The sale of church land creates community angst

The local church is a centre of placemaking in most communities and is especially significant in building community identity and supporting an emotional attachment to place.

St Pauls Anglican Church Bankstown, a ‘sacred place’, under threat

There is trouble brewing for the Sydney Anglican Diocese at Bankstown over the future of the site of St Paul’s Anglican Church.

A fuss has erupted recently around the proposed heritage listing of St Pauls’s Anglican Church at Bankstown that would potentially stop the redevelopment of the church site.

The church parishioners are concerned the site would be converted into a high-rise development.

The church rector claims that a heritage listing will result in the church’s eventual closure due to the maintenance costs.

Local activism led to the Save St Paul’s Bankstown group, which claims that the church is a ‘sacred place‘.

Canterbury Bankstown Council has stated that the church site is part of the Bankstown City Centre Master Plan.

The Anglican Church acquired the site in 1914 and constructed a timber building. A brick church was built in 1938. Architect Norman Wellard McPherson designed the brick church building, and a rectory was added in 1945. McPherson also designed churches at Mosman, Narooma, and Bathurst.

Quandray for church redevelopment

The redevelopment of church property raises ethical dilemmas. Asset-rich churches have tax-exempt status in Australia and profit-making developments, like those at Bankstown, raise serious questions of equity for the community, according to NSW upper house Greens MP Sue Higginson.

Local community buy their local church

Out at Carcoar, the local community stepped up to the mark and purchased their local church, St Paul’s Anglican Church, when it was put up for sale.

Channel Nine’s A Currrent Affair reported in 2019 that

the diocese decided to sell the site [of St Pauls Anglican Church] to pay the bills for the sins of the fathers following the Royal Commission investigation that uncovered crimes by the clergy on young children.

So to save the church, the community raised $450,000 to buy the church.

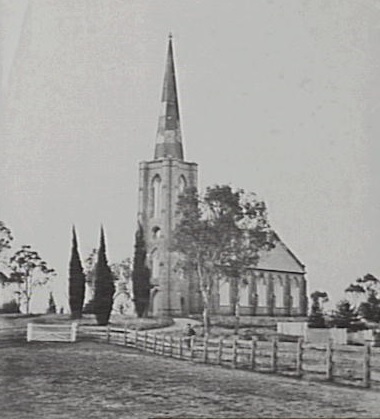

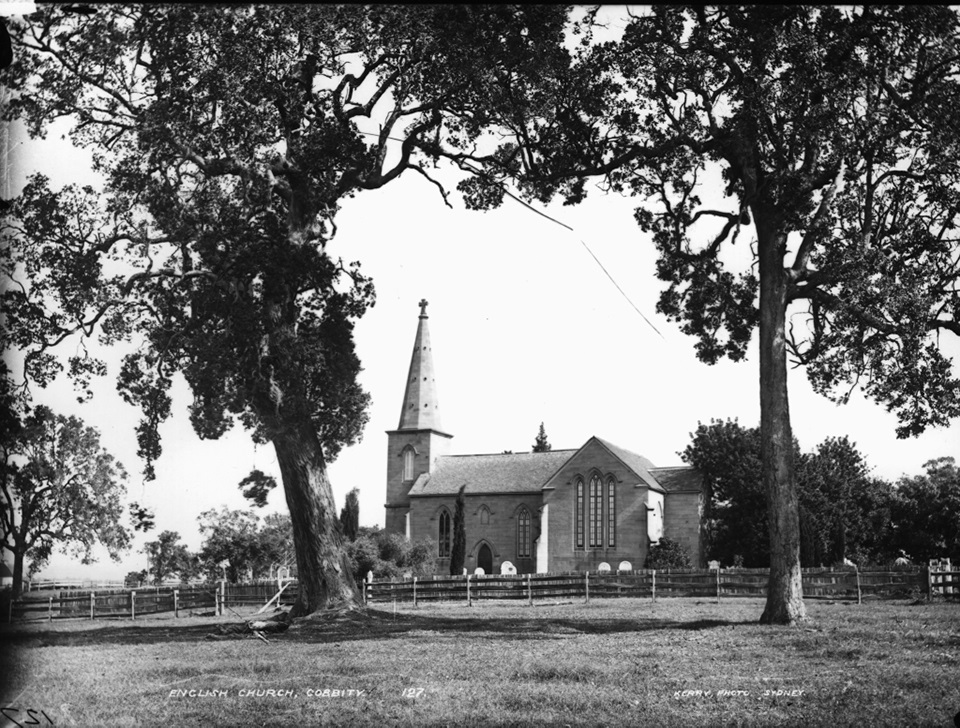

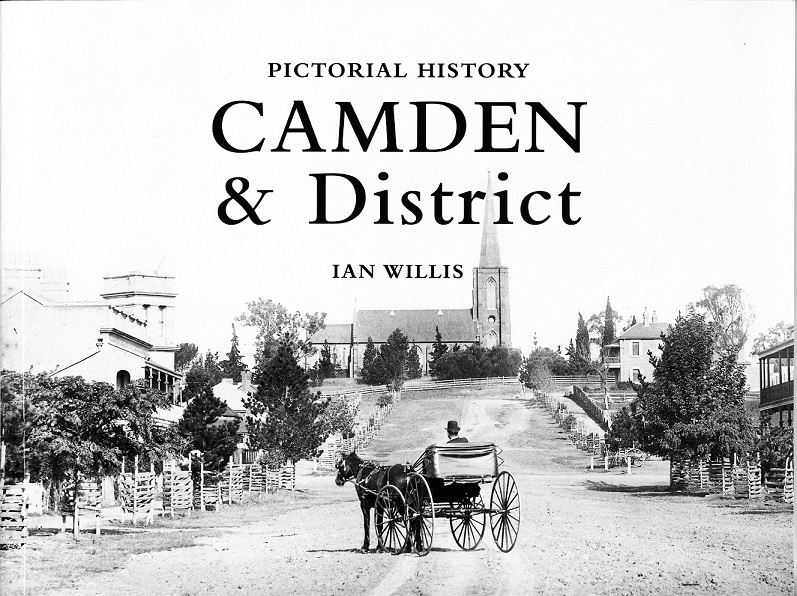

Camden’s St Johns Church

In Camden, non-churchgoers have resisted the sale by the Anglican Church of a horse paddock between St John’s Anglican Church and the former Rectory, all part of the St John’s Church precinct.

Community angst has been expressed at public meetings, protests, placards, and in articles in the press.

Sale of church property

What is going on? Why do non-churchgoers feel so invested in an unused church building or the sale of church property? What is it about the local church to the broader community?

This blog post aims to unravel some of the broader issues underpinning community angst around the sale of church property.

The post will examine the case study of the sale of churches in Tasmania and the resultant community anxiety.

The local church in place

The local church is an integral part of the local community, which has many meanings for both churchgoers and non-churchgoers.

The local church is central to constructing place and people’s attachment to a cultural landscape and locality.

Place is about a sense of belonging and a sense of groundedness. It is expressed by cultural heritage, memory, nostalgia, customs, commemorations, traditions, celebrations, values, beliefs and lifestyles.

Belonging is central to placeness. Home is a site with a sense of acceptance, safety, and security. Home as a place is an important source of stability in a time of chaos. Home is part of a community.

LM Miller from the University of Tasmania states that people are fundamentally involved with what constitutes place, and places are fundamentally involved in constructing persons. Place wraps around and envelopes a person. People are holders of place (Miller: 6-8)

A shared sense of belonging exists in a community where being understood is essential and part of a beloved collection. A sense of belonging is an all-encompassing set of beliefs and identities. It enriches our identity and relationships and leads to acceptance and understanding.

A church is one of these communities.

The local church’s closure, sale and de-consecration threaten a person’s sense of place.

When a person’s sense of place is threatened, their sense of self, identity, safety, stability, and security are challenged.

When a person loses their sense of place and belonging to a place, they go through a grieving process.

Local churches are part of a community’s cultural heritage.

Local churches are part of a community’s cultural heritage.

Cultural heritage consists of two parts. Tangible heritage consists of, for example, buildings, art, objects, and artefacts.

Secondly, intangible cultural heritage includes customs, practices, places, objects, artistic expressions and values. This can include traditional skills and technologies, religious ceremonies, performing arts and storytelling.

Churchgoers and a sense of place

The link between local churches and a community’s sense of place has been explored by Graeme Davison in The Use and Abuse of Australian History. He says that churchgoers are often faced with unsustainable maintenance costs for a church. Eventually, when churchgoers are forced to sell their property they:

‘often seemed less reluctant to give up their church than the rest of the community…and faced with the prospect of its loss, [the non-churchgoers] were often prepared to fight with surprising tenacity to save it.’ (Davision:149)

(Davision:149)

These churches have a strong emotional attachment to their communities. These churches are loved places for their community, and Davison suggests:

It is in losing loved places, as well as loved persons, that we come to recognise the nature and depth of our attachment to our past. (Davison: 150)

(Davison: 150)

Davison argues that churchgoers often are loyal to their local place well beyond their sense of faith in Christianity.

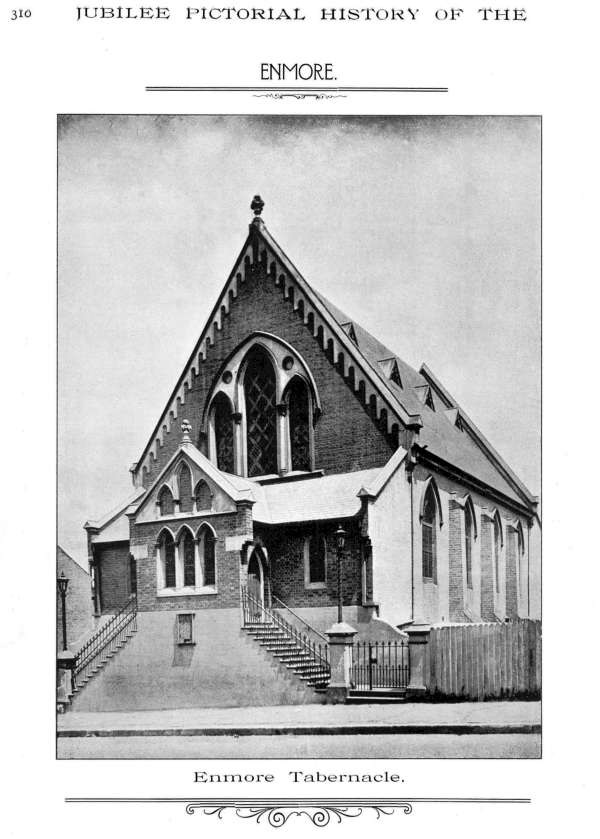

Sale of churches in Tasmania

These issues came to the fore in Tasmania in 2018 when there was public outrage around the sale of local churches in Tasmania.

The Hobart press ran a story titled

‘Emotions run high, communities vow to fight after Anglican Church votes to sell off 76 churches’. (Sunday Tasmanian, 3 June 2018)

(Sunday Tasmanian, 3 June 2018)

The Anglican Church in Tasmania attempted to fund the ‘redress commitment’ to the victims of clerical abuse by selling church property.

In response, Central Tasmanian Highlands churchgoer Ron Sonners said that ‘his ancestors [were] buried in the graveyard associated with St Peter’s Church at Hamilton’…and he ‘struggled with his emotions as he dealt with the fallout from his community church being listed for sale’. (Sunday Tasmanian, 3 June 2018)

(Sunday Tasmanian, 3 June 2018)

Tasmania Anglican Bishop Richard Condie says that most of the opposition to the sale of churches

is primarily people in the broader community who oppose the sales, with the potential loss of heritage and family history, including access to graveyards, their main concern. (The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

(The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

There have been protest meetings, and some affected parishes started fundraising campaigns to keep their churches. The Hobart Mercury reported that

The Parish of Holy Trinity Launceston, which wants to keep St Matthias’ Church at Windermere, has raised the funds, with the help of its local community, to meet its redress contribution. (The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

(The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

A cultural historian and churchgoer, Dr Caroline Miley, said:

the churches are an important part of Australian history… It is unconscionable that such a massive number of buildings, artefacts and precincts should be lost to the National Estate in one fell swoop…These are buildings built and attended by convicts and their jailers. They were built on land donated by early state governors, notable pioneers and state politicians, with funds donated by these colonials and opened by the likes of Sir John Franklin…As well, she says, they contain the honour boards, memorials and graves of those who fought and died in conflicts from the 19th century onwards…Some are in the rare (in Australia) Georgian style or in idiosyncratic Tasmanian Carpenter Gothic. (The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

(The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

Amanda Ducker of the Hobart Mercury summarises the whole fuss surrounding the sale of churches in Tasmania this way:

Condie’s use-it-or-lose-it approach clashes with the keep-it-at-all-costs mentality. But while some opponents of the bishop’s plan refuse to sell their church buildings, neither do they want to go to church regularly. They rather prefer just to gather on special occasions: baptisms, weddings, funerals and perhaps at Christmas and Easter if they are leaning towards piety. But the rest of the year? Well, a sleep-in, potter at home or cafe brunch of eggs benedict (but sans ministering) are pretty tempting on Sunday morning. (The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

The Mercury, 15 September 2018

Other Anglicans in Tasmania see the whole argument differently. Emeritus Professor and Anglican Peter Boyce AO see it as a fight over the spiritual traditions linked to Tasmania’s low and high Anglican traditions. (The Mercury, 15 September 2018)

All these arguments are characteristic of how people, their traditions, their values, their past, and their memories are rooted in a location, particularly a building like a church.

Other dimensions of the argument

The dualism expressed in the sale of church land and buildings can be likened to the difference between sacred and secular. Nick Cave and others explore these two polar opposites in popular culture through music on The Conversation.

Dr David Newheiser aired another perspective on this area on ABC Radio Local Sydney in December 2018. In the discussion, he examined the differences between Christians and atheists. He maintained strong sentiments in the community around tradition and ritual; if you lose a church, you lose all of this.

The binary position of churchgoers and non-churchgoers can also be expressed ethically as the difference between good and evil, right and wrong, moral and immoral, just and unjust and so on. This dichotomy has ancient roots dating back to pre-Biblical times across many cultures.

So what does all this mean?

Churches have an important role in constructing place in communities. Various actors or stakeholders play this role differently.

As far as the dichotomy presented here in the story of the sale of church property and land, no conclusion satisfies all participants.

There is no right or wrong position to the opposing views between churchgoers and non-churchgoers. The differences remain an unresolved ethical dilemma.

An iconic Camden image of St Johns Anglican Church in the 1890s.

References

Graeme Davison 2000, The Use and Abuse of Australian History. Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

LM Miller 2006, ‘Being and Belonging’. PhD Thesis, University of Tasmania.

Update on 29 August 2024. Originally posted on 22 January 2019 as ‘The local church as a centre of place’

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Why does the sale of a local church create community angst? What is going on?”

Comments are closed.