Denbigh open days

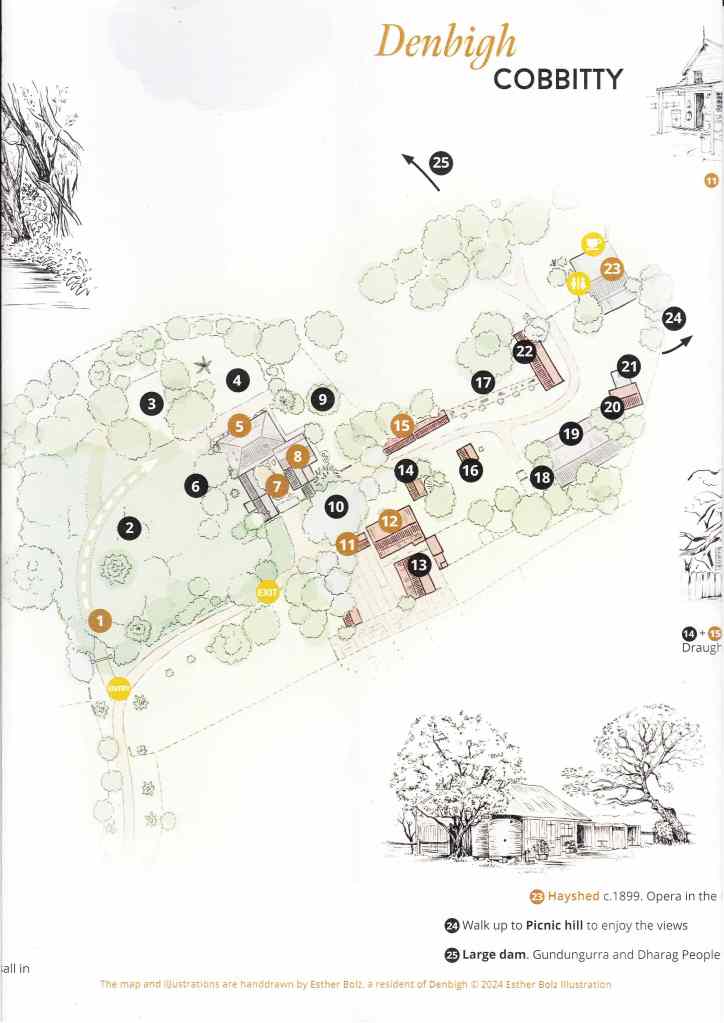

On a recent sunny day in early spring, the McIntosh family unveiled the enchanting gardens of Denbigh for a rare public charity viewing. Visitors were given an informative leaflet on entry with exciting snippets of the site’s history.

The Denbigh open days climaxed the local celebration of History Week 2024, ‘Marking Time,’ when the History Council of NSW invited communities to remember their past.

Denbigh is one of the most important gentry properties of the Cowpastures and one of the oldest English-style colonial farm complexes in Australia. Its current owners have preserved the property’s integrity.

Recalling the past

The picturesque landscape belies violence that once reigned across the district from the property’s foundation in the 1810s.

To the casual observer, this is a picturesque collection of farm buildings in its historic setting surrounded by a bucolic rural landscape.

A more careful examination of this important site reveals much more as part of the settler society project.

The farm buildings reveal the layers of Denbigh’s history, starting with the dispossession of Aboriginal land, then the pastoral stage, followed by dairying, and finally, the urban invasion.

Dark history

The bucolic setting of the Denbigh farm complex belies a dark beginning.

The property, granted to Charles Hook in 1812, was located on the colonial frontier of the Cowpasture on the edge of the British Empire.

As invaders, Hook and other English settlers in the Cowpastures feared confrontation with the Indigenous population and were not disappointed.

Historian Stephen Gapps writes on his Sydney Wars blog that rural domestic architecture in British colonies in the 18th century was ‘almost always defensive element’. According to Louis Nelson, quoted by Gapps, the British colonial presence in foreign lands was marked by ‘a profound and unrelenting anxiety’. (Gapps 2019)

There were fortified houses in Jamaica where there was guerrilla warfare in the countryside, which, according to Nelson, were based on Scottish border ‘tower houses’ or a ‘bastion room’ that would double as a normal room. Many had rifle loopholes that doubled as ventilation holes. (Gapps 2019)

Gapps argues that the 1760 Jamaican rebellion resulted in an ‘intense period of fortified house construction’ based on a ‘fear and anxiety of past events, rather than any actual threat’. He argues that this fear shaped architecture for decades into the 19th century. Gapps surmises that this influenced domestic vernacular architecture in the Sydney Wars in the 1810s. (Gapps 2019)

Denbigh’s founders understood what was happening in other parts of the British Empire, and the general anxiety and fear that permeated locations like Jamaica and the Scottish borderlands found their expression in the Cowpastures.

Hook located his Denbigh farm complex in a defensive position at the top of a shallow valley facing west, surrounded by high ground on the north, east, and south.

One of the first buildings erected was a ‘Fortified Stables and Coachhouse’ around 1812. Now restored as a pottery studio (Denbigh Cobbitty 2024). The building has solid walls and defensive gun slits on the eastern side of the building.

Conflict in the Cowpastures

Denbigh’s founders participated in the Cowpastures guerrilla war in the 1810s and suffered from anxiety and fear from real and anticipated attacks from the local Dharawal and Gundungurra.

The conflict on the Cowpastures colonial frontier was actual enough, with several skirmishes and deaths. Eventually, Governor Macquarie ordered a military expedition in 1816 to quell local unrest, culminating in the Appin Massacre in April 1816.

The 1812 Denbigh Stables and Coachhouse fortification represents that fear and anxiety locally. The eastern wall of the coach house has three rifle slits or gun loops as a defensive arrangement.

Summit homesteads

From the 1820s, peace prevailed across the Cowpastures, and English-style gentry homesteads were located on hilltops and prominent locations. Morris and Britton have called these colonial homesteads the ‘summit models’, where the Cowpastures homesteads were located on hilltops with prominent outlooks and vistas across the countryside. (Morris & Britton 2001)

Among these gentry properties were Camden Park, Harrington Park, Oran Park, Gledswood, Maryland, Kelvin, Bella Vista, Macquarie Fields House, Blair Athol, Brownlow Hill and others.

The location of the Cowpasture gentry estates mirrored the English village church on the hill in the village, with its spire visible from the surrounding countryside. One good example is Camden’s St John’s Church, visible from the Macarthur family’s Camden Park House. The summit homestead replaced the church spire with Bunya Pines and other plantings largely absent at Denbigh. (Morris & Britton 2001)

The prominent tree at Denbigh is a 230 year old red gum located at the front of the Fortified Stables and Coachhouse that pre-dates the farm complex

References

Alan Croker 2006, Denbigh Curtilage Study, Report McIntosh Bros. Design 5 Architects, Sydney.

Stephen Gapps 2019, ‘Rifle slits and gun loops: Early colonial domestic defensive architecture in the Sydney region.’ The Sydney Wars, Conflict in the early colony 1788-1817 Blog, 19 February. Online at https://thesydneywars.com/2019/02/19/rifle-slits-and-gun-loops-early-colonial-domestic-defensive-architecture-in-the-sydney-region/

Morris, Colleen, and Geoffrey Britton 2001. “Curtilages – Getting beyond the Word: Implications for the Colonial Cultural Landscapes of the Cumberland Plain and Camden.” Historic Environment 15, no. 1/2 (2001): 55–63. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.595650008816745.

‘Denbigh Cobbitty’ 2024, Information Leaflet, Denbigh.

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.