A colonial region

It is hard to imagine now, but in days gone by, the township of Camden was the centre of a large district. For over a century, the Camden district became the centre of people’s daily lives and the basis of their sense of place and community identity.

The Camden district was created by linking peoples’ social, economic, and cultural lives across the area. All are joined together by a shared cultural identity and cultural heritage based on common traditions, commemorations, celebrations and rituals. These were reinforced by personal contact and family kinship networks. The geographers would call this a functional region.

![Map Camden District 1939[2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/map-camden-district-19392.jpg)

The Camden district ran from the Main Southern Railway around the estate village of Menangle into the gorges of the Burragorang Valley in the west. The southern boundary was the Razorback Ridge, and in the north, it faded out at Bringelly and Leppington.

The district grew to about 1200 square kilometres with a population of more than 5000 by the 1930s through farming and mining. Farming started with cereal cropping and sheep, which turned to dairying and mixed farming by the end of the 19th century. Silver mining started in the late 1890s in the Burragorang Valley, and coal mining from the 1930s.

The district was centred on Camden, and there were several villages, including Cobbitty, Narellan, The Oaks, Oakdale, Yerranderie, Mt Hunter, Orangeville and Bringelly. The region comprised four local government areas – Camden Municipal Council, Wollondilly Shire Council, the southern end of Nepean Shire and the south-western edge of Campbelltown Municipality.

Cows and more

Before the Camden district was even an idea, the area was the home of ancient Aboriginal culture based on Dreamtime stories. The land of the Dharawal, Gundangara and the Dharug.

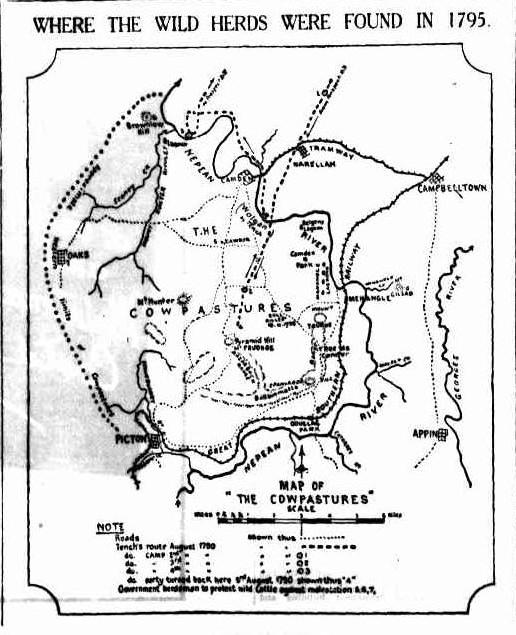

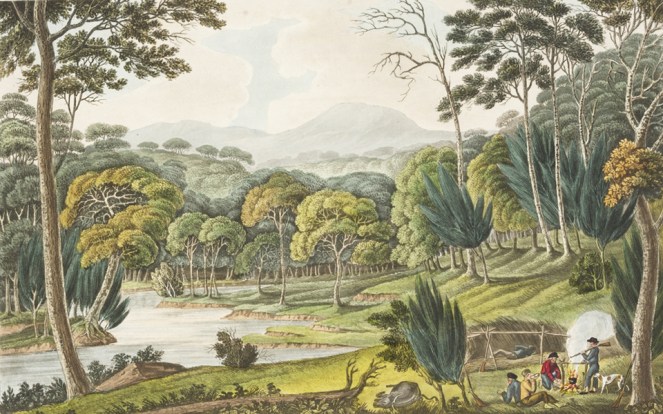

The Europeans arrived in their sailing ships, bringing new technologies, ideas, and ways of doing things. The First Fleet cows did not think much of their new home in Sydney. They escaped and found heaven on the Indigenous-managed pastures of the Nepean River floodplain.

On discovering the cows, an inquisitive Governor Hunter visited the area and called it the Cow Pasture Plains. The Europeans seized the territory, allocated land grants, and displaced the Indigenous occupants. They created new land in their own vision of the world: a countryside comprised of large pseudo-English-style estates, an English-style common called The Cowpasture Reserve, and English government men to work it called convicts. The foundations of the Camden district were set.

A river

The Nepean River was at the centre of the Cowpastures and the gatekeeper for wild cattle. Its Aboriginal name is Yandha. Governor Arthur Phillip named it in 1789 in honour of Evan Nepean, a British politician.

The Nepean River rises in the ancient sandstone country west of the Illawarra Escarpment and Mittagong Range around Robertson. The shallow V-shaped valleys were ideal locations for the Upper Nepean Scheme dams built on the tributaries to the Nepean, the Cordeaux, Avon, and Cataract.

The river’s catchment drains northerly and cuts through deep gorges in the Douglas Park area. It then emerges out of the sandstone country and onto the floodplain around the village of Menangle. The river continues in a northerly direction downstream to Camden, then Cobbitty, before re-entering the sandstone gorge country around Bents Basin, west of Bringelly.

The river floodplain and the surrounding hills provided ideal conditions for the woodland of ironbarks, grey box, wattles and a ground cover of native grasses and herbs. The woodland ecology loved the clays of Wianamatta shales, which are generally away from the floodplain.

The river’s ever-changing mood has shaped the local landscape. People forget that the river could be an angry, raging, flooded torrent on a destructive course. Flooding shaped the settlement pattern in the eastern part of the district.

![Camden Airfield 1943 Flood Macquarie Grove168 [2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/camden-airfield-1943-flood-macquarie-grove168-2-e1507949232355.jpg)

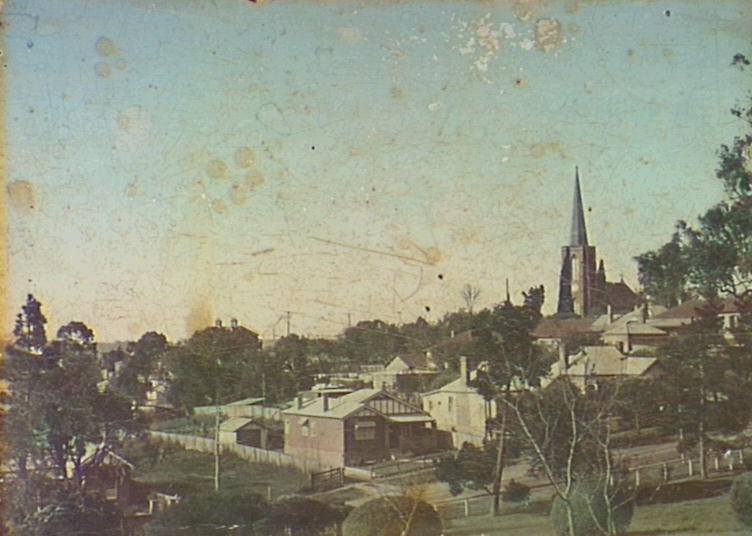

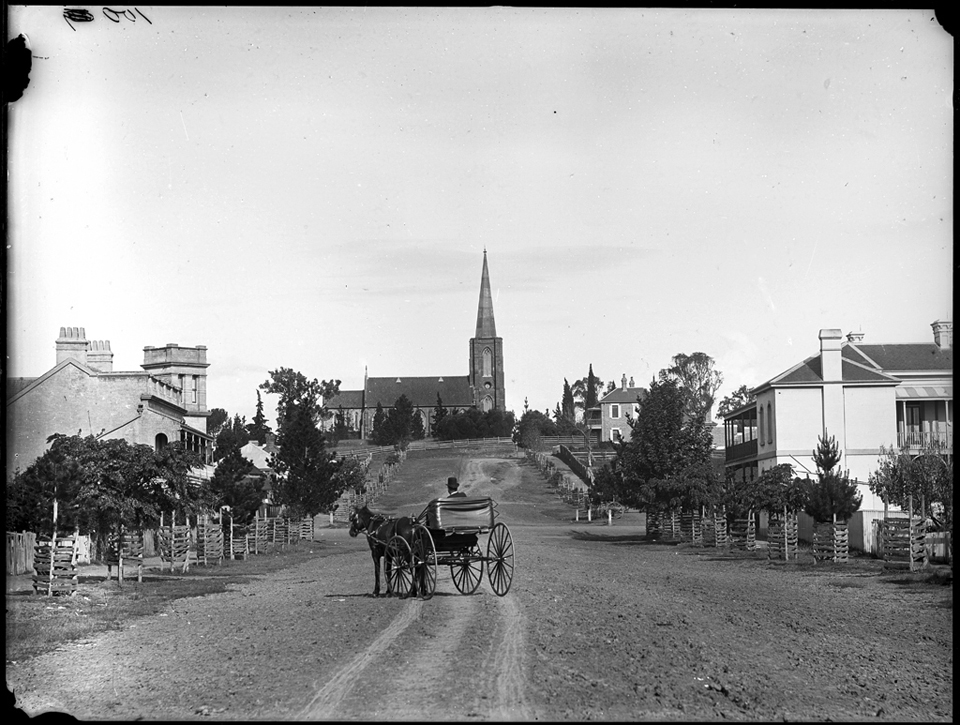

A village is born

The river ford at the Nepean River crossing provided the location of the new village of Camden established by the Macarthur brothers, James and William. They planned the settlement on their estate of Camden Park in the 1830s and sold the first township lots in 1840. The village became the district’s transport node and developed into the area’s leading commercial and financial centre.

Rural activity was concentrated in the new village of Camden. There were weekly livestock auctions, the annual agricultural show and the provision of a wide range of services. The town was the centre of law enforcement, health, education, communications and other services.

The voluntary community sector started under the direction of mentor James Macarthur. His family also determined the moral tone of the village by sponsoring local churches and endowing the villagers with parkland.

Manufacturing was present, with a milk factory, a timber mill, and a tweed mill on Edward Street that burned down. Bakers and general merchants had customers as far away as the Burragorang Valley, Picton, and Leppington, and the town was the publishing centre for weekly newspapers.

The Hume Highway, formerly the Great South Road, ran through the town from the 1920s and brought the outside forces of modernism, consumerism, motoring, movies, and new-fangled flying machines to the airfield. This reinforced the market town’s centrality as the district’s commercial capital.

Burragorang Valley

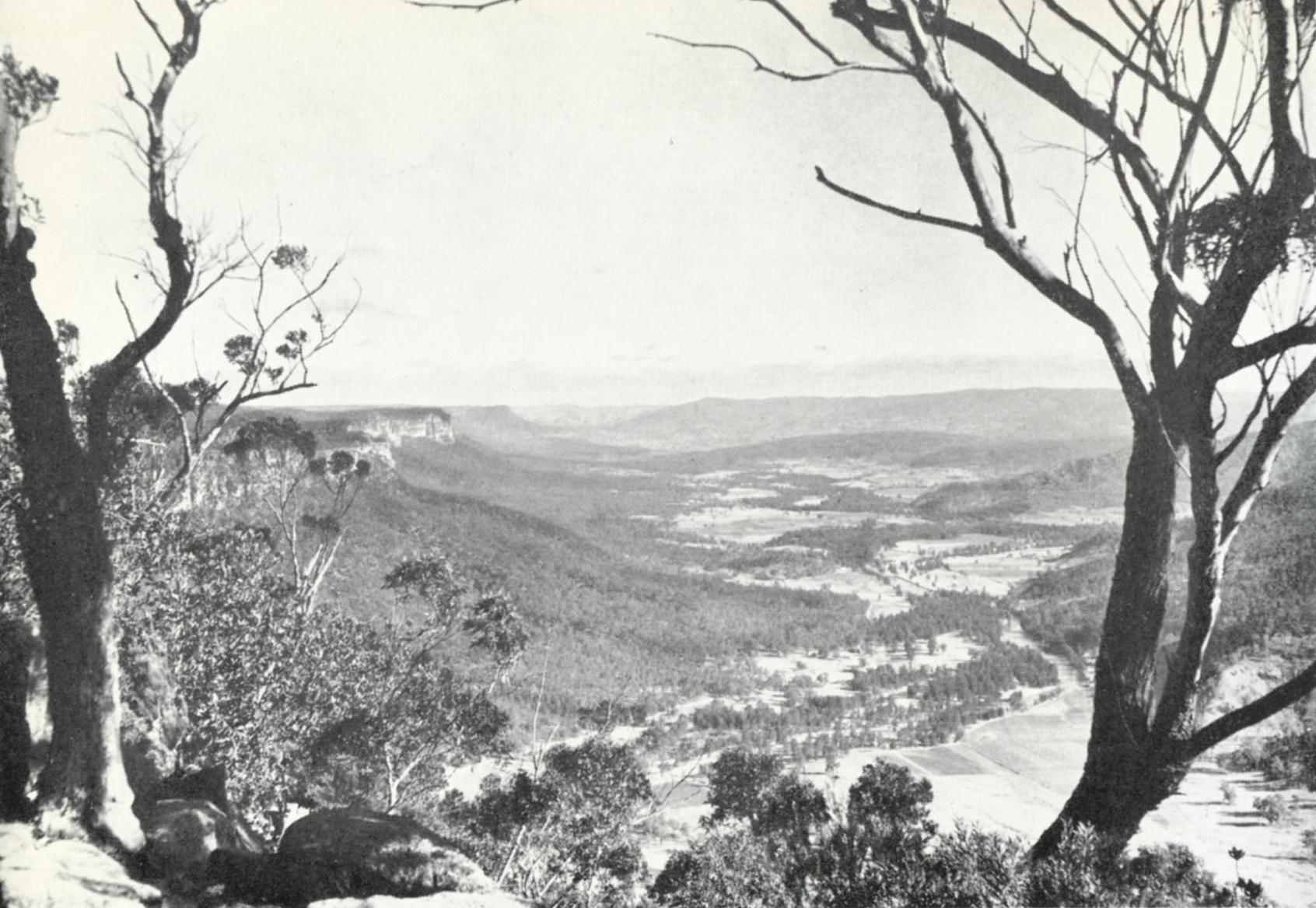

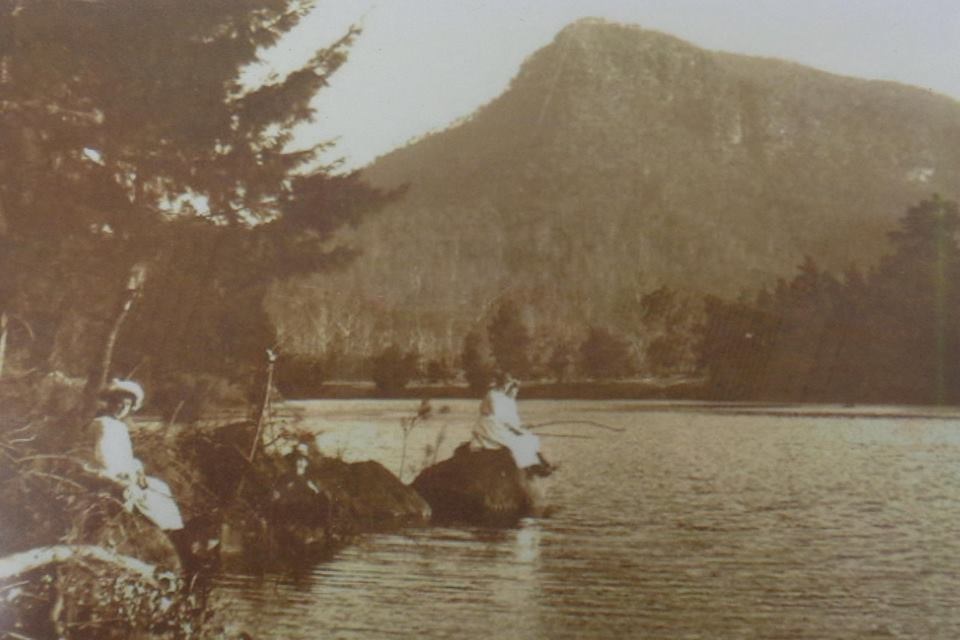

In the district’s western extremities, the rugged mountains formed the picturesque Burragorang Valley. Its deep gorges carried the Coxes, Wollondilly, and Warragamba Rivers.

Access was always difficult from the time the Europeans discovered its majestic beauty. The Jump Up at Nattai was infamous when Macquarie visited in 1815.

The valley became an economic driver of the district, supplying silver and coal hidden in the dark recesses of the gorges. The Gothic landscape attracted tourists who stayed in one of the many guesthouses to soak up the valley’s hypnotic beauty.

The outside world was linked to the valley through the Camden railhead and the daily Camden mail coach, which operated from the 1890s and was later replaced by a mail car and bus.

Romancing the landscape

Writers, artists, poets, and others have romanticised the district landscape over the decades. The area’s Englishness was first recognised in the 1820s. The district was branded as a ‘Little England’ most famously during the Duchess of York’s 1927 visit when she compared the area to her home.

The valley was popular with writers. In the 1950s, one old timer, an original Burragoranger, Claude N Lee, wrote about the valley in ‘An Old-Timer at Burragorang Look-out’. He wrote:

Yes. this is a good lookout. mate,

What memories it recalls …

For all those miles of water.

Sure he doesn’t care a damn;

He sees the same old valley still,

Through eyes now moist and dim

The lovely fertile valley

That, for years, was home to him.

By the 1980s, the Sydney urban octopus had started to strangle the country town, and some yearned for the old days. They created a country town idyll. In 2007, local singer-songwriter Jessie Fairweather penned ‘Still My Country Home’. She wrote:

When I wake up,

I find myself at ease,

As I walk outside I hear the birds,

They’re singing in the trees.

Any then maybe

Just another day

But to me I can’t have it any other way,

Cause no matter when I roam

I know that Camden’s still my country home.

The end of a district and the birth of a region

The seeds of the destruction of the Camden district were laid as early as the 1940s with the decision to flood the valley with the construction of the Warragamba Dam. The Camden railhead was closed in the early 1960s, and the Hume Highway moved out of the town centre in the early 1970s.

A new regionalism was born in the late 1940s with the creation of the federal electorate of Macarthur, then strengthened by a new regional weekly newspaper, The Macarthur Advertiser, in the 1950s. The government-sponsored and ill-fated Macarthur Growth Centre of the early 1970s aided regional growth and heralded the arrival of Sydney’s rural-urban fringe.

Today Macarthur regionalism is entrenched with government and business branding in an area defined by the Camden, Campbelltown and Wollondilly Local Government Areas. The Camden district has become a distant memory, with remnants dotting the landscape and reminding us of the past.

Updated 14 July 2023. Originally posted 19 February 2018.

Discover more from Camden History Notes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![CoverBook[2]](https://camdenhistorynotes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/coverbook2.jpg)

3 thoughts on “The Camden district, 1840-1973, a field of dreams”

Comments are closed.