Camden Museum sewing machine

The Camden Museum has a number of sewing machines, and one treadle model is just inside the front door. What is the importance of the museum’s sewing machine?

Virtually all women in Camden sewed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was part of their domestic duties. Hand sewing was tedious and labour-intensive, requiring extended hours to make shirts, dresses, and other items.

Many women in Camden owned sewing machines, and some even operated their own businesses as dressmakers. The sewing machine exemplified industrial modernism in an Australian country town, illustrating how it transformed women’s agency in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Sewing has a long history

Sewing has a long history going back thousands of years. Australian Indigenous women were skilled sewers and made possum-skin cloaks using crude wooden sewing needles.

The women on the First Fleet brought sewing skills with them to make and repair their own clothing. From colonial times, women were expected to sew as part of their family and womanly duties.

A great gift to women

In the 19th century, one woman proclaimed that the sewing machine, alongside the Bible, was the greatest gift women had, enabling them to devote more time to themselves and their children. (McCaffrey, H. (2025).

McCaffrey argues that the sewing machine democratised work and was a gift to women because it gave them time to care for their children and undertake other activities (McCaffrey, H. (2025).

Introduction of the sewing machine

The introduction of the sewing machine in the late 19th century had a profound impact on both sewing and fashion.

By the mid-19th century, a flurry of inventions, innovations and patents led to the creation of the treadle sewing machine. The Singer company manufactured its first sewing machine for domestic use in 1856, which could also be converted into a wooden table with a cabinet.

In the USA, Singer introduced time payment for purchasing sewing machines.

The sewing machine made its way into domestic spaces, becoming an addition to the household furniture, alongside the piano. The sewing machine conferred status on a middle-class household. (McCaffrey, H. (2025).

Anxiety for female morality

The entry of a machine into the private domestic space of the home created anxieties among some men, as the home was seen as a moral feminine refuge from the public world of men in an industrialising world and its perceived immorality. (McCaffrey, H. (2025).

In the Sydney press, a syndicated London Times report on the sewing machine reported that, ‘At the present moment, with the exception of one trade, the sewing-machine may be said to be wholly in the hands of the women’. (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1864)

The story stated the sewing machine had improved the wages and status of ‘needlewomen everywhere’, maintaining that machine operators could make 5s a week. For a needlewoman working 16 hours a day, this would have been a good wage. The reporter maintained that they visited a London shirt-maker the ‘young girls’ were earning wages of between 12s and 20s a week, and the girls looked ‘healthy, merry and bright’. (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1864)

The story maintained that in the United States, the sewing machine had become a ‘domestic institution’ and young girls received training on the sewing machine at school. (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1864)

Hysterical and nervous diseases

In 1870, a syndicated story from the Pall Mall Gazette appeared in the NSW country press. It maintained that the sewing machine was causing ‘various hysterical and nervous diseases among the persons who were in the habit of making continual use of it’. (Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser, Saturday 6 August 1870, p 4)

The Hamilton Spectator (Victoria) warned in 1873 of the health risks associated with the use of the sewing machine. The report maintained that the State Board of Health of Massachusetts maintained that ‘uterine and ovarium maladies’ were made worse by even the occasional use of the sewing machine. The report did acknowledge that the sewing machine had brought many benefits, including increased wages for seamstresses, shortened the domestic hours of sewing at home, and noted that most women of moderate health would escape injury. (Hamilton Spectator, Saturday 29 November 1873, 1 (2))

Time-saving capacities

In 1862, the Sydney press carried a story from the New York Tribune extolling the sewing machine’s time-saving capabilities. It maintained that a sewing machine was a ‘family necessity, one that no family could afford to do without’ and carried out comparisons between machine sewing times and hand-sewing. A man’s shirt that took over 14 hours to make by hand was machine-sewn in a little over one hour, while a silk skirt hand-sewn in 8½ hours could be machine-sewn in little over one hour, and a silk apron machine-sewn in 15 minutes took over four hours to hand-sew. (Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 8 September 1862, page 5 (3) )

In conclusion, the New York Tribune report stated

‘Instead of injuring the trade of the seamstress it has proved to her tx blessing. It has created work for her. It is used in such a variety of ways, and so cheapened clothing that it has created demand, and given more employment to sewing women.’ (Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 8 September 1862, page 5 (3) )

Strength and stamina

A letter writer to the editor of the Melbourne Age in 1873 was concerned that women who used sewing machines. Women needed a ‘first-rate constitution and a considerable amount of strength and stamina’. The writer maintained that girls needed to be at least 18 before using a sewing machine so that they could fulfil their duty to their husband, their family, and society. (Age (Melbourne), Saturday 24 May 1873, p 7)

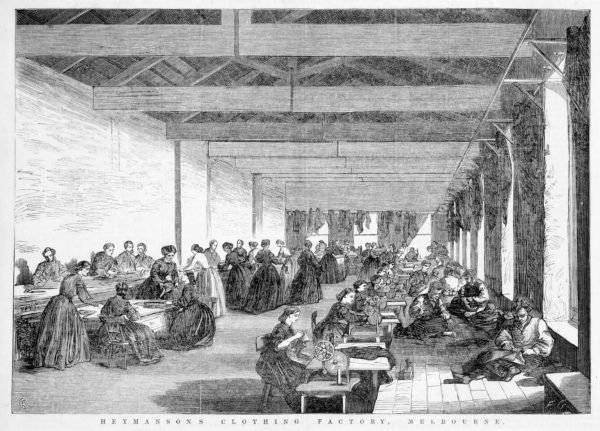

Sweatshop conditions in Ballarat

There was a report in the Melbourne Argus about the sweat-shop conditions in sewing factories in Ballarat. The young girls, aged 13-15, were working in factories with 200 to 300 sewing machines, often working excessively long hours, with some working from 9 am to 7 pm or later. The girls complained of being dizzy and having headaches. (Argus (Melbourne), Monday 12 May 1873, p 6)

Oswald Rose Campbell, artist, Frederick Grosse, engraver

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Paper patterns

McCaffrey maintains that paper patterns revolutionised the ‘women’s sewing work’ .

The tissue-paper patterns were affordable, came in a variety of sizes, included instructions, were fashionable, and in the words of scholar Margaret Walsh, democratized the women’s clothing industry. McCaffrey, H. (2025).

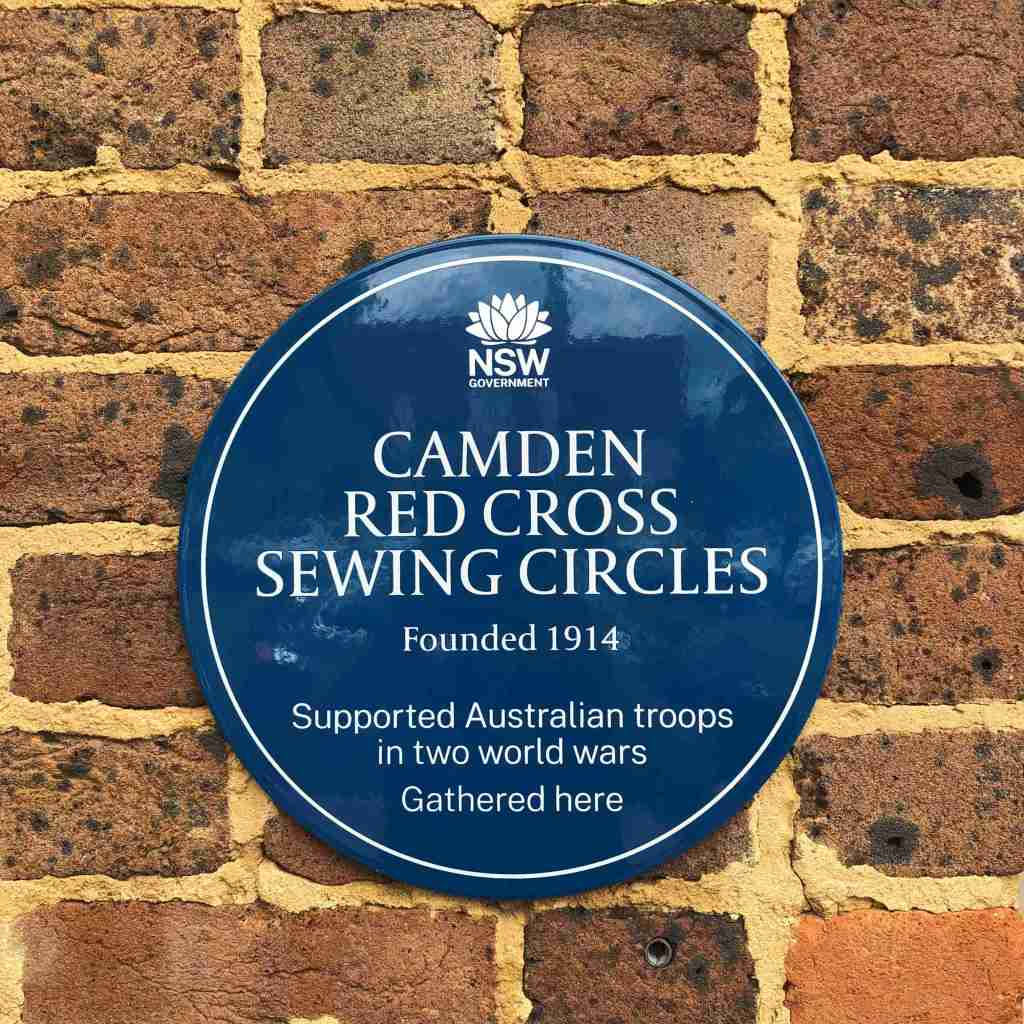

Red Cross sewing circles

Women in Camden’s Red Cross sewing circles used sewing machines for patriotic purposes during the First and Second World Wars. (Willis 2023)

The Camden Red Cross sewing circles were one of Camden’s most important voluntary patriotic activities during World War I and World War II. The sewing circles began at the Camden School of Arts in 1914, and due to a lack of space, they moved to Foresters’ Hall in Argyle Street in 1918. At the outbreak of the Second World War, sewing circles reconvened in 1940 at the Camden Town Hall in John Street (the old School of Arts building – the same site as the First World War)

These sewing circles were workshops where women from Camden volunteered and manufactured supplies for Australian military hospitals, field hospitals, and casualty clearing stations. They were held weekly on Tuesdays, which was sale day in the Camden district. (Willis 2014, 2023)

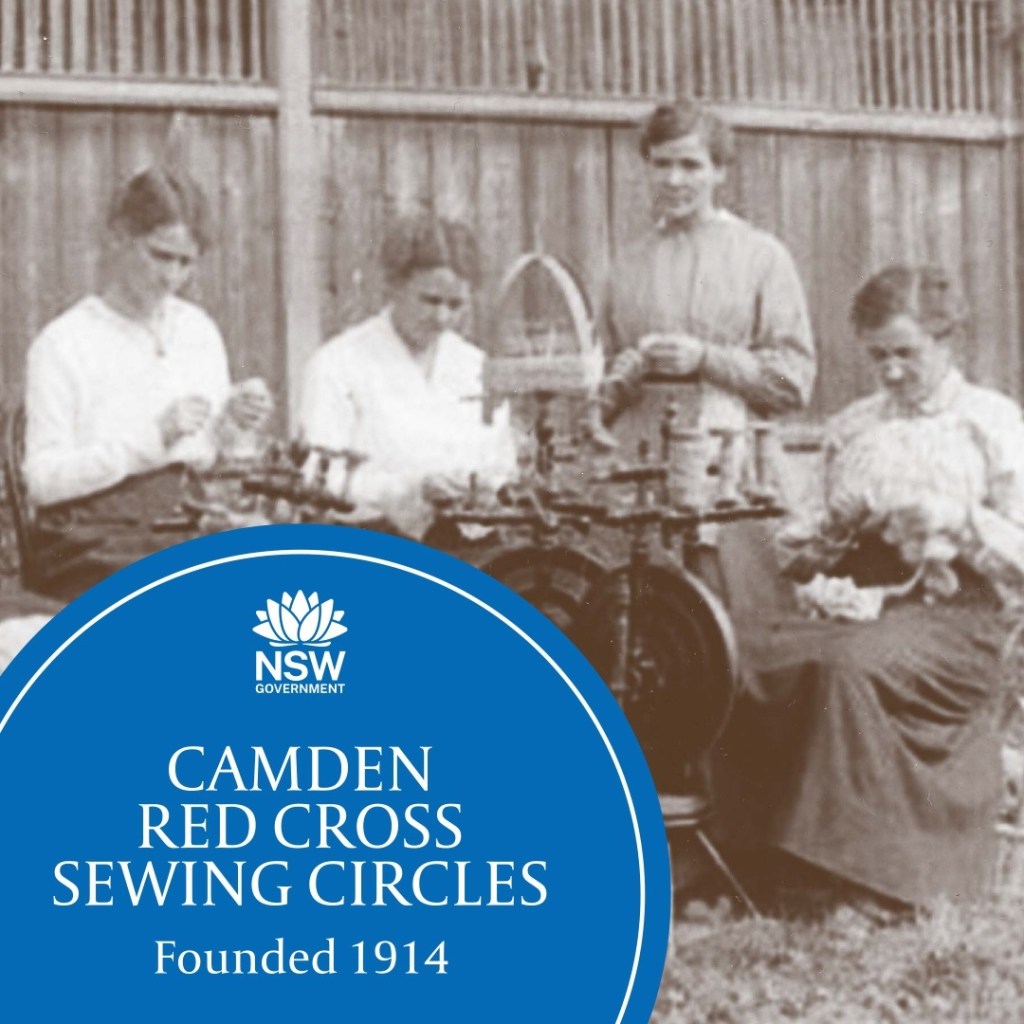

Quasi-industrial production lines

Sewing circles were ‘quasi-industrial production lines’ where Camden women implemented their domestic skills to aid the war at home and were lent several sewing machines in both wars.. Camden women cut out, assembled, and sewed together hospital supplies, including flannel shirts, bed shirts, pyjamas, slippers, underpants, feather pillows, bed linen, handkerchiefs, and kit bags.

During the First World War, the sewing circles attracted between 80 and 100 women each week. The list of hospital supplies was strikingly consistent across both wars, with the only significant addition during the Second World War being knitted pullovers and cardigans. The sewing circles also coordinated knitting and spinning for bed socks, stump socks, mufflers, balaclava caps, mittens, cholera belts (body binders) and other items. The women also made ‘hussifs’ or sewing kits for the soldiers. (Willis 2014, 2023)

Prodigous patriotism

The Camden women’s production output was prodigious. Between 1914 and 1918, women from the Camden Red Cross sewing circle created over 20,300 articles, totalling more than 40,000 volunteer hours. Between 1940 and 1946, during World War II, women contributed over 25,000 articles, totalling more than 45,000 voluntary hours.

The operation of the sewing circles was fully funded by the Camden Red Cross and community donations. In 1917 alone, over 95% of branch fundraising was dedicated to these activities. (Willis 2014, 2023)

Little recognition in many locations

In World War One, other Red Cross sewing circles in the Camden district were located at The Oaks, Camden Park, Theresa Park, and Middle Burragorang. During World War Two, other centres across the local area included Bringelly-Rossmore, Menangle, Narellan, and The Oaks. Each group independently funded its activities.

These patriotic voluntary activities by Camden women were part of the war at home and have received little recognition at a local, state or national level. Wartime sewing and knitting have been kept in the shadows for too long. There needs to be a public acknowledgement of these women’s patriotic efforts. (Willis 2014, 2023)

Conclusion

The Camden Museum sewing machine has a complex, multi-layered history with transnational connections spanning the globe. The sewing machine exemplified the transfer of industrial technology worldwide and its infiltration into women’s private domestic space.

McCaffrey argues

by the turn of the 20th century, sewing machines—once indicative of middle-class domesticity—quickly became a basic necessity in every home as more and more working-class women found the means to purchase the machines, whose prices were rapidly dropping. (McCaffrey, H. (2025)

Camden women had sewing machines in their homes from the late 19th century, and some used these machines to run their own dressmaking businesses. These businesses enabled women to showcase their skills and assert their agency in a small, rural community.

Local women, like those around the world, were able to save time making clothing for their families and spend more time with their children and doing things they wanted to do for themselves.

The sewing machine enhanced women’s agency, confidence, and independence, enabling them to utilise their time more productively and effectively for themselves, their families, and the community.

Camden Red Cross women used sewing machines for patriotic purposes during the First and Second World Wars, spending thousands of hours assisting the war effort on the home front. (Willis 2023)

These activities have been memorialised by an NSW Blue Plaque on the front of the Camden Museum Library building, formerly the Camden Town Hall, in John Street, and is the only recognition for this effort in Australia. There were hundreds of sewing circles across the country, and they have mostly been completely forgotten and fallen into the shadows of history.

Resources

Daniel (2025). The Rich and Threaded History of Sewing. [online] Superprof.com. Available at: https://www.superprof.com.au/blog/history-of-sewing/ [Accessed 25 Sep. 2025].

McCaffrey, H. (2025). A Sewing Revolution | The New York Historical. [online] Nyhistory.org. Available at: https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/a-sewing-revolution [Accessed 25 Sep. 2025].

Walsh, Margaret, 1979, The Democratisation of Fashion: The Emergence of the Women’s Dress Pattern Industry, Journal of American History, Volume 66, Issue 2, September, Pages 299–313, https://doi.org/10.2307/1900878

Willis, Ian. 2014. Ministering Angels: The Camden District Red Cross, 1914-1945. Camden Historical Society, Camden.

Willis, I. (2023). The Camden Red Cross sewing circles | Blue Plaques | Environment and Heritage. [online] Environment and Heritage. Available at: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/heritage/blue-plaques/camden-wartime-sewing-circles [Accessed 5 Jan. 2026].

Updated on 5 January 2026. Originally posted on 27 September 2025.

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.