars. The concerns of Edwardian women were overwhelmingly centred on the family, home and their religion. Australian historians Marian Quarterly and Judith Smart have called this maternal feminism and have maintained that it was the justification for women’s entry into public life.[22]

I would argue that the ministering angel’s metaphor was a mix of femininity combined with notions of patriotism and service, discipline and training, motherhood and purity, stoicism and selflessness, all wrapped up in events surrounding war and death. The Red Cross, as mother and guardian angel, was the expression of moral purity and Christian charity in the face of war’s violence, destruction and devastation. This symbolism was still used by the Australian Red Cross in the 1990s. The Red Cross worker as a mother figure and guardian angel paralleled a similar narrative associated with the nursing profession and the Australian male Anzac legend, which developed during the First World War. Much of the rhetoric that emerged around the themes of motherhood and the ministering angel was based on a type of biological determinism that maintained that ‘nurturing was more natural for women and viewed aggression as inherently male’.[23]

From the outset of the Red Cross in 1914, volunteering had a practical purpose and fits Hilary M Cary’s ideology of ‘female collectivism’ where women believed in ‘collective action as a force for change’.[24] More than this, Edwardian women were interested in organisations that had visible results, efficiency, attention to detail, and were personal. According to Julia Bush, the Red Cross fitted the purpose.[25]

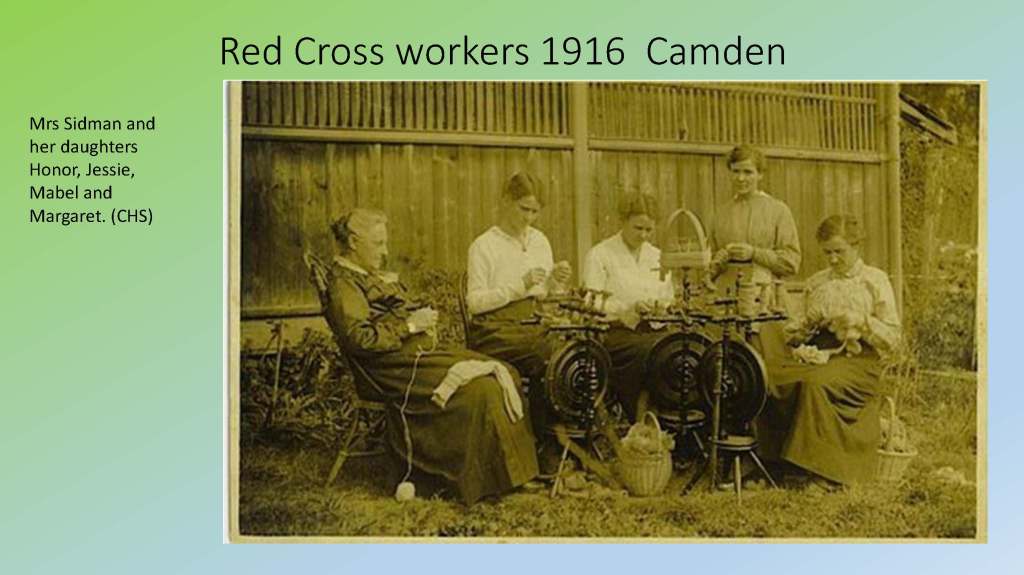

Practical Red Cross work with a purpose was an extension of women’s domesticity, and Red Cross workers developed their own spaces through sewing and knitting activities. Australian historian Emma Grahame has called these ‘semi-public/semi-domestic spaces’ which empowered women through their agency and charity work. Women were ‘cultural producers’ undertaking an activity that did not conflict with their commitment to their family or, according to Grahame, their cooperative styles or their practical, intuitive working methods.[26]

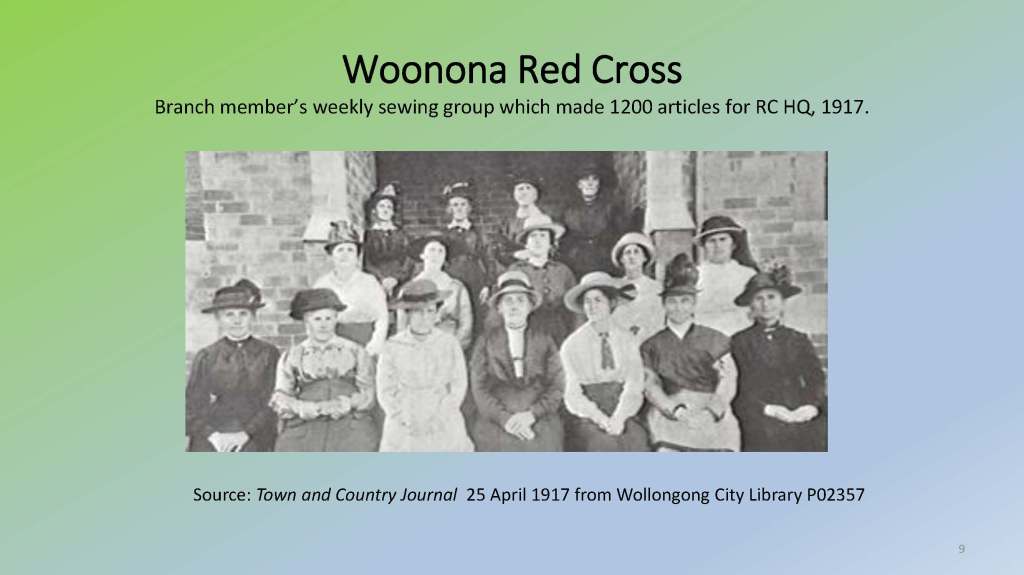

Local Red Cross branches set up sewing circles in local halls in a quasi-industrial production line setting. At Berry on the New South Wales South Coast, Red Cross workers held weekly sewing circles and made shirts, balaclava caps, flannel belts, cholera belts, mufflers, towels and pillowcases, and other items. Between 1914 and 1919, the Berry Red Cross workers made over 6,600 articles that were sent to the headquarters of the Sydney Red Cross. Local branches gave regular updates on their sewing efforts in the country press. In the Victorian Goldfields town of Ballarat, Mrs McDonald, the secretary of the Ballarat Red Cross, reported on their efforts at the 1915 June meeting. One pair of socks had been received from Miss Tanner, Mrs Eyres, and Mrs Williams, while Mrs Ross supplied seven pairs, Miss Turner six pairs, and Mrs Walker had made one flannel shirt, one pair of socks and one washer, Miss Nicholls thirteen pairs of slippers and Miss Parker had made twenty-six washers. In total, over eighty-five individual women had hand-made socks, shirts, washers, slippers, pyjamas, scarves, bandages, cholera belts, caps and other articles.[27]

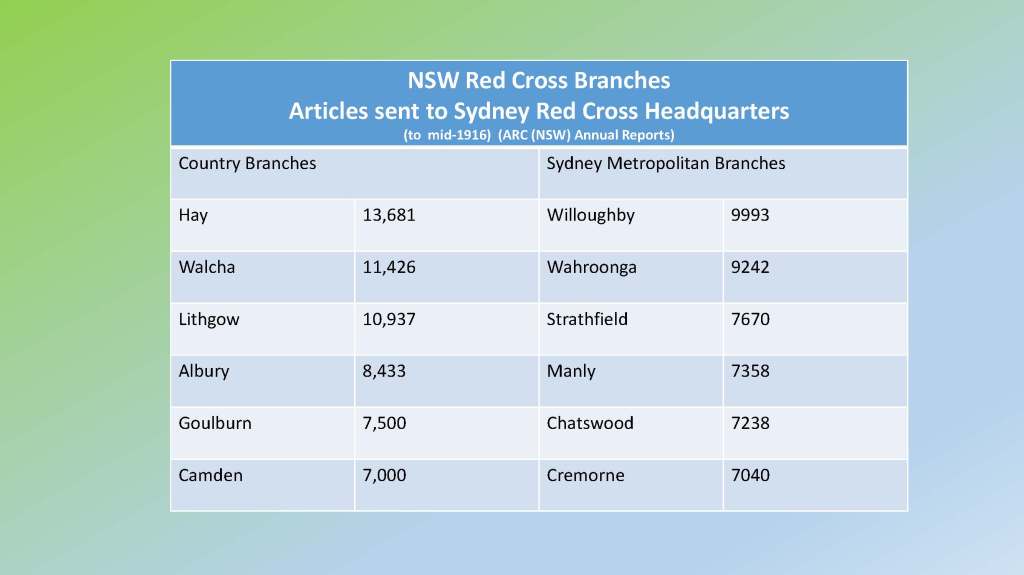

According to historian Bruce Scates, Red Cross branches made a considerable effort, and Red Cross work involved an enormous amount of ‘emotional labour’.[28] Up to mid-1916, country branches supplied more to Red Cross headquarters in Sydney than metropolitan branches. Casino Red Cross topped the state with 17,990 items, followed by Hay Red Cross with 13,681 articles, Walcha with 11,436, then Lithgow with 10,937, Goulburn with 7,500, while in the Sydney Metropolitan Area, Vaucluse Red Cross supplied 10,100 individual items, Willoughby Red Cross sent in 9993 articles, at Manly 7,358, and Wahroonga 9242. By the war’s end, women at Hay in Western New South Wales had sent in over 30,000 articles, while in the Camden district, Red Cross workers had supplied around 20,000 articles to Red Cross headquarters.[29]

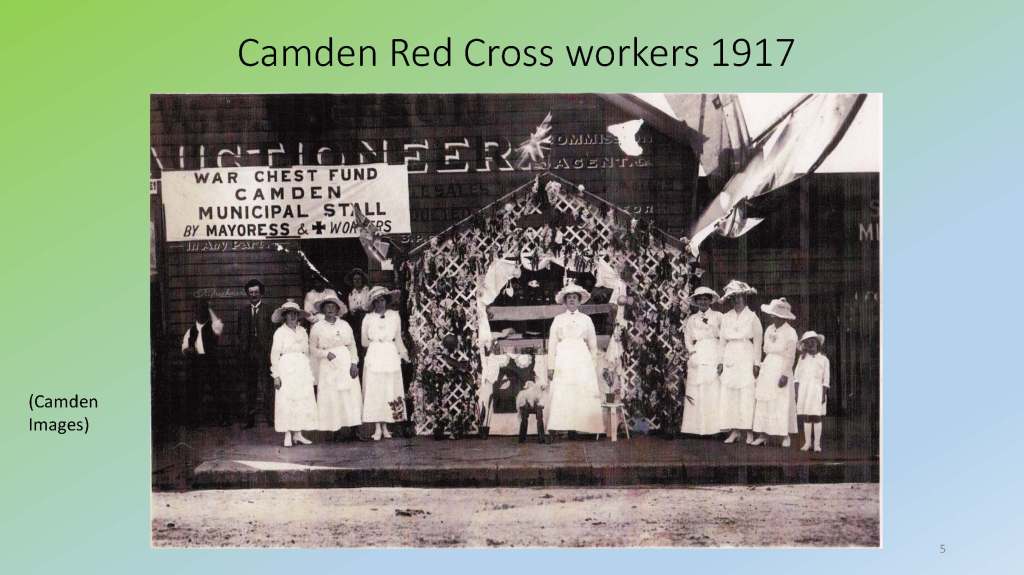

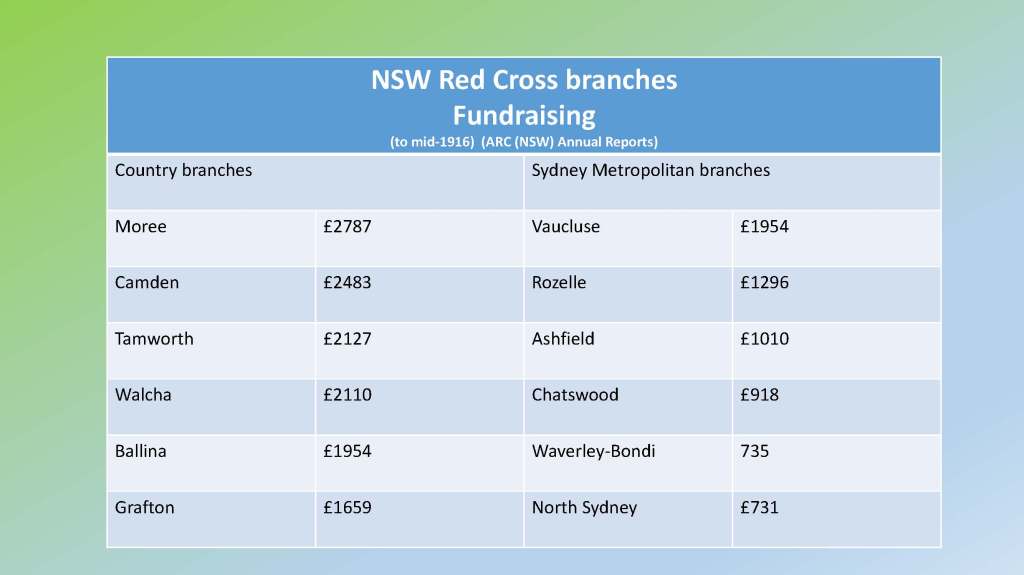

Red Cross work making hospital supplies required a strong cash flow, as Lady Helen Munro Ferguson had foreshadowed in 1914, and branches embarked on patriotic fundraising. Activities included all the traditional forms that many of these women undertook on church committees, such as stalls, fairs, gymkhanas, raffles, donations, and other activities. Various community organisations also provided Red Cross branches with considerable financial support. At the same time, Red Cross workers used their social networks to leverage additional community support, especially in rural areas. Consequently, rural branches rose higher than city suburban branches. The most successful fundraising efforts across New South Wales up to mid-1916 were country branches at Moree Red Cross raised £2,787, Camden £2,483, Tamworth £2127, Walcha £2,110 while the most successful branches in the Sydney Metropolitan Area were Vaucluse £1,954, Rozelle £1,296, and Ashfield £1,010.[30]

The sewing and fundraising efforts of Red Cross branches were sent to Red Cross headquarters in Sydney, which then provided supplies to a range of military hospitals in Australia and overseas, as well as Red Cross convalescent and rehabilitation hospitals. In 1916, the New South Wales Red Cross was responsible for seven military hospitals and 22 field and camp hospitals in New South Wales alone. By 1918, the New South Wales Red Cross managed and financed eight hospitals, 19 convalescent homes, and 4 sanatoria for soldiers suffering from tuberculosis.

In conclusion, since the outbreak of the war in 1914, Australian women have used their Boer War experiences and participated in independent voluntary activism across Australia by setting up Red Cross branches. The place-based nature of Red Cross work was an extension of the women’s private space where their concerns centred on family, church and community. The Red Cross used the allegory of motherhood, wrapped up with notions of Christian charity, to encourage women’s participation. Women used their domestic skills from the private sphere and became Red Cross workers sewing, knitting and fundraising for patriotism to support ‘their boys’ in patriotic housekeeping. Red Cross volunteering became synonymous with matters of soldier welfare and national patriotism. Fundraising became a significant community event, where parochialism was linked to national wartime priorities, and by 1918, many local Red Cross branches had effectively controlled most of the homefront war effort. Voluntarism allowed women, particularly those in closed rural communities, to create parallel paths for themselves within tightly controlled social networks in the form of maternal feminism. The study of Red Cross branches is one example of a local study that can provide a window into the broader national picture.

Notes

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 July 1911.

[2] Margaret Fitzherbert, Liberal Women Federation to 1949, Federation Press, Sydney, 2004, pp 25-27.

[3] The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 May 1911.

[4] NSW Division, ARCS(BRCS), Annual Report 1914, p.4

[5] The Ballarat Courier, 11 August 1914. The Ballarat Star, 12 August 1914. The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate (Parramatta), 12 August 1914. The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 August 1914.

[6] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 15 August 1914.

[7] Wellington Times, 20 August 1914.

[8]The Tamworth Daily Observer, 13 August 1914.

[9] Melanie Oppenheimer, The Power of Humanity, 100 Years of Australian Red Cross 1914-2014, Harper Collins, Sydney, 2014, p. 26. NSW Division, ARCS(BRCS), Annual Report 1917-1918, p 36.

[10] Oppenheimer, The Power of Humanity, pp 248-258.

[11] Kathleen D McCarthy, ‘Parallel Power Structures: Women and the Voluntary Sphere’, in Kathleen D McCarthy, ed, Lady Bountiful Revisited, Women, Philanthropy and Power, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1990, pp 1,11, 23

[12] Ian Willis, ’Wartime volunteering in Camden’, History Australia, 2004, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2004, p. 5.

[13] Melanie Oppenheimer, Red Cross VAs, A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales, Ohio Productions, Walcha, 1999, pp 3-5. The NSW Red Cross Record, Volume 13, Issue 7, 2 July 1917, p 15.

[14] Elizabeth Kenworthy Teather, ‘Voluntary Organizations as Agents in the Becoming of Place’, The Canadian Geographer, Volume 41, Issue 3, 1997, pp. 226-34. Elizabeth Kenworthy Teather, ‘The double bind, being female and being rural: a comparative study of Australia, New Zealand and Canada’, Rural Society, Volume 8, Issue 3, 1997, p 215.

[15] The NSW Red Cross Record, December 1914, p 19.

[16] Sunday Times (Syd), 30 August 1914.

[17] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 July 1914.

[18] The Mercury (Hobart), 23 April 1918. The Register (Adelaide), 12 July 1919.

[19] National Library of Australia, War Posters, Lithographs, 1918.

[20] Sarah Glassford, “The Greatest Mother in the World”, Carework and the Discourse of Mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War’, Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008, pp 219-232. Ellen Ross, ‘Good and Bad Mothers: Lady Philanthropists and London Housewives before the First World War’, in Kathleen D McCarthy, ed, Lady Bountiful Revisited, Women, Philanthropy and Power, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1990, p 182.

[21]. Anna Davin, ‘Imperialism and Motherhood’, History Workshop, Volume 5, Issue 1, 1978, p13.

[22] Marian Quarterly and Judith Smart, Respectable Radicals, A History of the National Council of Women of Australia 1896-2006, Monash University Publishing and National Council of Women of Australia, Melbourne, 2015, pp 53-54.

[23] John Connor, Peter Stanley and Peter Yule, The War at Home, Volume 4, in series The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2015, p 182.

[24] Hilary M Cary, ‘”Doing Their Bit”: Female Collectivism and Traditional Women in Post-Suffrage New South Wales’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, Volume 1, Issue 2, 1996, pp 101, 108-109.

[25] Julia Bush, Edwardian Ladies and Imperial Power, Leicester University Press, London, 2000, p 74.

[26] Emma Grahame, “Making something for myself”: women, quilts, culture and feminism, PhD Thesis, UTS, 1998, pp 9, 92-95.

[27] The Ballarat Courier, 19 June 1915.

[28] Bruce Scates, ‘The unknown sock knitter: voluntary work, emotional labour, bereavement and the Great War’, Labour History, Issue 81, November 2001, p 31.

[29] NSW Division, ARCS(BRCS), Annual Report 1914-1916. The Riverine Grazier, 28 March 1990.

[30] NSW Division, ARCS(BRCS), Annual Report 1914-1916.

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.