Australian Historical Association 33rd Annual Conference

Conflict in History

University of Queensland

7-11 July 2014

Abstract

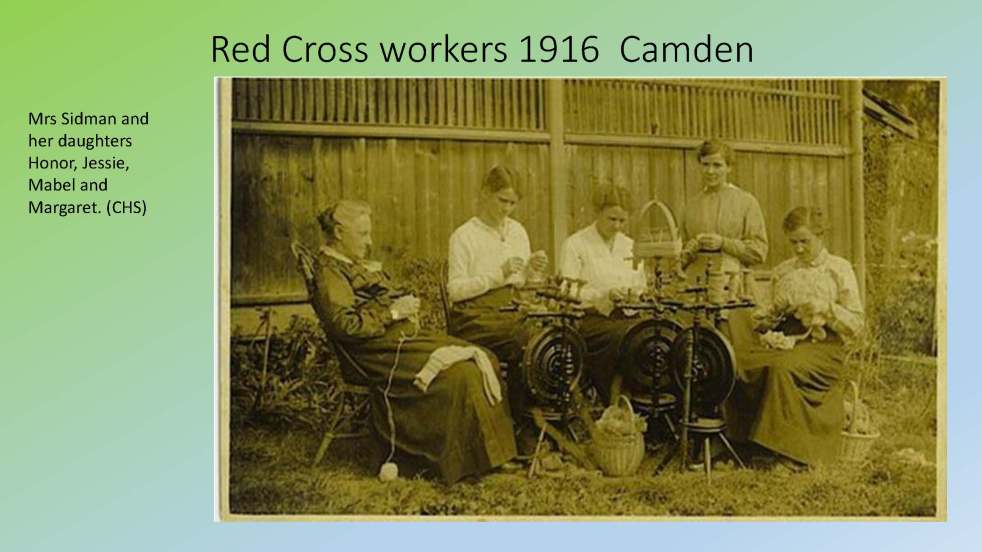

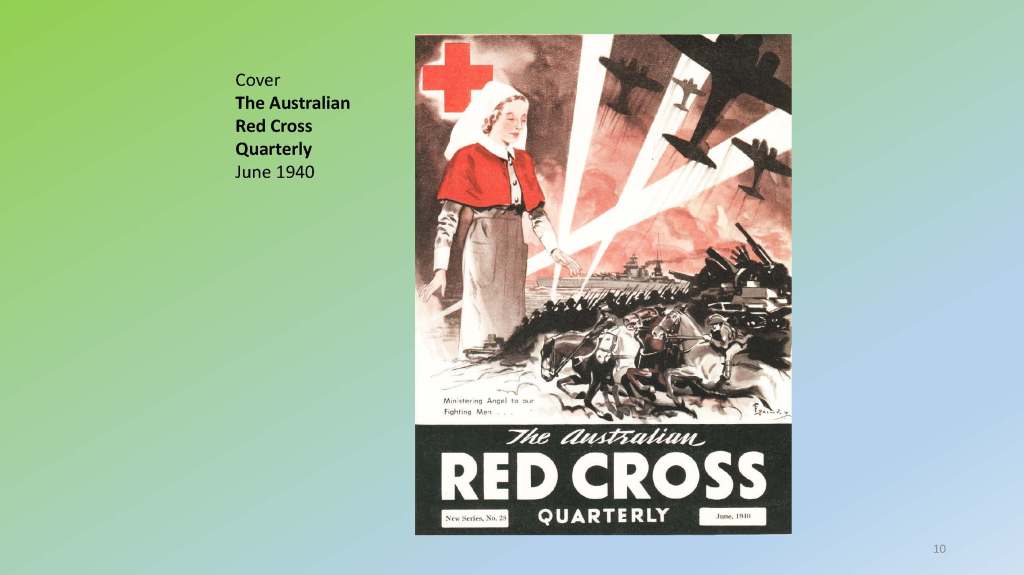

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 saw thousands of women across rural Australia set up local Red Cross branches. Country women sewed, knitted and cooked for God, King and Country, while they were encouraged to see themselves as ‘ministering angels’ dutifully serving ‘their boys’ and the imperial cause. Their successes meant that by 1918, they owned the story of the homefront war effort in many localities. Was this a spontaneous outbreak of patriotic voluntarism by country women, and who benefitted from the incredible homefront success of the Red Cross?

Slide Presentation

Paper

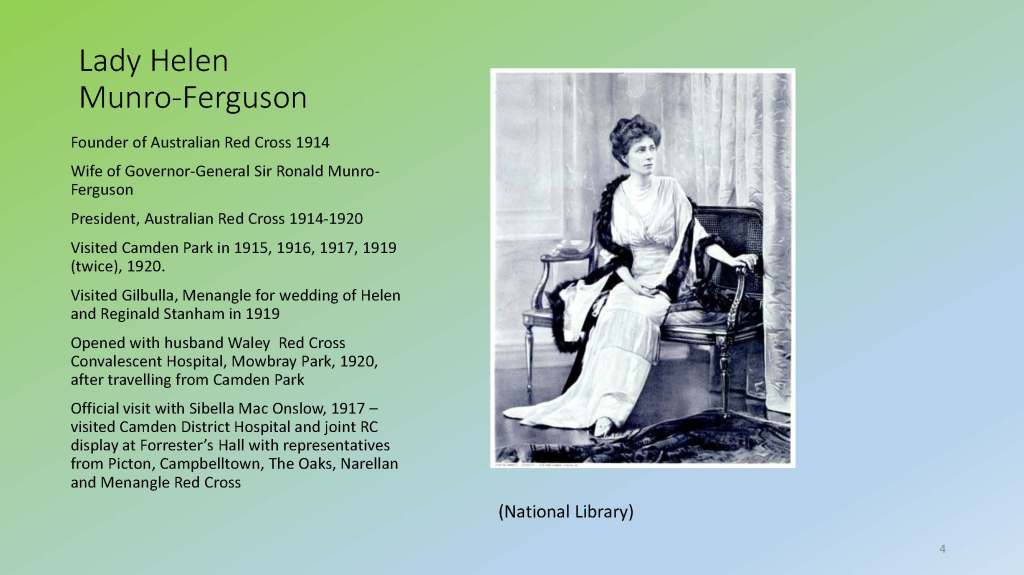

From a standing start in August 1914, when Lady Helen Munro Ferguson launched the Red Cross at the outbreak of the war, by the end of 1915, there were 357 branches across New South Wales, 272 country branches, and 85 metropolitan branches. By the end of the First World War, this had increased to 632 branches across New South Wales, of which there were 550 country branches and 82 suburban branches, with a registered membership of 46,000.

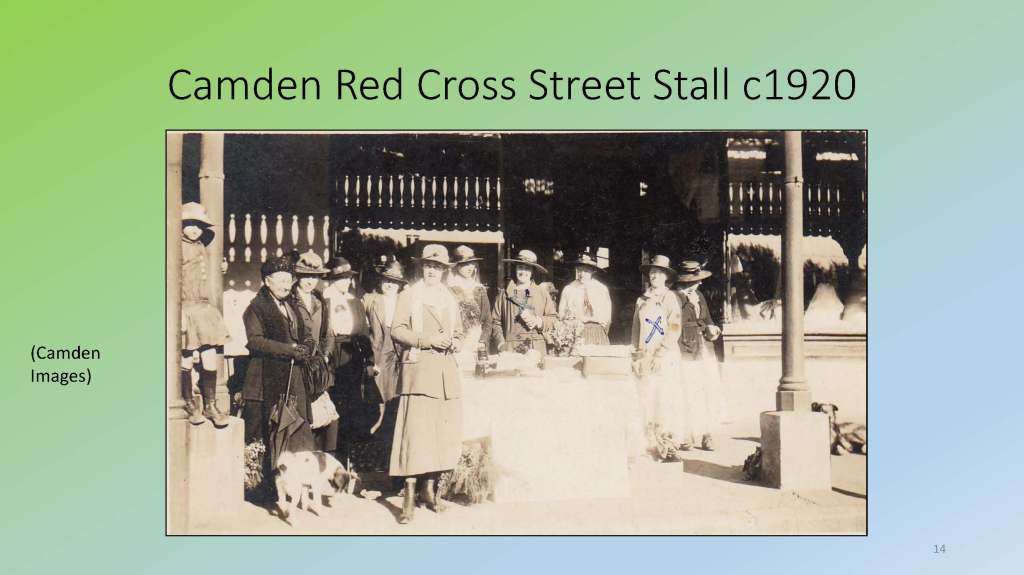

As these numbers suggest, the Red Cross Society was one of rural Australia’s most important voluntary organizations. It has characterised the voluntary sector in country towns and villages and become integral to their social and cultural traditions. The Red Cross was born in New South Wales in wartime, and stories of places around Red Cross activities on the wartime homefront have shaped community identity and the construction of a place. In many parts of the state, wartime patriotism and Red Cross work became synonymous with matters of soldier welfare through the traditional arts of sewing, knitting and cooking. Fundraising for the Red Cross became a major community activity, where parochialism was married to national wartime priorities.

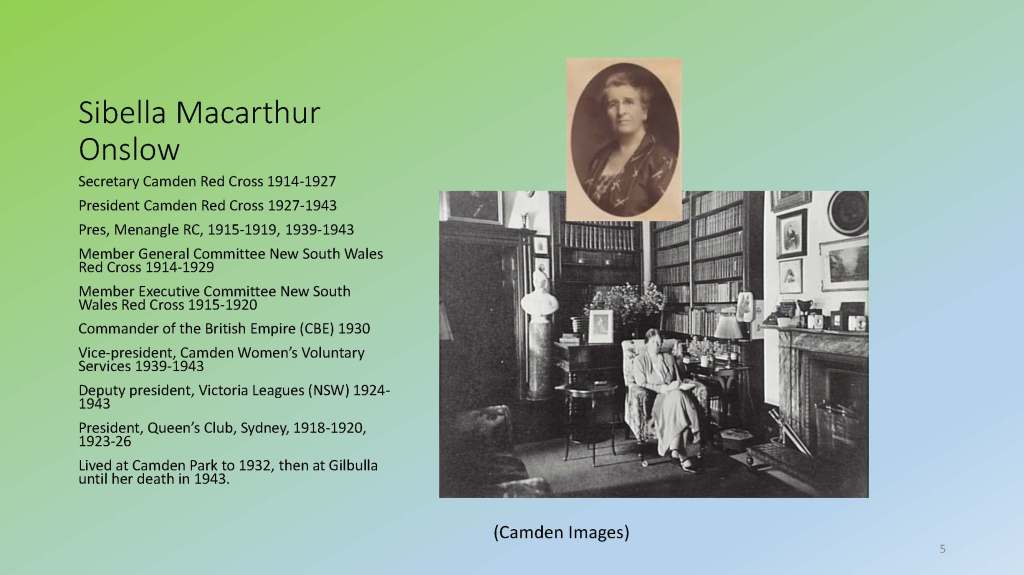

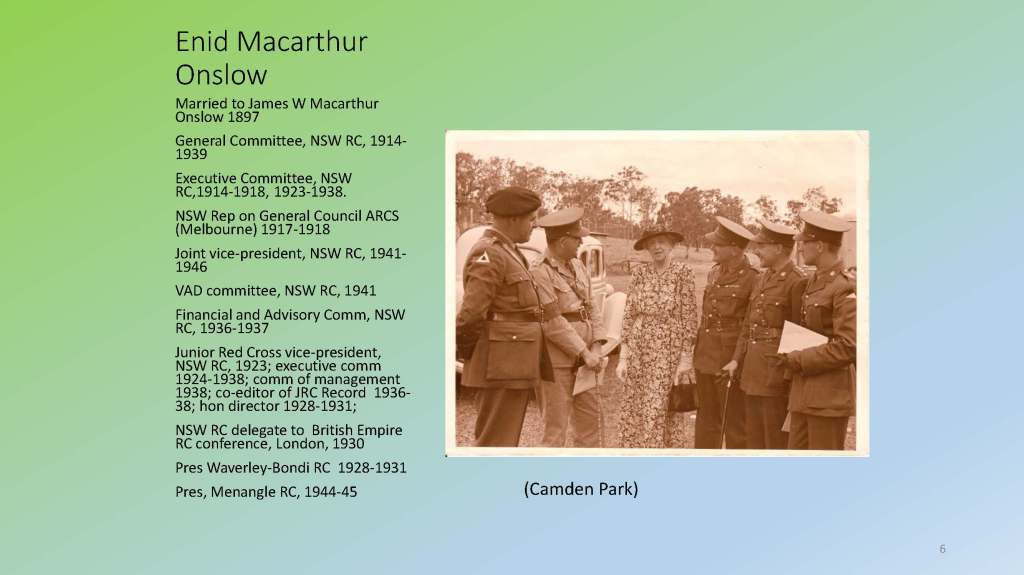

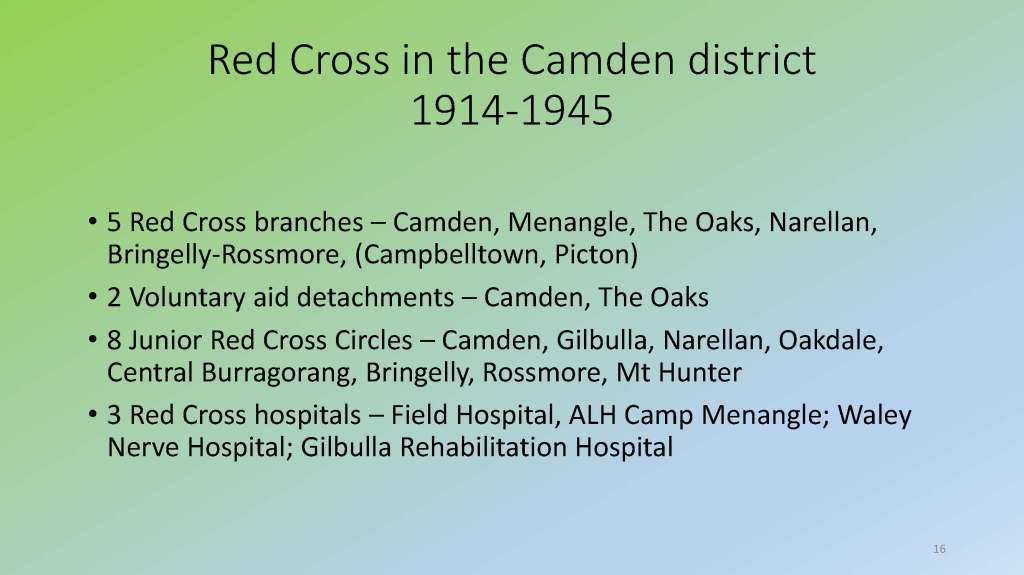

This paper is part of a larger project on the Camden District Red Cross. It is a local study, which is not common in studies of the Australian Red Cross. In the towns and villages of the Camden district, community support for the Red Cross was driven by the same desire to alleviate suffering on the battlefield, which was instrumental in the formation of society. The first district Red Cross branch was established at Camden in the days after the founding of the national Red Cross and was quickly followed by village branches at Menangle, Narellan and The Oaks. By the inter-war period, the Camden branch had become one of the largest in New South Wales, and district Red Cross activity extended to Voluntary Aid Detachments, the Junior Red Cross and Red Cross hospitals. District Red Cross leadership was marked by its exclusivity and centred on the Macarthur women of Camden Park, one of Australia’s most important colonial estates, and their transnational linkages between Camden, Sydney, Melbourne and London. Red Cross work reinforced their conservatism, yet it provided groundbreaking opportunities for the agency and empowerment of other district women.

Service, motherhood and place

The Camden District Red Cross story is a local study about the voluntary activism of conservative country women in place. They were empowered by joining the Red Cross, creating their own social space and gaining considerable social authority around wartime patriotic work with a national agenda. The Red Cross was a place-based activity with transnational links, led by intelligent, wealthy, powerful conservative women who were part of imperial networks that had an impact from Camden to Sydney, Melbourne and London. Camden women embraced the Red Cross in 1914 because it encapsulated their cultural values and traditions, which were represented by Britishness, patriotism, service, and Christian charity in locations across the district. In rural Australia, the Red Cross, and before that, church committees, had provided opportunities for voluntary action for educated middle-class women who functioned within the tight familial and personal contact networks of small, closed communities. This type of voluntary activism did not challenge patriarchy, gender expectations, class, conservatism or Protestantism.

[1] Training and efficiency were a hallmark of the Red Cross from its foundation in the VAD movement. By the inter-war period, the society and other women’s organisations had absorbed aspects of modernism and the associated scientific principles linked with medical and social work.

Camden’s Edwardian women, Enid Macarthur Onslow, Sibella Macarthur Onslow and their ilk, saw social action as an alignment of patriotism, duty, class, gender, Christianity and motherhood. After 1914, the Red Cross leadership at all levels of the organization wrapped these characteristics together. It promoted the society to volunteers and the community as the soldier’s metaphorical ‘mother’ and guardian angel on the battlefield. Melanie Oppenheimer identified the mother metaphor in Red Cross literature as early as May 1916.[2] The Red Cross was identified in posters and other publicity as the ‘Red Cross, Mother of all Nations’ and as the ‘Greatest Mother in the World’. [3] Kate Egan, the organizer of the packing department of the New South Wales Red Cross, maintained that the Red Cross was ‘stretching forth her hand to all in need…[s]he’s warming thousands, feeding thousands, healing thousands from her store, the greatest mother in the world’. In 1919, the Brisbane Courier ran an article in Red Cross Week under the heading ‘The Mother of Soldiers’ and felt that the Red Cross was ‘the great mother who stretches forth her hands to all in need, warming thousands, feeding thousands, healing thousands from her store’. A ‘Soldier’s Mother’ wrote in 1918 that the ‘Red Cross is the greatest mother in the world, stretching forth her hands to all in need’. A Sydney Morning Herald correspondent called the Red Cross ‘the great soldier’s mother’. On Red Cross Button Day in 1918, the three designs for sale for 1/- were ‘The Greatest Mother in the World’ , ‘The Soldiers’ Friend’ and an image of a Red Cross nurse with an outstretched hand’.[4] Mary McAnene, who was a nurse at No 3 Australian General Hospital at Lemnos and matron of Camden District Hospital before joining up, maintained that

It would be a sorry day for the boys when they get their knock if it were not for the Red Cross; the military authorities are like a father to the lads, but the Red Cross is like their mother.[5]

According to historian Anna Davin, the Red Cross as mother and guardian angel was an extension of the notion around the ideology of motherhood, which was an integral part of women’s service role in the British Empire. The ideology of motherhood stated that women had the duty and destiny to be the ‘mothers of the race’. Child-rearing was a national duty, and good motherhood was an essential component in the (eugenists) ideology of racial health and purity. The family was the basic institution of society, and women’s domestic roles remained supreme. By the inter-war period, pre-occupation with the family and motherhood had turned these traits into a national priority for the British race. Imperial motherhood was promoted as a scientific necessity and a patriotic duty.[6] There were concerns over the decay of the home and family life expressed by several British women’s groups, especially those associated with evangelical Christianity, including the Mothers’ Union (MU), the National Council of Women, and later the Women’s Institutes, the Country Women’s Association (CWA) and Red Cross. These voluntary organisations provided a training ground for middle-class women. They allowed them to gain a ‘public persona’ while upholding the ‘values of both middle-class femininity and bourgeois respectability’.[7] This became one of the principal wartime roles of the Camden Red Cross. Even today, journalist Helen McCabe maintains that the conservatism of Australian women is based on their nurturing role of women as mothers. [8]

The metaphor of the mother figure and the ministering angel was used on the cover of the Red Cross Quarterly in June 1940 and elsewhere for publicity and fundraising purposes (cover plate). The spiritual mystique of the ministering angel was a mix of the Victorian construction of femininity combined with notions of patriotism and service, discipline and training, motherhood and purity, stoicism and selflessness, all wrapped up in events surrounding war and death. The imagery positioned the angel hovering over the battlefield as a mother figure looking out for the wounded soldiers. These images were a powerful psychological tool in the hands of Red Cross women who understood how to extract maximum benefit from their use. The Red Cross, as mother and angel, was the expression of moral purity and Christian charity in the face of war’s violence, destruction and devastation. Even in 1995 the Red Cross used the same type of imagery on publicity material for its annual winter appeal.

The Red Cross worker as a mother figure and ministering angel is best represented by the work of the women who joined Voluntary Aid Detachments. According to Melanie Oppenheimer, Voluntary Aids (VAs) ‘encapsulated the mythical role of “the Goddess of Peace”‘[9] and earned this reputation by undertaking duties, such as that on HMS Glory in 1945 during prisoner of war repatriation trips from Southeast Asia to Australia. The mythology paralleled a similar narrative associated with the nursing profession[10] and the male Anzac legend, as both developed during the First World War. Red Cross workers and VAs were romantic images of duty and self-sacrifice in their patriotic service to the British Empire. In particular, the uniformed VAs displayed mateship, camaraderie, strength of character, endurance, loyalty, courage and sacrifice, all of which are part of the male Anzac legend.[11] Other characteristics typical of the VAs could be described as stereotypically feminine, including purity, virginity, kindness, softness, caring, emotion, affection, warmth, protection, spirituality, and altruism. Lady Galleghan (Persia Elspeth Porter), who was assistant commandant of the New South Wales VADs at the end of the Second World War, felt that the VAs ethos combined notions of ‘service’, ‘patriotism’, ‘training’, ‘character’ development and ‘friendship’[12] coupled with the Victorian construction of femininity.

The Red Cross encouraged Camden women to immerse themselves in the ministering angel mythology and serve ‘their boys’ by volunteering as Red Cross workers for God, King and Country throughout the First and Second World Wars. The values and traditions expressed by the Red Cross appealed to conservative country women, and it is no surprise that many were attracted to voluntary action for the movement. The Red Cross typified Hilary Cary’s ideology of ‘female collectivism’, where women believed in ‘collective action as a force for change’. Cary’s ideology states that traditional women formed voluntary organisations with a conservative emphasis on ‘non-party, non-sectarian voluntary activity [that supported] the welfare of their own communities’, which Cary maintains was code for non-Labor and Protestant. The Macarthur Onslow women and others were Cary’s women ‘who were active in community-based service and church organizations in the post-suffrage years’. Conservative women’s organizations benefitted members of the ‘needy’ from their communities through the ‘provision of practical programs of good work’, and Red Cross branches provided an ideal vehicle by supporting soldier, and later civilian, welfare. For these women, practical programs had visible results, efficiency, and attention to detail and were personal in nature.[13]

By 1918 Camden District Red Cross branches helped maintain morale within the community and allowed individuals to do ‘their bit’ for the imperial war effort through patriotic activities and fundraising. For those on the homefront, being patriotic meant serving God, King and Country by supporting ‘our boys’ from ‘our community’; not doing so was seen as unpatriotic. ‘Our boys’ included women’s husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, cousins and uncles. Red Cross branches helped develop a sense of community through close bonds of identification around the construction of place where intimacy, parochialism and localism created a closed community. These communities were hostile to outsiders who did not have the patriotic interests of the local community at the centre of their activities. Wartime homefront activities for the Red Cross contributed to people’s experience, loyalty to an organisation and their story of attachment to place. The conservatism of Camden women was not radical and concerned with their family, children, marriage, home life and community.

Conclusion

By 1918, the homefront patriotic effort of Camden Red Cross workers had raised £3700, which was divided between £1450 for Red Cross purposes and £2250 for Australian patriotic funds. Other district village branches raised £670, giving a district total of £4400. Compared with the weekly minimum wage for a farm labourer with keep, which was £2/2/-, every working male in the Camden district donated the equivalent of one week’s wage to Red Cross causes. Camden district Red Cross workers had made around 20,000 comfort items from 40,000 hours of unpaid voluntary service, and other village branches had about 10,000 garments, which took about 20,000 hours of effort. They dominated the homefront war effort in these small country towns.

So, who benefitted from this effort:

- Camden soldiers had received considerable support along with the national Red Cross’s patriotic effort

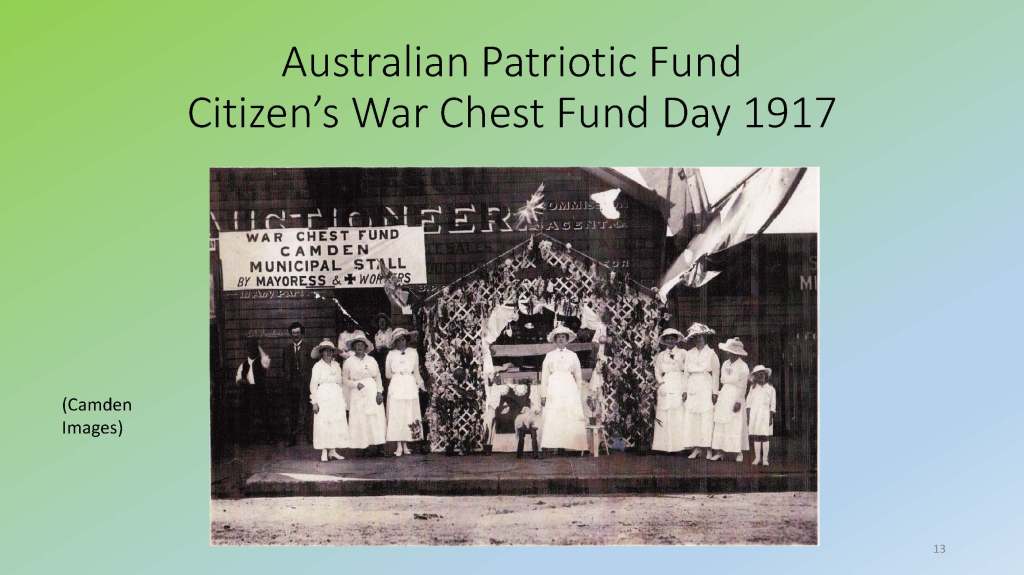

- The Camden district Red Cross supported several Australian Patriotic funds, including Citizens’ War Chest, Jack’s Day, Australia Day, Frances Day, and others.

- The Australian Government had benefitted from the efforts of Red Cross volunteers as a form of voluntary taxation.

- Female gentry across the Camden district had re-enforced their social position and moral authority.

- Middle-class women had found a constructive outlet for their patriotism

By 1918, the Camden District Red Cross effectively controlled most of the homefront war effort.

Notes

[1] Ian Willis, ’Wartime volunteering in Camden’, History Australia, Vol 2, No 1, 2004, p5.

[2] Red Cross work in NSW. A Souvenir of the Great War. Supplement in the Red Cross Record May 1916, p9. Cited Melanie Oppenheimer, All Work No Play, Australian Civilian Volunteers in War, Walcha, NSW: Ohio Productions, 2002, p.43. f.30

[3] National Library of Australia, War Posters, Lithographs, 1918.

[4] The Camden News, 19 September 1918. The Brisbane Courier, 26 July 1918. The Blue Mountain Echo, 19 July 1918. The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 1919. The Mail (Adelaide), 7 September 1918

[5] The Camden News, 27 June 1918

[6]. Anna Davin, ‘Imperialism and Motherhood’, History Workshop, (1978) 5 (1): 9-66. DOI: 10.1093/hw/5.1.9, p.13.

[7]. Clare Wright, ‘Of Public Houses and Private Lives, Female Hotelkeepers as Domestic Entrepreneurs’, Australian Historical Studies, v.32, no. 116, April 2001, p. 69.

[8] Richard Aedy, ‘Helen McCabe, Australian Women’s Weekly Editor-in-Chief’ Sunday Profile, ABC Local Radio, Interview, 29 September 2013

[9] Melanie Oppenheimer, The Glory Girls: A Study of a Red Cross Relief Unit, and the Volunteer Aids (VAs) Who Served on HMS Glory During the Repatriation Trips, September-December, 1945, M Litt Thesis, University of New England, 1988, p9.

[10] J McQuilton, Seminar, Writing Military History, University of Wollongong, 23 August 1995

[11] Alistair Thomson, Anzac Memories, Living with the Legend, Melbourne: Oxford, 1994, pp5-8, 43-45; Patrick Lindsay, The Spirit of the Digger, Then & Now, Sydney: MacMillan, 2003, pp. 5-20.

[12]. Melanie Oppenheimer, Red Cross VAs, A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales, Walcha: Ohio Productions, 1999, p. xvi.

[13] Julia Bush, Edwardian Ladies and Imperial Power, London, Leicester University Press, 2000, p. 74.

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.