Flooding of the Nepean River could have been at ‘extraordinary’ levels in the past

NSW Reconstruction Authority archaeologists and river experts have been digging holes high on the banks of the Nepean River upstream from Penrith. They have been conducting a “paleoflood” research project, analysing Nepean River flood sediment. (Dalton 2025)

These scientists are attempting to verify or refute Indigenous oral history accounts of the 1780 flood, which was significantly higher than the highest recorded flood in European history -the 1867 flood event.

According to Sydney Morning Herald journalist Angus Dalton, Indigenous oral histories say that the 1780 flood would have spared few areas that were inundated by the 1867 flood, the highest in European records.

Dalton states that, based on current knowledge, the 1780 event had a 1 in 200-year probability, while the 1867 event had a 1 in 500-year probability.

Dr Stephen Yeo, a flood risk specialist at the NSW Reconstruction Authority, says that based on anecdotal evidence, the 1780 flood was approximately three metres higher than the 1867 flood. (Dalton 2025)

According to the NSW Reconstruction Authority, a flood level of 1867 today would necessitate the evacuation of approximately 114,000 people, based on current home development in the area. (Dalton 2025)

Geomorphologist Tim Cohen, an associate professor at the University of Wollongong, standing a hole he dug pointed to a silt layer that represented a 30-metre flood. He stated this represented ‘an extraordinary rain event’ and felt that a flood that high would be ‘nuts’ but theoretically possible. (Dalton 2025)

This fascinating and essential research is outlined in a story written by Angus Dalton in the Sydney Morning Herald. In his reports, he outlines the history of floods, including large past floods and the bathtub effect. (Dalton 2025)

What is the Camden ‘bathtub effect’?

What is the Camden ‘bathtub effect’? Not sure. You’re not alone.

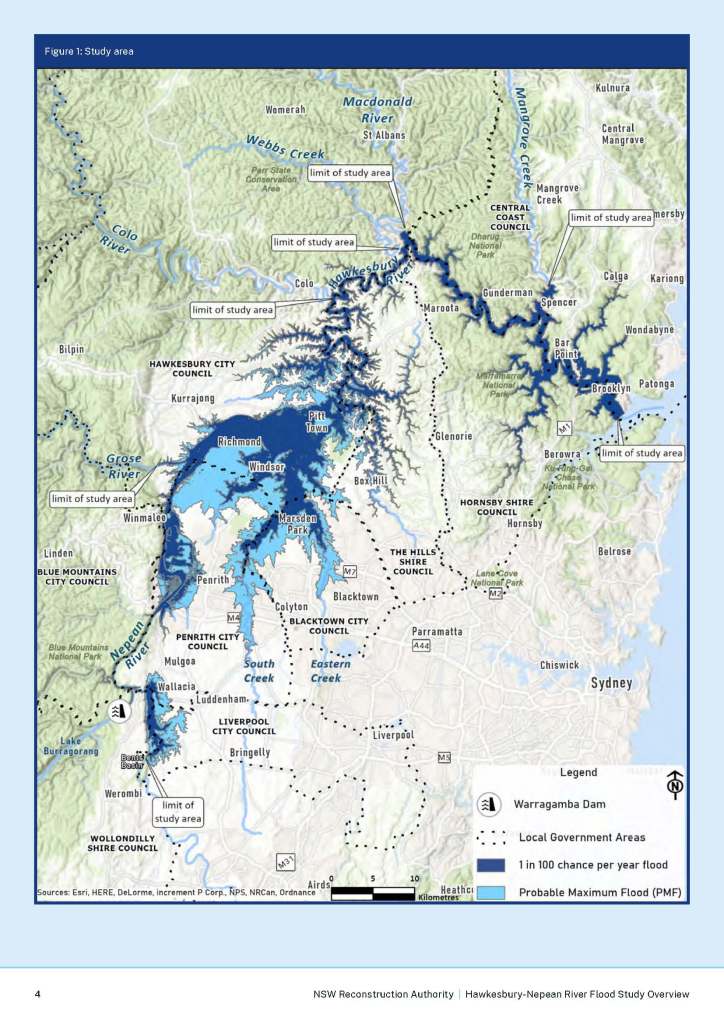

The ‘bathtub effect’ is part of the flooding effect created by the landform that makes up the Hawkesbury-Nepean River system. The river has a unique floodplain system that creates particular problems for local residents and others along the river.

The Hawkesbury-Nepean River valley has several pinch points that constrict the flow and create localised flooding upstream. This has been termed the ‘bath-tub effect’ by engineering geologist Tom Hubble from the University of Sydney in 2021. (Hubble 2021)

The bathtub effect is explained in a NSW SES document, which states

The unique geography in the valley affects the extent and depth of flooding in the region. Most river valleys tend to widen as they approach the sea. The opposite is the case in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley, which means floodwaters flow into the valley more quickly than they can flow out, causing them to back up and rise rapidly. Much like a bathtub with five taps (the major tributaries) turned on, but only one plug hole to let the water out. (NSWSES 2024)

The NSW Department of Primary Industry noted in 2014:

The natural characteristics of the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley make it particularly susceptible to significant flood risk. The combination of the large upstream catchments and narrow downstream sandstone gorges results in floodwaters backing up behind these natural ‘choke points’

http://www.infrastructure.nsw.gov.au/media/1798/hawkesbury-nepean-valley-flood-management-summary-report.pdf

The Hawkesbury-Nepean River system has four localised floodplains created by four choke points along the river. Each of these ‘choke points’ is created by a local gorge along with the river system – Bents Basin Gorge, Nepean Gorge, Castlereagh Gorge and the Sackville Gorge.

Each of the four localised floodplains upstream from the four gorges acts like a ‘bathtub’ in a period of high rainfall, with floodwater flow choked off by the gorges. The gorge restricts the flow of floodwater, and the river rises quickly behind the gorge at the end of the local floodplain.

Camden’s ‘bathtub effect’

The 2015 Nepean River Flood Plain Report and the flood maps clearly show how the Bents Basin Gorge acts as a ‘choke point’. The gorge creates a ‘bathtub’ upstream along with the Nepean River floodplain from the entrance of the gorge. The floodplain upstream from the gorge starts around Rossmore and continues upstream to Cobbitty, Camden, and Menangle.

While the Camden ‘bathtub effect’ is not as dramatic and dangerous as those created in the Penrith-Emu Plains area or the effect of the Sackville Gorge at Windsor and Richmond, it is real.

The 2015 study says (pp1-2) that while floods are ‘rare’, they happen:

flows escaping from the Nepean River are known to inundate the low lying areas of Camden and certain sections within South Camden and Elderslie. Floodplain areas along many of the tributaries of the river (particularly Narellan Creek and Matahil Creek) are also known to be affected by backwater flooding from the Nepean River during flood events.

https://www.camden.nsw.gov.au/assets/pdfs/Environment/Flood-Information/Nepean-River/Nepean-River-Flood-Study-April-2015-Report-Body-1.3MB.pdf

Characteristics of local flooding

The 2016 Camden Local Flood Plan says:

Floods are characterized by rapid river rises with flooding commencing as quickly as 6-12 hrs after the commencement of heavy rain if the catchment is already saturated. Under flood conditions, the Nepean River overflows its banks and commences to inundate the low lying floodplain around Camden during floods of 8.5m on the Cowpasture Bridge gauge. (Appendix, pp. A1-A3)

https://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/media/1600/plan-camden-lfp-mar-2016-endorsed.pdf

Causes of flooding along the Hawkesbury-Nepean River on the Camden floodplain

The Upper Nepean Catchment is the headwaters of the Nepean River floodplain at Camden. This geographic area is drained by the Avon, Cataract, Cordeaux, and Nepean Rivers, with dams located on each of these waterways.

The catchment of the Nepean River above the Warragamba River junction, below Warragamba Dam, is around 1800km2

The wettest conditions are usually created by low-pressure systems, known as east coast lows, that form off the South Coast of New South Wales. The low-pressure systems moving onshore, combined with the Illawarra Escarpment’s orographic effect, can produce heavy rainfall events. (AdaptNSW 2025)

The 2016 Camden Local Flood Plan says:

Many localities in the catchment have received in excess of 175mm in a 24 hr period. (Appendix, pp. A1-A3)

https://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/media/1600/plan-camden-lfp-mar-2016-endorsed.pdf

The most significant local floods on the Camden floodplain

The 2016 Camden Local Flood Plan states:

Floods have occurred in all months of the year. The highest recorded flood at Camden occurred in 1873, when a height of 16.5m was recorded on the Camden gauge (approximately a 200yr ARI). [Cowpasture Bridge, Camden]

Other major floods occurred in 1860 (14.1m), 1867 (14.0m), and 1898 (15.2m). In recent times, major floods have occurred in 1964 (14.1m) and 1978 (13.5m) with moderate to major flooding occurring in 1975 (12.8m) and 1988 (12.8m). (Appendix, pp. A1-A3)

https://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/media/1600/plan-camden-lfp-mar-2016-endorsed.pdf

![Camden Airfield 1943 Flood Macquarie Grove168 [2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/camden-airfield-1943-flood-macquarie-grove168-2-e1507949232355.jpg)

A report of the 1898 flood event at Camden, taken from the Camden News 17 February 1898 gives clarity of how quickly the river can rise in the local area:

Near midnight on Saturday rain began to fall, at first with moderation, towards day break gusts of wind sprang up from the South East bringing heavy rain, lowering the crops in its passage, even majestic trees were torn up by their roots and in sheltered paddocks the trees were denuded of large limbs.

Sunday all day the wind blew with hurricane force; early on Monday morning the storm somewhat abated in its velocity.

Even on Sunday midnight no apprehension of a flood was anticipated by the Camden townspeople the continuous rain and boisterous weather, however made the more Cautious anxious, and one tradesman took the precaution to look after his horses in near paddock when the danger of a flood was manifested to him, the Nepean River had suddenly risen and was flooding the flats.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133282279

Camden News 17 February 1898

A report in the Camden News of the 1911 Camden flood event provides further clarity around the behaviour of the river:

The rain of Thursday, it may naturally be expected filled creeks, dams and watercourses to overflowing, but the climax came with a heavy storm between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m., when some four inches [100mm] of rain fell. This brought the local water down from the adjoining hills in torrents, the Main Southern Road and Carrington Road were then covered with some two feet of fast rushing water, and on Druitt Road the local flood was then absolutely impassable..

In the early hours the Nepean River rose rapidly, and before the arrival of the first train the bridge was impassable ; the water continued to rise till about 3.15 in the afternoon, it having then reached it highest point, covering the new embankment between the town and the bridge, running through the Chinese quarters on the one side, and just into the pavilion on the show ground on the other. From near Druitt Road to Beard’s Lane was one long stretch of water….

Sackville Gorge and the Windsor & Richmond ‘bathtub effect’

In 2012, Steve Opper, the director of community safety with the State Emergency Service, argued that the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley has a unique shape that can lead to catastrophic flooding.

He describes the effect of the Sackville Gorge on the Hawkesbury-Nepean River:

“The Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley is throttled down by a narrow gorge down near what’s called Sackville, which is just upstream of Wiseman’s Ferry,” he said.

“The result of that is that the water can flow into the top of the system very, very rapidly, can’t get out, and so you get very dramatic rises in the level of the river.

“So normal river level might be two metres; if you’re at the town of Windsor and in the most extreme thought possible, that could rise up to 26 metres, which is a number that’s quite hard to comprehend.”

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-02-15/planning-shows-catastrophic-flood-would-sink-sydney-suburbs/3832496%202/3

John Thomas Smith reported in the Sydney Morning Herald, 2 July 1867 after a flood event that

‘The enormous body of water rushing down with relentless force on its way to the sea could not be easily described, nor its effects conceived. About the neighbourhood of Windsor, now that the waters are fast subsiding, the scene is most dreary, and the destruction caused be -comes every day more apparent. The feeling of bitter anguish expressed not in words but in the blank look of utter despair would move the most hardened.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13149663

Conclusion

Flooding is a regular part of the cycle of the Hawkesbury-Nepean River system, as it is for any river basin in Australia. The Hawkesbury-Nepean River basin is one of the highest flood risk zones in Australia.

The particular landform features of the Hawkesbury-Nepean, with the four gorges along the river, produce four localised floodplains. Each localised floodplain creates a local ‘bathtub effect’ in each location.

The landform of the four river gorges creates severe flooding for local communities along the river system. Severe rain events have occurred in the past and are likely to happen again in the future.

High flood levels on the Hawkesbury-Nepean River basin should be noted by both residents and the government. The evacuation of large numbers of people during a flood event presents a significant logistical challenge for emergency services.

Approval of new land releases in known flood-prone areas does nothing to help the situation and only exacerbates it in the future.

Resources

AdaptNSW 2025, Climate Change Impacts on storms and floods. NSW Government. Online at https://www.climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/impacts-climate-change/weather-and-oceans/storms-and-floods Viewed 27 July 2025.

Hubble, T. (2021). Sydney’s disastrous flood wasn’t unprecedented: we’re about to enter a 50-year period of frequent, major floods. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/sydneys-disastrous-flood-wasnt-unprecedented-were-about-to-enter-a-50-year-period-of-frequent-major-floods-158427

Dalton, A. (2025). A megaflood devastated early Sydney. An even worse catastrophe is hidden in the city’s ‘bathtub’. [online] The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/a-megaflood-devastated-early-sydney-an-even-worse-catastrophe-is-hidden-in-the-city-s-bathtub-20250721-p5mggu.html [Accessed 26 Jul. 2025].

NSW SES 2024, Understand more about floods in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley. State of New South Wales (NSW State Emergency Service), Sydney. Online at https://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/plan-and-prepare/hawkesbury-nepean-valley-area/understand-more-about-floods-in-the-hawkesbury-nepean-valley (Viewed 26 July 2025)

NSW RA 2024, Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley Flood Risk Management. NSW Government (NSW Reconstruction Authority), Sydney. Online at https://www.nsw.gov.au/departments-and-agencies/nsw-reconstruction-authority/our-work/hawkesbury-nepean-valley-flood-risk-management Viewed 26 July 2025.

Updated 26 July 2025. First posted on 29 November 2019 titled Floods and the Camden ‘bathtub effect’

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

5 thoughts on “The hidden dangers of Camden’s bathtub effect”

Comments are closed.